The centrepiece of Framework Programme 9 is to be ten moonshot projects that inspire the public and connect people to EU R&D. Researchers are starting to pitch in with their ideas

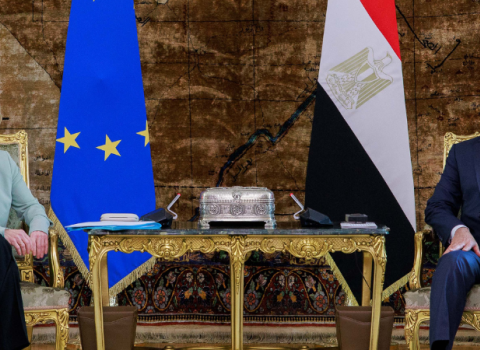

One of the new EU missions should be to improve the speed of diagnosis for dementia, said Michael Arthur, president and provost of University College London, at a Science|Business conference last week. Photo credit: Lysiane Pons

A plan to include up to 10 new research moonshots in the next EU science programme has started a scramble to promote several huge science goals, with three researchers out of the blocks last week at a Science|Business conference, pitching research missions on dementia, obesity and a digital ocean.

The word moonshot comes from the speech by US president John F. Kennedy’s in 1961, in which he called for a space programme that could send a man to the moon and return him safely — a goal that was achieved eight years later.

EU Research Commissioner Carlos Moedas intends to adopt the moonshot metaphor as a centrepiece of Framework Programme Nine, which starts in 2021.

The public needs to hear something stirring and feel inspired, Moedas said. “We don’t feel the same sense of purpose as we did in the past. We say we will invest more in materials or in renewables but people in the street don’t understand much of that. If I talked to my mother or my grandmother about mapping the brain, they will wonder why. People will connect more with a goal, such as creating an all-electric plane,” Moedas told delegates.

Examples of big research missions that FP9 could take on were presented recently in a report by former EU trade Commissioner and former head of the World Trade Organization, Pascal Lamy.

These include achieving a plastic litter-free Europe by 2030; understanding the brain by 2030; producing steel with zero carbon in Europe by 2030; and ensuring the survival of three out of four cancer patients by 2034.

The Commission will launch a public consultation soon to drum up similarly ambitious, far-off ideas. “We have to have something like 10 missions, where we achieve two or three that are great,” Moedas said.

Failure is still useful

The moonshots will instil a sense of urgency and spur big advances into seemingly impossible problems, Moedas said.

One model would be president Richard Nixon’s “war on cancer” in 1971. Forty-six years later, the fight continues, although cancer death rates have declined and there has been long-term success in treating some types of cancer, including lymphomas and testicular cancer. In 2016, the US announced a renewed effort to beat cancer, with a budget close to $1 billion.

“We can have a mission that never achieves its goal,” said Moedas. “When Nixon came with the idea of curing cancer, he never did. But his moonshot had a big impact on treatment for AIDS. So, some big missions won’t get to the place we wanted in the first place, but that’s okay.”

The focus on moonshots is also intended to keep the spotlight on EU science. Feathers were ruffled in Brussels earlier this year when the discovery by NASA of seven new planets beyond the solar system gave no prominent mention to the man behind the breakthrough, Belgian scientist Michaël Gillon, and the European Research Council money backing him.

Moonshots – not for everyone

The moonshot idea is not without its sceptics. The Apollo mission had a singular, measurable goal, but it would be a misleading notion to expect a single cure for a devilishly complicated disease like cancer. Just because we got to the moon doesn’t mean all hard things become easier with a moonshot vision behind them, scientists say.

The same critics point to the challenge of maintaining political commitment to tackling extraordinary problems. Every seven years, the EU research programme gets a re-write by new political masters: keeping everyone focused on old pledges is no easy task. Then again, research officials in some member countries, notably Germany, are sceptical of the Commission getting the power to pick the missions. And, other critics note, the whole idea of a moonshot mission simply doesn’t fit a lot of the R&D that the EU funds, such as industrial research; no way, they argue, the technology for factory robots or supply-chain management could be made to look like an inspiring, Apollo-style mission.

A cure for dementia

Michael Arthur, president and provost of University College London, said one of the new EU missions should be to improve the speed of diagnosis for dementia. “Eradication is something that is almost impossible to achieve. It’s more than a moonshot, it’s a Mars-shot, but we can make a small dent in the universe by identifying it earlier and slowing it down,” he said.

Advanced imaging could pick up changes in the brain before symptoms present themselves, Arthur said. Promising candidate drugs could be assessed in the earlier stages, and new video games could test for early signs of the disease. “If we can delay symptoms by five years, you will halve suffering and care costs,”” Arthur said.

Reducing obesity

A mission on obesity would reward straightforward prevention programmes, and the social science needed to implement them correctly, said Karin Dahlman-Wright, pro vice-chancellor with Karolinska Institute. “I would like to reduce obesity by 90 per cent – not 100 per cent, because I know this is unrealistic,” she said.

A study published this year by the World Health Organisation shows obesity rising among teenagers across Europe. Excess weight drastically increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes.

The WHO estimates that adolescents spend 60 per cent of their time sitting down. “We need to make sure kids get exercise, instead of sitting with their phones all the time,” said Dahlman-Wright. “One of the best inventions last year was Pokemon Go, which made people move more.”

“We need to make sport available and adapt cities so they provide more incentives for walking,” she added. “We have to make sure new tech reaches everyone. If it only reaches a small part of society, it’s no good.”

Fitting oceans with high-speed internet

The most high-tech recommendation came from Lisandro Benedetti-Cecchi, vice rector for European and international research and professor of ecology with the University of Pisa.

He talked about a place where the internet, Wi-Fi, and GPS do not exist: the ocean. “We need to bring the same techniques that have changed our lives on land to the sea. Let’s have wi:fi down there,” he said.

One way to do this is with fibre optic cable or copper wires: but perhaps scientists can come up with novel ways to communicate with submarines, robots, and other underwater instruments?

Our knowledge of the sea would improve with high-speed internet, Benedetti-Cecchi said. “We have better maps of Mars than of sea floors. We spend more money to understand life in space than life under the ocean,” he said.

A new ocean mission could also inspire a new generation of explorers. “We need many new Jacques Cousteaus,” said Benedetti-Cecchi.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.