Commission will begin ‘exploratory’ discussions with Cairo about joining the research programme, despite mounting international concerns about academic freedom

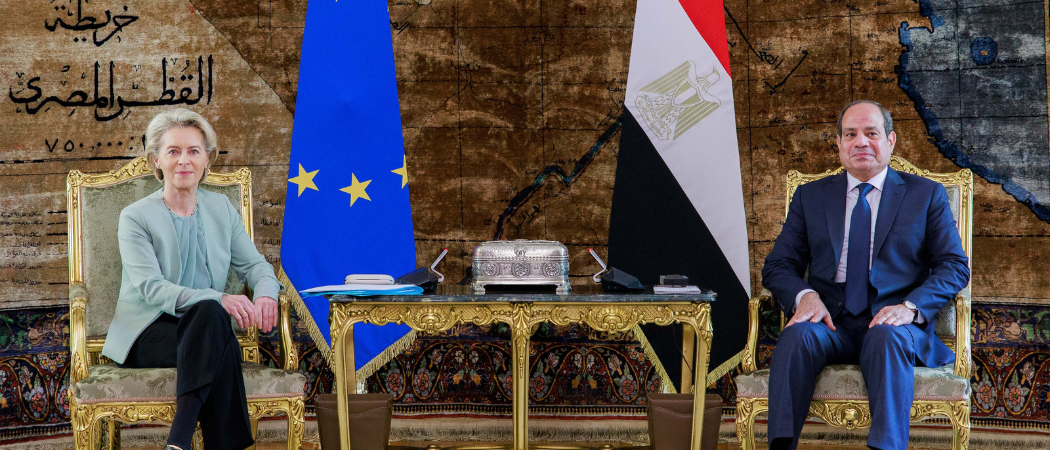

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, on the right, and Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission. Photo credits: Christophe Licoppe / European Union

A European Commission decision to consider admitting Egypt to its Horizon Europe research programme is stirring concern over the country’s poor record on academic freedom – and prompting calls for the Commission to write safeguards into any deal that results.

The news of Horizon talks was included in an EU announcement on March 17th of a broad, €7.4 billion aid package to Egypt intended partly to stem illegal immigration and boost security. As part of the deal, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said, “Egypt can now negotiate its accession to other EU programmes such as Creative Europe and Horizon Europe.” Horizon is the EU’s main R&D programme with a €95.5 billion budget, and Creative Europe is a €2.4 billion cultural diversity programme.

Commission officials insisted the aid and programme access wasn’t part of a quid pro quo to buy Egypt’s help on migration and anti-terrorism – but the country’s history of limiting academic freedom immediately provoked concerns about the message Horizon admission might send on human rights.

Egypt’s record on academic freedom “will need to be improved” if it’s part of Horizon, warned James Moran, former EU ambassador to Cairo and currently an associate senior fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies. While Egypt’s research community could be helpful in Horizon, “It will be important to ensure that any association agreement includes a watertight commitment to freedom of thought and movement of researchers.”

‘Recital 72’ for freedom

Likewise, Christian Ehler, a German member of the European Parliament and longtime rapporteur on Horizon, said, “It should be clear in the negotiation directives that the current state of academic freedom in Egypt is not acceptable. It would put a significant burden on the Commission to ensure that recital 72 is fully respected and that Egypt has to show improvements on academic freedom if it wants to join the Framework Programme."

Recital 72 is a section of the Horizon Europe law that says, “In order to guarantee scientific excellence, and in line with Article 13 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, the respect of academic freedom should be promoted in all countries benefiting from its funds.” A Parliamentary committee on science and technology policy that Ehler chairs just last month published a report on the issue, calling for stricter adherence.

Indeed, EU concerns about academic freedom in Egypt had long held up Horizon membership – as had uncertainty about how to pay for it. In 2014, Egypt lost its eligibility for research aid under standard Horizon funding rules. But since the war in Gaza began, more foreign cash has been flowing to Egypt, especially from the United Arab Emirates.

‘Exploratory talks’

With financial issues apparently resolved, on March 16th, Commission officials said, Egypt’s science and higher education minister wrote to EU research Commissioner Iliana Ivanova formally requesting the start of “exploratory talks” on joining Horizon. Von der Leyen’s announcement followed immediately. It was unclear how long the association talks might take under Horizon law providing a path to membership for countries in the EU “neighbourhood”.

The episode highlights the way Horizon has become a frequent soft-diplomacy tool for the EU – albeit with some weaknesses. There are now 18 non-EU countries that have formally joined Horizon, which means their researchers can compete on equal footing with EU researchers for Horizon grants – and Canada, Korea, Switzerland and possibly Japan are now in various stages of joining, as well. But the EU’s warm welcome of Tunisia into the programme after the 2011 Arab Spring has since turned frosty, with the return of authoritarian government in Tunis. And negotiations for Morocco to join have stalled indefinitely over that country’s border dispute with Algeria.

In the case of Egypt, at issue is the rising police and authoritarian system that Abdel Fattah el-Sisi imposed after becoming president in 2014. Many university faculty and students were supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood government that preceded him; and since then he has been cracking down on dissent, with academics a special object of suspicion. In recent years, the government has given itself the power to hire and fire public university presidents, and grant or deny authorisation for research projects, media appearances and foreign postings of academics. To escape, many prominent Egyptian researchers have left the country – often to wealthy Gulf states that are expanding their own science infrastructure.

Prison and torture

By now, Egypt ranks near the bottom of an annual index of academic freedom maintained by Germany’s Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg and partners. In its latest report, it scored Egypt in the bottom 10% of 179 countries - alongside the likes of Cuba, Turkey and Afghanistan – on five measures of academic freedom.

There’s also a growing dossier of alleged rights violations by Egyptian authorities when dealing with researchers. The best known case is of a 28-year-old Cambridge University PhD candidate, Giulio Regeni, who was visiting Egypt for his research on labour unions. His body, mutilated and showing extensive signs of torture, was found on the side of a Cairo-Alexandria highway in 2016. Egyptian police blamed a criminal gang and dropped further investigation, but Italian prosecutors charged four Egyptian national security officials with murder. A trial in absentia is underway now in Rome.

And there are other cases. In 2020, Patrick Zaki, an Egyptian studying for a master’s degree on gender studies at the University of Bologna, was arrested on a visit home and charged with spreading false information, apparently in an article about his experience as a Coptic Christian in Egypt. According to the Scholars at Risk human-rights group, he was released only last year after an international campaign on his behalf. And in 2021, a Cairo University journalism professor was imprisoned for two months for publicly criticising some Egyptian media and government leaders.

Strong R&D system

Despite all this, Egypt still has one of the strongest research communities in the Middle East. According to UNESCO, Egypt has the second-highest volume of patents and scientific publications in the Arab world, after Saudi Arabia. Health and chemistry are among its strongest fields. Its most-frequent scientific collaborators, aside from Saudi, are American, German, Chinese and British.

It also has among the biggest R&D budgets in the Arab world, at 0.72% of gross domestic product in 2018, according to UNESCO – well below the global average of 1.79%, but still much higher than its neighbours. And to spend that money, the el-Sisi government has rolled out a series of ambitious national plans for science and technology development.

Egypt used to participate regularly in EU research programmes, when it was classified as a developing country eligible for EU research aid. But that changed in 2014, and since then its involvement has plummeted for lack of funds. Since Horizon Europe began in 2021, Egyptian researchers have won just €2.3 million in grants – partly under a massive science diplomacy project called PRIMA, in which the EU is supporting Mediterranean Horizon members and non-members for agricultural and water R&D. The single biggest Egyptian recipient is its Agricultural Research Centre, according to the Commission’s Horizon database.

Egyptian researchers cheered the Horizon news. For Egypt’s universities, it will be “really important,” said Ali Abdelaziz Ali, a food sciences professor and former vice president at Cairo’s Ain Shams University. “Research needs such funds to get motivated, to get better results, to get more equipment that can match what’s going on in the world” of science outside Egypt. But he disputed claims of excessive government controls over research. “Academic freedom is good, and we don’t have any restrictions.” While there is at his university an ethical review committee for research plans involving animals or humans, “no one can tell me to do this, or not to do this. I am the one who makes my strategic research plan.”

Still, the academic freedom issue may prove important in what comes next. David Wheeler, a former editor of Egyptian-led academic news service Al-Fanar Media, said the EU supporting individual Egyptian researchers is understandable. But “creating a government-to-government arrangement as it seems the EU is considering would put an implicit stamp of approval on the authoritarian Egyptian leadership. The Egyptian government permits little if any opposition, has detained a great many academics whose opinions or activities it did not care for, and restricted many academics' movements with travel bans."

Editor’s Note: This story was corrected 22 March to reflect the status of Al-Fanar Media as Egyptian-led.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.