A drop in government share of global R&D spending sparks alarm – even as political anxiety over the future of technology rises. More than 40 per cent of global R&D is now performed by just 200 companies

Source: OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2018

Is government dead? Not quite – but OECD analysts warn that the ability of governments to influence how technology develops may be weakening.

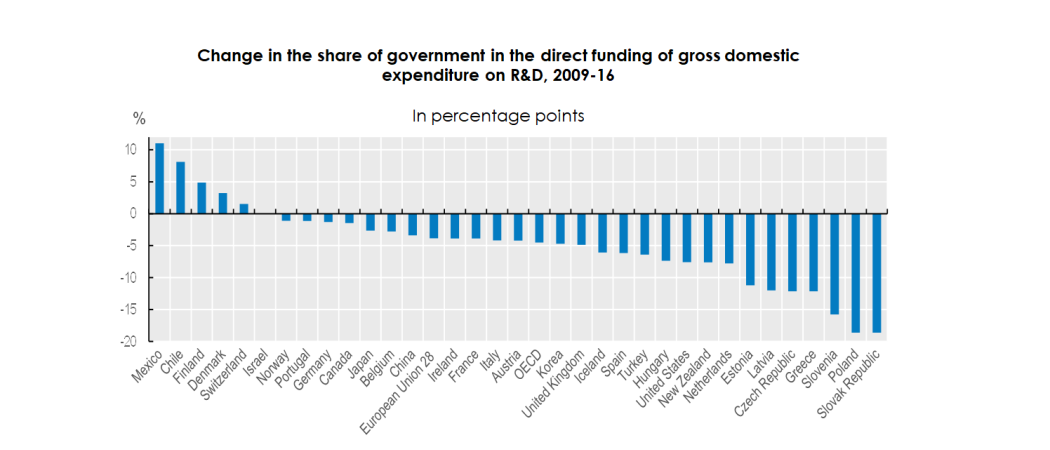

At a Brussels briefing 20 February, representatives of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development said the government share of GDP dedicated to R&D spending across the developed world dropped by four percentage points from 2009 to 2016, from 31 per cent to 27 per cent.

At the same time, staffing in some government ministries has “hollowed out” and more emphasis is going towards indirect action such as tax breaks and partnerships, rather than direct government grants.

As a result, “Government is not always the biggest player it used to be in the (R&D) system,” said OECD senior analyst, Michael Keenan.

The conclusion is contentious – and indeed, at the briefing it was immediately contested by some national and European Commission officials. But the data fit into a growing feeling among science and technology policy makers that they are less in control of technology than in the past.

One manifestation of that, the OECD officials said, is the current political anxiety about Facebook and other big tech companies – many of which wield bigger R&D budgets than do most governments, and which are able to push technologies such as driverless cars into new directions that aren’t yet regulated.

International data tracked by OECD shows 42 per cent of global R&D is performed by just 200 multinational companies – and in computing and communications, the top 200 firms file 51 per cent of all the patents.

These trends coincide, said Keenan, with “a major shift” over the past 10 to 15 years in governments supporting R&D through broad business tax breaks, rather than grants. While tax credits encourage investment in R&D, economists say they don’t usually push spending towards any particular policy goal, such as climate mitigation. “They provide little leeway for governments to influence the direction of spending,” Keenan said.

On the other hand…

Of course, not everybody sees a problem there. For one senior Austrian official at the briefing, a decline in government R&D spending actually reflects a rise in business spending – and that’s “healthy” rather than harmful. In Austria, over the past decade, the corporate share of national R&D spending has risen from 60 to 66 per cent, simply because, even as Austria’s national R&D budget has risen, business spending has risen even faster.

While that’s true in Austria, in many other developed countries the actual amount of government spending, rather than just the percentage, has yet to recover from the 2008 crash, according to the OECD analysts.

At the same time, some new developments could help governments keep in the game. One example is adopting digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, to monitor what business is doing with its R&D money, or to spot emerging technologies and trends faster. Another is to foster more international cooperation in science and technology, to coordinate public spending in shared global goals such as slowing climate change.

Indeed, OECD noted, governments in general seem to be more interested than ever in steering technology – to push their economies towards sustainable development, better health care or other “missions.” The paradox is this policy push comes even as the share of government spending is dropping. That, “is not absolutely a bad thing”, said Dominique Guellec, head of the OECD’s science and technology division, but “it could affect the efficiency” of those governments trying to steer technology.

When gauging government influence on technology, “it matters how much money” it has to spend on research, Guellec said. “Being rich doesn’t make you happy, but it helps.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.