The world’s largest radio telescope will have CERN-like structure to smooth its funding outlook

Countries involved in the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project to build the world’s largest radio telescope this week established a global governing body to oversee the many political, bureaucratic, academic and scientific hoops it will need to leap through before construction is completed.

Australia, China, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa and the UK signed an intergovernmental deal at a ceremony in Italy on Tuesday to establish the SKA Observatory. The new body, which will be similar to other international science structures such as CERN, will replace the SKA Organisation, which has managed the telescope’s design and construction activities since 2012.

The observatory, to be headquartered at Manchester University’s Centre for Astrophysics at Jodrell Bank, will award contracts for SKA’s construction. The UK is investing £100 million in SKA, 16 per cent of the total construction cost.

“The treaty shows the commitment of our partners to the project. But the other reason [for the treaty] is stability, to ensure it survives and is not subject to annual spending reviews,” said Alistair McPherson, deputy director general of the SKA Organisation.

Signatories must now ratify the convention in their parliaments, which could take up to a year. Sweden and India are also expected to sign up as full members.

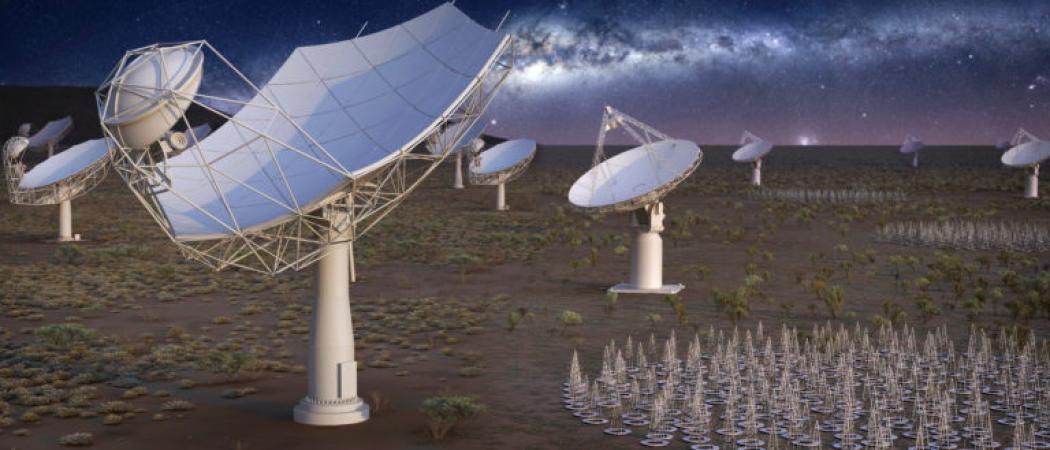

When complete, sometime around 2030, SKA will be the largest radio telescope ever built, and 50 times more sensitive than current instruments. It will consist of around 2,000 radio dishes in Africa, together with up to one million antennas in Western Australia that will collectively cover a square kilometre.

The telescope’s main scientific work will be gathering data on a wide range of physical phenomena in space including galaxies, black holes and dark matter.

“SKA cuts right across the field of physics, from cosmology to the fundamental physics of gravitational waves. It’s a pure science machine that will help us answer so many questions,” said McPherson.

The hope for many is that the project will pick up echoes of extra-terrestrial life. SKA leaders say the sensitivity of the project’s many listening devices will enable it to hear the equivalent of an airport radar system on distant planets.

The antennas and dishes are being erected in vast open spaces, far from any large cities, giving scientists an unobstructed view of the sky.

The SKA’s 346,000-hectare Australian site in Boolardy is a place “with many more sheep than people”, McPherson said.

The project has purchased some 130,000 hectares of land in South Africa’s Karoo region belonging to 36 sprawling farms, rearing sheep, ostrich and springbok.

“Many of us have not had reason to travel to this community before,” said South African science and technology minister, Mmamoloko Kubayi-Ngubane. “But you should see the life that has been injected into the region. It goes beyond astronomy; I found researchers who were there to study the environment, for example.”

Foreign investment in South Africa is up because of the project, she added. But there’s also the smaller impacts it’s having. “We’ve built a road into the region which will benefit the whole community,” Kubayi-Ngubane said.

The build-up is gradual, with the first phase of construction comprising 194 dishes in South Africa and around 130,000 antennas in Australia, costing €674 million.

A testbed of antennas, called the MeerKAT, has already picked up the radio glow of some 1,300 distant galaxies. “The number of papers from the first images will keep us going an awfully long time,” said McPherson.

Astronomers estimate that SKA will eventually generate 35,000-DVDs-worth of data every second, or a new World Wide Web’s worth of data every day. SKA leaders are currently looking for sites to build supercomputer centres to house the data.

“It will dwarf anything that Facebook and Google can throw at us”, said Mark Thompson, dean and professor of astrophysics at the University of Hertfordshire.

Thompson is one of the leaders of a joint UK-South African project called DARA, which is training students in eight African countries to take advantage of the SKA. He organises astronomy workshops across the continent and says, “It would be a crime if all this equipment was to be just operated by expats.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.