Alternative for Germany’s wins in the general election could further fuel funding wars in Brussels, as EU hurries to set its next long-term budget. The prospect of securing more funding for research is dimmed

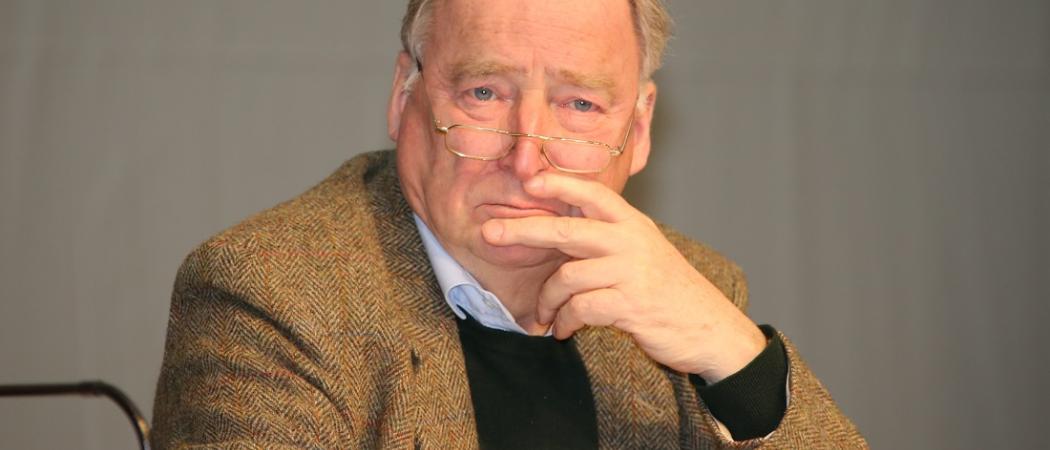

Alexander Gauland, the new leader of Alternative for Germany. Photo: blu-news.org

The entry of a far-right party into Germany’s Parliament for the first time in more than 60 years promises to further complicate difficult EU budget talks- and possibly to limit EU ambitions - if Alternative for Germany (AfD) lives up to its manifesto pledge to stand against uncontrolled spending in Brussels.

The result will complicate the push to boost investment in research and innovation from about 8 per cent of the EU budget today, and raises the prospect that the EU could reach 2021 without an agreement on the next budget cycle, according to speakers at a conference on the future EU budget on Monday.

“We have to invest more in innovation, it’s as simple as that,” said Commissioner for digital society Mariya Gabriel. EU money can jump-start next-generation 5G networks, Gabriel said. “We missed the boat with 2G, 3G and 4G. Let’s not lose opportunities on 5G.”

Former World Trade Organisation head and former EU trade commissioner Pascal Lamy, who recently authored a report that called for the next EU budget cycle to double spending on research and innovation, made a similar appeal.

“The future of Europe rests on our brainpower,” he said. “But our science production is on the decrease; our market share is being eroded. And things are not good at all in innovation.”

One way to free up money for research would be to abolish EU regional funding to rich member states such as Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands, suggested Daniel Gros, director of Centre for European Policy Studies.

“What if rich countries said, ‘We don’t need regional funds anymore’? What about giving this money to research instead? If you do that, you could easily double research spending, without hurting anyone else,” Gros said.

Filling the Brexit funding gap

The German election result could also limit EU Budget Commissioner Günther Oettinger’s room for manoeuvre. When leaders in Brussels are not worrying about populist parties, the other constant presence in their minds is the big hole in the accounts made by the impending departure of the UK, the second-largest contributor to the EU budget after Germany.

To make up a financing gap of around 16 percent of the EU’s overall budget, or €10 billion to €11 billion annually, “We should consider raising European countries contributions slightly,” Oettinger told the meeting.

Annual EU spend is around €145 billion, or about 1 per cent of the wealth generated by EU economies every year. Oettinger suggested raising EU state contributions from 1 percent to 1.2 per cent of gross national income.

“We can go beyond the magical number of one per cent,” agreed Ana Paula Zacarias, secretary of state for European Affairs of Portugal.

However, there are signs that Oettinger’s proposal will be excruciatingly difficult to sell to member states, where parties such as AfD will be guarding against attempts to siphon off revenue sources they feel should flow to member governments.

Brussels should be “Looking at new resources, and not reaching into anyone’s pockets,” said Mateusz Morawiecki, deputy prime minister of Poland.

For new streams of revenue, the EU should pursue the politically thorny path of setting a tax on financial transactions in Europe and extracting more tax from technology companies, Morawiecki said, pointing to a Commission study last week which found the likes of Google, Facebook and Amazon pay less than half the tax of traditional high street companies in Europe.

“These huge companies are not taxed [enough] and our GDP is losing out because of this, the EU budget is losing out because of this,” said Morawiecki. “We could have a bigger pie.”

Bring down your expectations

With a deadline for a draft budget in May 2018, and no clarity about what relationship the UK might have with the EU after its departure, there are few good choices for the Commission, and nobody should expect a bigger EU budget, said Alexander Stubbs, former Finnish finance minister. “Bring down your expectations. The EU budget is not going to grow. There is simply no possibility,” he said.

The political sands will continue to shift in Brussels, regardless of the shape of the coalition in Germany or fallout from Brexit. Parliamentary elections are scheduled for May 2019, with a new Commission taking office the following November. That means any proposals developed now may be subject to major revision during 2019 and 2020.

Financial schemes hard to scrutinise

There were also appeals to simplify the EU budget. It has become harder to scrutinise, said Jean Arthuis, chair of the budget committee at the European Parliament. “You have all kinds of jiggery-pokery with new financial instruments,” Arthuis said, referring to the European Fund for Strategic Investments, also known as the Juncker Plan.

“Guarantee schemes are fine at the beginning but after a few years, some projects may be in trouble, and then you have to fork out,” he said. “It’s all a bit of a headache for the European Parliament. It’s beginning to slip through our fingers.”

Kill the seven-year budget

It is increasingly difficult to keep an overview of everything, agreed Klaus-Heiner Lehne, President of the European Court of Auditors, the EU financial watchdog.

He urged the EU to reform its long-term financial planning. “Seven-year detailed planning is no longer sensible. It clearly doesn’t work,” he said. “When things crop up, the Commission’s solution is to create new instruments. Then you get more and more parallel structures which are less transparent.”

German election adds to Brexit budget pressures

After winning 94 seats in Sunday’s election, the Alternative for Germany gained a powerful perch from which to alter the agenda of European politics.

The AfD surge in Germany will complicate life for conservative chancellor Angela Merkel, de facto EU leader, who watched her party slump to its lowest share of the national vote in nearly seven decades, and by extension the path ahead for Brussels, where leaders are hurrying to put together a fiendishly complicated EU seven-year fiscal blueprint.

In its manifesto, which mainly focuses on migration and security, AfD warns against uncontrolled spending in Brussels. “Merkel may now feel pressure from both the AfD and the Eurosceptic wing of her party to move away from federalist proposals,” Stijn van Kessel, lecturer in European politics at Queen Mary University of London told Science|Business. “So domestic politics may limit her freedom to act at the European level, and also hamper a potential push for further European integration.”

German politics will be in a state of uncertainty until a new government is formed, which might not happen until 2018, Cas Mudde, a Dutch researcher at the Centre for Research on Extremism at the University of Oslo told Science|Business.

Merkel will now probably have to form a coalition with the liberal Free Democrats and the Greens. “If it is that the German people want stricter borders, Merkel’s party will move to the right, and Merkel will have less space to push for more EU integration,” Mudde said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.