Three years after the attack on Ukraine, positions are changing, but there is no more money in Germany for military research

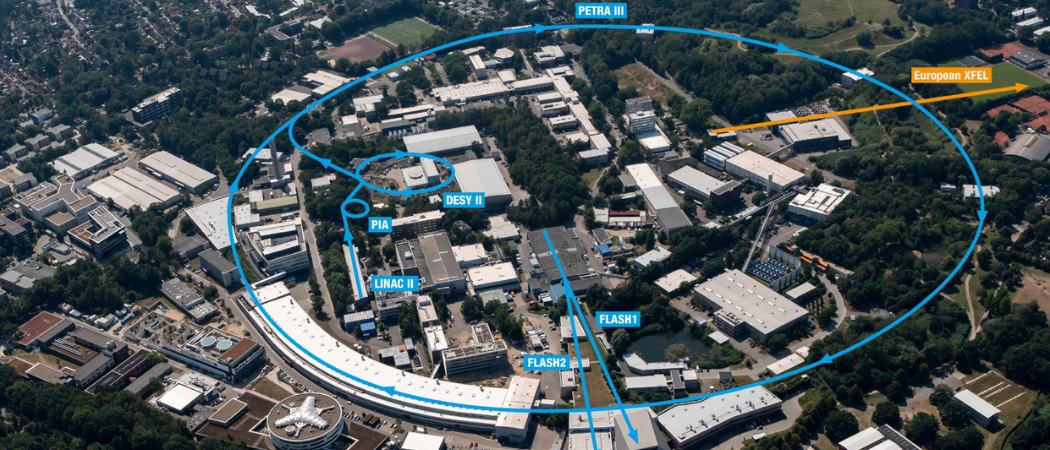

The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) research centre. Photo credits: DESY

Science|Business - Table.Media partnershipScience|Business has partnered with Table.Media, a leading source of news about higher education and research in Germany. Each week, we are publishing one of each other’s stories to give readers an even broader range of insight into R&D policy across Europe. |

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, security and defence research has been increasingly discussed in the German scientific community. The first results are now visible, but change is still slow.

The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) research centre, for example, wants to revise its restrictive stance, and civil clauses that prohibit work on military-related projects are being questioned at universities.

However, according to the Fraunhofer Society, a network of applied research centres, there has not yet been a tangible increase in budgets. “It is up to politicians to provide the necessary money for research and technology in the defence budget,” said Jürgen Beyerer, chairman of the Fraunhofer Segment for Defence and Security, in an interview with Table.Briefings. At the very least, the research budget should increase in proportion with the announced increases in defence spending, he said.

Calls for a less pacifist approach are not new. “Peace needs modern defence. That is why the existing civil clauses must be critically revised in terms of peacekeeping research,” said Johann-Dietrich Wörner, president of Acatech, Germany’s National Academy of Science and Engineering, in 2023. Civil clauses are voluntary commitments by scientific institutions to conduct research exclusively for civilian or peaceful purposes.

Currently, 76 universities have a civil clause. A survey by Table.Briefings of some of these universities revealed that the topic is being widely discussed. Chemnitz University of Technology states that the civil clause is to be “adapted in line with the times in the process of amending the basic regulations of Chemnitz University of Technology.” But it is not yet clear when.

Discussions are also taking place at the Technical University of Berlin. At the beginning of 2024, vice president Stephan Völker asked the university’s ethics commission for advice. Following initial discussions in 2024, a concrete position is to be drawn up in 2025.

“The goals [of research] must be peaceful,” responded the Technical University of Darmstadt. But cooperation with the German military, as a defensive force, is not ruled out in principle, the university explained.

Political interventions

State-level interventions by politicians to scrap civil clauses have so far had no results. A new law in Bavaria prohibits civil clauses, but they did not even exist in this form in the state. In Bremen, the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) parliamentary group tabled a motion last year to abolish the civil clause in the state's higher education act. But it was rejected in December with votes against from the Social Democratic Party, Greens and Left Party, according to the CDU.

The situation is somewhat different for non-university research institutions. The German Aerospace Centre (DLR) has been active in the defence and security field for decades. But it distinguishes between civil security research, which is carried out at the Centre for Satellite Based Crisis Information, for example, and defence research. This includes, for example, testing new radar technology for the Eurofighter with Airbus.

“In the changing, intensifying security situation, established cooperation between the armed forces, authorities, stakeholders, research and industry has proven its worth,” said DLR chief executive Anke Kaysser-Pyzalla in an interview with Table.Briefings.

Breaking down barriers

At a time when many technologies are used in both the civilian and military sectors, a more pragmatic approach makes sense. This is how the Fraunhofer Society puts it in a recently published position paper, Defence research in the Zeitenwende,- a term popularised by chancellor Olaf Scholz following the invasion of Ukraine to describe a new geopolitical era.

“Breaking down the barriers between civilian and military research helps to make defence research more efficient and innovations from the civilian sector more quickly usable by the military,” write the authors, which include Beyerer.

Fraunhofer is working on various topics, from quantum sensors that provide precise images of their surroundings to quantum computing that promises revolutionary computing power to optimise decisions on the battlefield.

No new money

In total, Fraunhofer receives around €130 million a year for defence research, said Beyerer. “This has not grown in recent years, despite the Zeitenwende,” he said. In order to maintain technological sovereignty, more equipment is urgently needed. “Defence research today is the defence capability of tomorrow.” In the scientific community, he sees signs that the mood is changing.

However, there are still some critics within institutions, for example at the DESY research centre in Hamburg. To date, no research that could serve military purposes has been permitted at the Petra X-ray source, one of DESY’s facilities. In the summer, the centre’s directorate considered whether this was still appropriate. There was both agreement and opposition among the staff. In opposition, a group called Science4Peace@DESY was founded and called for “the intensification of civilian and peace-building research instead of opening up civilian facilities for military research.”

DESY’s board of directors has sketched an initial plan of how the centre could handle security-related research, but without affecting the core civilian nature of DESY, a spokesperson explained. “An internal working group is currently being set up to identify open questions and take a detailed position,” they said. This will be followed by further consultations, including a town hall meeting in May.

Acatech boss Wörner now wants action from the universities. “So far, research contracts from the Ministry of Defence and the armed forces have mainly gone to institutions such as Fraunhofer and the DLR,” he recently told Handelsblatt. “The universities do make contributions, but they could certainly do a lot more, from AI to quantum and materials research.” This is unlikely to be due to the civil clauses alone. Acatech intends to conduct a study to determine what the specific hurdles are, due to be published in June.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.