Shifting political landscape could cause trouble for big spending programmes like Horizon Europe

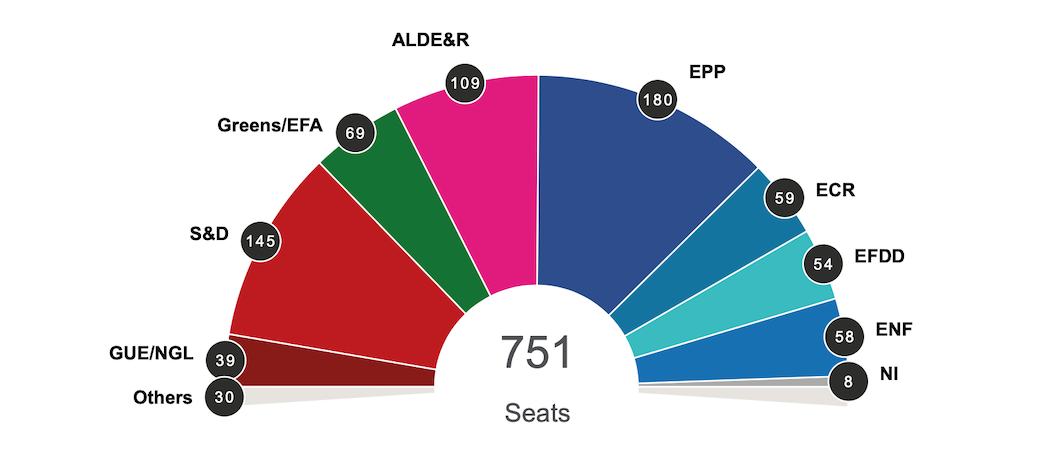

Centrist parties lost seats to Eurosceptics and environmentalists. Image: Results projection from the European Parliament, last updated 15:38 CET, 27 May

Last updated 15:36 CET, 27 May 2019

A surge in voter turnout across most of Europe saw centre-left and centre-right parties lose scores of European Parliament seats to Eurosceptics and environmentalists, but liberals also made major gains.

Manfred Weber, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) candidate for Commission president, lamented on German television as early voting results arrived that the “the middle, the democratic centre, is weakening in Europe.”

That could make it harder to pass big-package legislation, such as the proposed €94.1 billion Horizon Europe R&D programme. A newly-enlarged Eurosceptic group has vowed to push back against what they see as Brussels largesse. At the same time, a surge in Green parties could complicate legislation over the even-bigger Common Agricultural Policy – which French Green leaders, for instance, have pledge to make more eco-friendly.

For the first time in the history of the European Parliament, the combination of the EPP and the centre-left Socialists & Democrats (S&D) is not expected to constitute a majority of MEPs, though they are expected to remain the two largest groups.

The liberal Alliance of Liberals and Democrats (ALDE) group is on track to finish third overall – in part because of the decision of French President Emmanuel Macron to throw his En Marche party’s votes in with other liberals.

The loss of the EPP-S&D majority raises the possibility of a new three-way alliance, but also of new rivalries, and complicates the political geometry for anyone wanting more big-package legislation.

In a European Parliament press conference at midnight on 27 May, Weber appeared to cast doubt on the prospect of an alliance with ALDE and instead hinted at cooperation with the Greens, who will be the fourth-largest group. Weber also ruled out cooperation with "extremists from the left and from the right." On the other hand, Frans Timmermans, the S&D's lead candidate, talked of a possible "progressive alliance" that would exclude the EPP.

ALDE and Emmanuel Macron have been critical of the so-called Spitzenkandidat process, an informal arrangement whereby the lead candidate of the largest political group – in this case, Weber – goes on to become president of the European Commission. The incumbent Jean-Claude Juncker is the only Commission president to be chosen in this way.

But the most significant results may not be in the who’s up-who’s down outcomes – but rather in the sheer numbers who turned out to vote. Since direct voting for MEPs began in 1979, turnout through most of Europe has slowly dropped – to less than a quarter of registered voters in some countries. Turnout is estimated to be 50.94 per cent, the highest in 25 years, as voters on left and right decided to make their opinions known.

Eurosceptics gain strength

The European Conservatives and Reformists group – which is pro-EU but opposes deeper integration – is projected to drop from third to fourth largest group in the Parliament, greatly diminished by the near-wipeout of British Conservative MEPs.

A new alliance of nationalists and Eurosceptics is projected to come fifth, just one seat behind the ECR. Though such groups have thus far been a small minority in the European Parliament, support has grown in many countries for anti-immigration parties since the 2014 election, which took place before the 2015 migration crisis.

Italy's League party, led by deputy premier and interior minister Matteo Salvini, has joined forces with other right-wing groups including Germany's Alternative for Germany party, France’s National Rally, the Finns Party and the Danish People's Party to create the European Alliance for People and Nations. The League topped exit polls in Italy.

A second Eurosceptic alliance led by Nigel Farage, the European Freedom and Direct Democracy Group, is projected to be only a few seats smaller than Salvini's alliance.

An enlarged eurosceptic minority could make its presence felt most strongly in the next legislature, particularly in committees, which have a strong hand in drafting positions for the whole assembly to adopt.

Nigel Farage's Brexit Party came first in the UK by a very wide margin, with an estimated 32 per cent of the vote. Britain's governing Conservatives, meanwhile, are predicted to come fifth, with just nine per cent of the vote, behind the Liberal Democrats on 20 per cent, Labour on 14 per cent, and the Green Party on 12 per cent.

Green wave

The news wasn’t all bad for EU integrationists. In the Netherlands, Eurosceptics in the Forum for Democracy and the Party for Freedom appear to have fared poorly. The pro-EU Labour Party of Frans Timmermans, who hopes to succeed Jean-Claude Juncker as Commission president, is projected to win the most seats.

The Greens are riding a wave of concern over climate change, is projected to receive more than 20 per cent of the vote, putting it in second place behind Angela Merkel's centre-right CDU/CSU. The latter's vote share is projected to have fallen to less than 28 per cent, down from 35 per cent in 2014. The centre-left SPD is projected to have fallen even further, with less than 16 per cent of the vote compared to 27 per cent in 2014.

In Ireland, a swell of votes for the Green Party put it in line to secure two seats, and finish third behind the two main centre parties. The Greens had 52 seats overall in the last EU legislature, making it the fourth biggest political grouping, and are expected now to gain around 10 more of the Parliament's 751 total seats.

ALDE also made gains in Romania with the rise of the new Save Romania Union, and in the UK, where the anti-Brexit Liberal Democrats bounced back after years in the doldrums.

Shifting landscape

The loss of the EPP-S&D majority raises the prospect that the two main groups will be forced to work with shifting majorities from bill to bill, or to form new coalitions with other party groups, such as the green and liberal factions.

Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, will be a key player in the building of any nationalist-populist coalition in the next Parliament. Orbán has spoken of the importance for the future of the continent that “anti-migration” forces dominate the next parliament and has plastered Budapest with anti-migration billboards.

His party, Fidesz, was recently kicked out of the EPP over some of its campaign methods, leaving Orbán mulling whether to go in with Salvini and his new nationalist bloc.

While it is still likely weeks before a new political geography emerges in Brussels, analysts say parties in favour of deepening European integration could still dominate Parliament if the EPP and S&D can cooperate with either the Greens or ALDE, bolstered by new MEPs from Emmanuel Macron’s La Republique en Marche.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.