Since the 2000s, the EU has been pooling resources to procure bigger machines. With two top 10 computers set to start operations this year, the strategy is beginning to bear fruit

Oakridge machine. Photo : Flickr / OLCF at ORNL

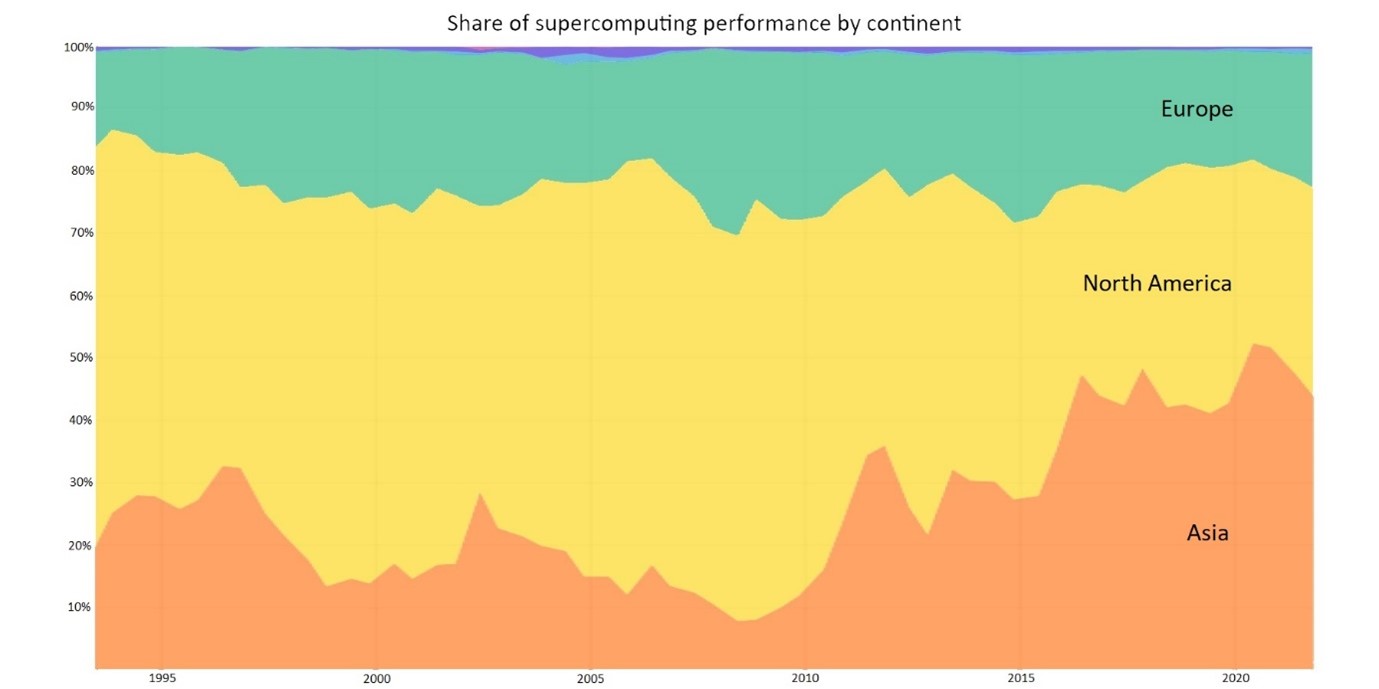

Europe has managed to hold its own in the race to build the world’s most powerful supercomputers, maintaining a constant share of global performance despite the emergence of China as a supercomputing giant, according to a Science|Business analysis of nearly three decades of data.

A decade after the Commission launched a strategy to pool the EU’s supercomputing resources, it appears it has worked to an extent, keeping Europe in the game in the face of intense Chinese competition.

“Europe has had quite a good performance,” said Thomas Lippert, head of the Jülich Supercomputing Centre in Germany, which is hoping to host the EU’s first machine capable of one billion billion operations per second.

“I would be much more worried in North America,” he added, pointing to the US’ dwindling share of the world’s supercomputing power. The relative decline is despite the fact that the US is home to five of the current top ten most powerful supercomputers in the world.

With researchers hungry for ever more power to model everything from the climate to cancer treatments, supercomputers are crucial to preserving the EU’s scientific and industrial edge.

A few months after the pandemic hit, for example, supercomputers were fired up to screen 500 billion known molecules to identify potential candidate drugs. Supercomputing did in weeks what would previously have taken decades, the Commission claimed.

A Science|Business analysis of data from the Top500, the twice-yearly updated list of the world’s fastest machines, shows that in terms of combined performance, Europe has held steady just as the US share has been squeezed by China.

When the list began in 1993, the US was the world’s supercomputing hegemon, with 62% of the globe’s supercomputing power. Japan had just under a fifth, and Europe 15%. Mainland China did not have a single computer in the list.

Since then China’s supercomputing prowess has exploded, particularly in the last decade. It now has more computers in the Top500 than the US, although on measures of combined performance still lags slightly behind Japan.

It is now a much bigger pie, but from 1993 - 2021, the US share of performance has almost halved, and stands at 32.5%.

In contrast to American decline, though, Europe has managed to hold and even slightly improve its share, which is now 21.5%.

“Relatively speaking, the US has fallen back, but Europe not so,” said Janne Ignatius, council chair of the Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe (PRACE).

Pooling resources

At least in part, this is because of a concerted effort to combine European resources to afford bigger and better machines.

European efforts to link up its supercomputing strength go back at least to the mid-2000s, when the HPCEUR strategy, between the Commission, member states and industry, set about creating new computing centres across the continent. By contrast, the US only launched its own national strategy in 2015.

2010 saw the creation of PRACE, which allowed researchers across Europe to access seven new supercomputers located in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland.

These machines were still funded with national money, but Brussels put in €125 million for other things like training, coordination of the network, and international collaboration, and the project applied pressure on national governments to be more ambitious when tendering for new computers, argues Ignatius.

In February 2012, the Commission launched a fresh push to step up Europe’s computing power, and its capacity to manufacture the fastest machines.

It warned that Europe spent just half of the US on supercomputers. Both Japan and the US had more capacity that all member states combined. What’s more, US manufacturers dominated the European market. This attention from Brussels is one of the reasons why Europe has held its own in the past decade, Ignatius believes.

Then in 2018 came an initiative that Ignatius says “changed drastically” the whole approach to supercomputing in Europe, the European High Performance Computing Joint Undertaking, or EuroHPC for short.

Crucially, member states, the Commission, and industry pool their money – a total of around €7 billion in the period 2021-27 – to afford the very best machines.

“Instead of having different EU countries procuring the same (or nearly the same) small HPC systems, the EU will have a number world-leading supercomputers deployed across its territory,” said Anders Jensen, EuroHPC’s executive director.

So far, the consortium has put four machines into operation, in Luxembourg, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria, that have entered the Top500.

That’s not to say national governments aren’t still investing themselves. “In the last two years, quite a few big machines have come online in Germany,” noted Lippert.

But the real heavyweights are yet to power up. This year, at least two EuroHPC so-called “pre-exascale” machines in Finland and Italy should start operation, and possibly a third one in Spain. They should all be among the five-to-ten fastest in the world, says Ignatius.

“With such machines, the EU will be back in the global computing landscape, as the procured systems will bring the European supercomputing capacity in par with those of China and US,” says EuroHPC’s Jensen.

The next frontier will be exascale computers capable of performing one billion billion operations per second, and with a level of power equivalent to all the smartphones in the EU, estimates the Commission.

Powering ahead

Last month, EuroHPC put out a tender to build Europe’s first exascale machine. Jülich will be one of the sites in contention, and Lippert wants it online before the end of 2023.

But by some measures, Japan has already beaten the EU to exascale with its Fugaku computer, currently ranked as the fastest in the world and three times more powerful than the current number two at the US Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

Oak Ridge will soon be upgrading, with its Frontier exascale computer due to enter operation this year. And China is believed to already have two exascale machines, although has so far kept them relatively quiet, not yet submitting performance data to the Top500.

Yet the race for supercomputing dominance isn’t just a matter of building the most powerful machines. Not all research problems need gargantuan amounts of processing power. And some mid-range machines have a computing architecture specifically tweaked to tackle, say, climate modelling, or cybersecurity.

EuroHPC’s procurement drive hasn’t been entirely plain sailing. A tender for a massive new system based in Barcelona, called MareNostrum 5, was cancelled last May after the Commission and member states failed to get “the needed majority to reach an agreement to adopt the selected tender,” according to consortium documents. In December EuroHPC restarted the €151 million tendering process.

In another example, Lenovo launched a case against EuroHPC after it lost out to France's Atos in a fight to build an Italian supercomputer called Leonardo.

In its claim, Lenovo says that EuroHPC used an award criterion of “EU added value”, but this was “unrelated to the subject matter of the contract, and breached the principle of equal treatment”. The EuroHPC spokeswomen said it does not comment on ongoing legal proceedings.

This touches on a dilemma as the EU builds up its supercomputing muscle: buy local to strengthen its own capacities, or open up to US, Japanese and Chinese vendors to get the best price?

“Europe is the most open market place in the world, in high performance computing in particular, and this is not always reciprocal,” said Jean-Philippe Nominé, vice chair of the European Technology Platform for High Performance Computing, an industry-led think tank.

Subsidies given to non-EU rivals “make it quite difficult to compete fairly,” he said, speaking in a personal capacity.

Still, Atos, by some way the Europe’s most successful supercomputer manufacturer, has been gaining market share. It makes 8% of the world’s Top500 computers, compared to 3% a decade ago. Until 2019 Atos was led by Thierry Breton, now internal market commissioner and one of Brussel’s most forceful advocates for EU technological independence.

Over the same period, Chinese makers have comprehensively overtaken US rivals. Lenovo, which built its business around the acquisitions of IBM’s personal computer division and servers business, is now the most prolific vendor in the world, accounting for more than a third of the Top500 systems.

“The ideal situation is that European vendors are so globally competitive that they win the bids,” said Ignatius. “That’s happening quite frequently. I have seen an increase in the number of won bids, particularly from Atos, in recent years.”

“I don’t think that Europe has to fear anything if Europe goes for an open procurement,” said Lippert. “Because European companies are good enough to succeed.”

As for EuroHPC, it has shopped around: some systems have been bought from Atos, some from HP, and one from Fujitsu. The development of EU-based supercomputing technologies is an “important goal” of the consortium, says Jensen.

Although the EU has kept pace with the rest of the world, Jensen is far from triumphant.

“Europe has lagged behind North America and Asia in the past 30 years, steadily contributing with 15-20% of the Top500 systems and slightly less for the overall performance count,” he said, and this is disproportionately low given how much research using supercomputers takes place in the EU.

The picture is even worse if you look at the top ten systems, he continued – Europe has never hosted the fastest computer in the world.

But now, he said, the effort to “restore Europe’s position as a leading high performance computing power globally” is on in earnest.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.