The east-west innovation divide is now front and centre in EU innovation policy. This pleases the movers and shakers in central and eastern states, but also raises their expectations for action

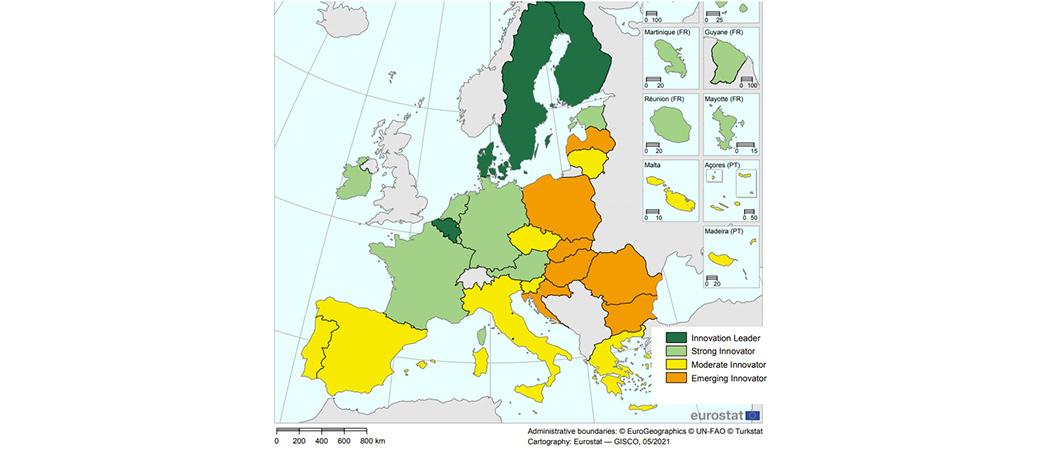

The performance of innovation systems varies across Europe. Source: European Innovation Scoreboard 2021

The Commission’s Innovation Agenda, adopted last week, has been welcomed in central and eastern Europe for its high-profile acknowledgement of the innovation divide within Europe, and for nailing down the EU’s most urgent innovation challenges.

But there are also gaps to be filled, concerns about the agenda’s focus, and the thorny question of how this ambitious policy will be implemented.

“Until now, the question of the innovation divide has never been emphasised so highly,” said Tadas Tumėnas, head of the Lithuanian Research Development and Innovation Liaison Office in Brussels. “Everyone talked about it, but officially it was not acknowledged. Now we have this communication, you can see that the Commission sees it as a problem.”

“It’s important that the EU has opened up this issue,” said Matej Rus, head of Start:up Slovenia, chief executive of Venture Factory, the business incubator of the University of Maribor, and head of its Innovum innovation platform. “The agenda is clear, it’s written down, and that means national governments and regional authorities can read it. Without a clear message like that, nothing happens.”

For example, the start-up community in Slovenia has been lobbying unsuccessfully for the government to introduce special treatment for business angel investments and other support measures to boost private investment in start-ups and scale-ups. “Having this in the agenda could help us discuss these measures with our ministries.”

There is also a perception that the agenda makes a strong case for tacking the innovation divide. “When you look at a list of widening countries, that is 15 out 27 member states - a majority - are underperforming. The agenda talks about building a true pan-European innovation ecosystem, so you can see how important bridging this innovation divide will be,” said Joanna Kubiak, senior policy officer in the Wielkopolska Region Brussels Office, and a member of the task force on widening and deepening engagement set up by the European Regions Research and Innovation Network.

The agenda is broadly praised for identifying the most important challenges and bottlenecks for innovation in Europe, and for attempting to connect up the various funding schemes available. Establishing a link between cohesion and innovation funding is particularly valued. “It’s good to have a strategy that connects everything,” said Kubiak.

And in general, actors from the region think the agenda’s five major objectives of helping companies scale up; enabling experimentation and public procurement; strengthening innovation ecosystems; fostering talent; and improving policymaking tools, are well-chosen. “If we focus on those five items, then we can get somewhere,” said Tomasz Snażyk, chief executive of Startup Poland.

Devil in the detail

But there is also a common criticism of a lack of detail. “The agenda itself says that there will be more documents and programmes to come, but I hope there will also be more vision and more key performance indicators that we, as entrepreneurs and representatives of the ecosystem, can work with,” Snażyk said. Talent is one area of concern. “The talent chapter is the shortest of all, yet talent is the most important thing. That part of the agenda needs to be built upon.” He would also have liked to see explicit plans for bringing Ukraine into the European innovation ecosystem.

For Tumėnas, the most significant gap is around universities and curiosity-driven fundamental research. “Fundamental research, which is critical for innovation in Europe, especially if we are talking about breakthrough innovations, is missing from the communication, as is the full role of universities. They are not just producers of talent and skilled workers, but also players in the innovation ecosystem.”

Others see a lack of attention to the translation of research to innovation. “Many actions target the research, development and testing phase, regulatory sandboxes, Innospace, testing and experimentation facilities, etc,, thereby preserving the EU situation that an excellent research phase is followed by a less successful utilisation phase,” said Dániel Magyar, director of the Eötvös Loránd University Innovation Center in Budapest. “In addition to the funding actions, support measures for market introduction would be needed, such as technology transfer support, the necessary skills development, etc, which would already support direct market introduction on a large scale, not only for the start-up sector, but also for the SME sector.”

For Egita Aizsilniece-Ibema, head of the Latvian Office for Innovation and Technology in Brussels, there is a gap when it comes to finance. “Europe, and Latvia for that matter, are great at producing innovative technologies in laboratories, but risk capital is needed to test it and get it to the market. The Commission knows the challenge of the Baltic countries being small markets for deep tech investors, but I am not sure that the Innovation Agenda addresses this matter,” she said. “We want to ensure that deep-tech start-ups, collaborating with the European Universities, remain and grow in our region. For that to happen, we should provide public risk funding or encourage and assist private risk funding to be active in the Baltic countries.”

Of the detail in the agenda, the most commonly criticised is the focus on deep tech. “There is so much more to innovation than deep tech,” said Kubiak. I’m not sure that deep tech is going to be a strength of the widening countries. It’s an area where we have a lot of catching up to do, so it may be difficult to take this up. [Inclusion of] the more human and social side of innovation would also be very welcome.”

Such a narrow focus may even prevent the efficient uptake of deep tech innovations. “The key issue of the digital transition and the deep tech line is not only the technology, but also the human resources that can apply it professionally and bring it to the market,” Magyar said. “Thus, for example, the support and development of innovation culture, creative industries and social innovation would be an important element, which could bring the developed deep tech solutions closer to the mass of EU economic actors, thus achieving real innovation progress.”

Deeds not words

All agree that how the Innovation Agenda is implemented will the key to its success. “I have really high hopes, but we need to see how the words are translated into actions, and also how these two worlds connect, the EU level and implementing everything on the ground,” Kubiak said. That also represents a challenge for central and eastern European countries and regions. “We are conscious that there is a lot of work to do on our side, to support our innovation ecosystem. All the levels have to meet up if this is going to be a success, and we hope that this will happen,” said Kubiak.

A common concern, ironically enough, is that people who are new to getting involved in EU programmes are not aware of the extent innovation divide, and that not all ecosystems are starting from the same place. “The widening countries are underperforming and have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to research and innovation,” Kubiak said. “Sometimes we are dealing with new partners, for example in Horizon Europe, where we have people who are getting involved for the first time. They have to start small, before they can get involved in bigger projects, and then coordinate projects. We have to remember that for some things that are state-of-the-art in western European countries, we are not ready to reach this level straightaway.” That means it is important to have initiatives that are specifically designed to help with catch-up

As Rus noted, “The third mission of universities, to commercialise knowledge and technologies, is an important element of the ecosystem, and it is a normal thing in Eindhoven or Lund, but it is still completely strange in Slovenia.

As things stand, no mechanisms or processes are in place. “It is only now that we are discussing with the government how to overcome this gap,” Rus said. “Being able to show that this is a high priority for the EU will help in that argument, but so would more support for commercialisation through Horizon Europe. “In some countries, where this commercialisation culture is present, they don’t miss it, but when these mechanisms are missing, we can’t compete.”

Even where there are mechanisms to support commercialisation, countries at which are at a disadvantage may effectively be excluded. Aizsilniece-Ibema points out that there are already limitations on how much use Latvia can get out of the EU schemes intended to support innovation, such as the European Innovation Council (EIC) Transition, which helps mature a novel technology and develop a business case to bring it to market.

The only way to access this funding is to have previously participated in EIC Pathfinder projects, including projects funded under EIC Pathfinder pilot, Horizon 2020 Future and Emerging Technologies (FET-Open, FET-Proactive, and FET Flagships calls, including ERANET calls under the FET work programme, and European Research Council proof of concept projects. Of this list, Latvia can only claim six FET projects.

“This means that SMEs and other organisations that have already produced some results, but are still too premature for the EIC Accelerator are excluded from the EIC just because of the submission restrictions,” she said. “The gap between technology readiness level 3/4 and TRL 5/6 is a vital area where Latvian SMEs need support in order to facilitate the path to the European market and raise widening countries success rate. And this is also the case for many widening countries.”

Innovation silos

Another concern is that implementation might reinforce rather than narrow the innovation gap, if it is not done in the right way. “My worry is that the regional innovation valleys shouldn’t again become some kind of regional silos, which we will have to go back and connect again, again and again,” said Tumėnas. “We need to have a clear understanding of what lies behind these regional innovation valleys. What is written in the agenda is nice, but in practice the situation can be different, and you need to adjust to existing innovation ecosystems in every member state.”

Finally, there is a worry that although the innovation divide features strongly in the agenda, it may slip in the implementation. “Will the programmes finance very innovative projects in less obvious and less centrally-based communities, or will they continue to finance the companies that are growing out of the already established and well-funded communities?” Aizsilniece-Ibema asked. “And, when it comes to very competitive calls, would reduction of the innovation divide in Europe be as important a horizontal priority as involvement of women in innovation?”

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem…

- The European Research Council (ERC) is increasing the budget of its roof of Cocncept grants from €25 million to €30 million in 2023, according to a work programme published this week. These grants go to researchers previously funded by the ERC who want to explore the commercial or social potential of their work, laying the ground for the creation of a start-up. With each grant worth €150,000, the budget will support up to 200 researchers.

- Celus, a Munich-based start-up that uses artificial intelligence to streamline circuit board engineering, raised €25 million in series A funding. Founded in 2018, the company saw a surge in interest thanks to the difficulty in sourcing electronic components during the COVID pandemic, with investors now following suit.

- A public consultation on the compulsory licensing of patents has been launched by the European Commission. In particular, it wants suggestions on how to build a more efficient and coordinated compulsory licensing scheme in the EU. Compulsory licensing is seen as a way of tackling crises, as it can help provide access to key products and technologies where voluntary agreements have failed. “The initiative would not aim to make the use of compulsory licensing more frequent, but to ensure that the system functions more efficiently and that the EU is better equipped to address EU-wide crises,” the Commission says. Submit your views by 29 September 2022.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.