The coronavirus crisis is leading to lower emissions across Europe and around the world. But these reductions are temporary - and, despite a postponement of the global climate summit, experts say now is not the time to put green energy research and climate policy on lockdown

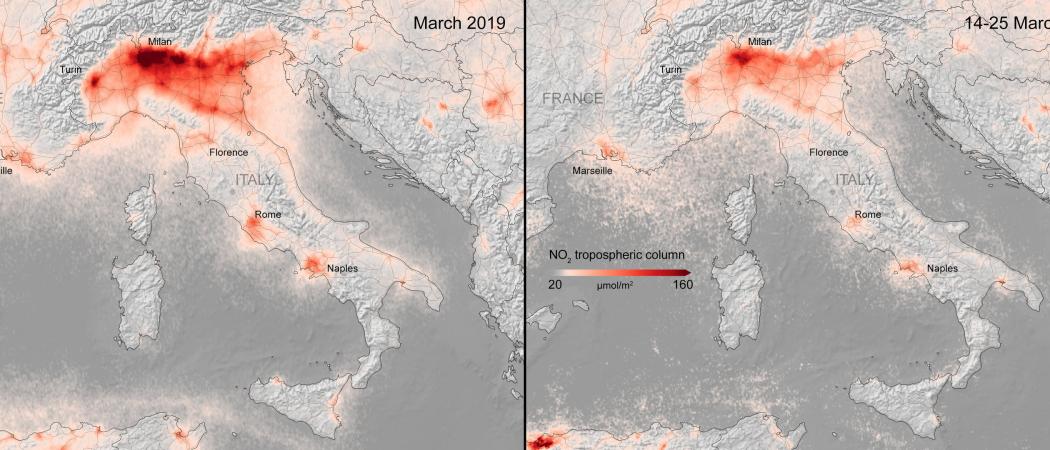

Average nitrogen dioxide concentrations dropped after the Italian government placed the country under lockdown. Image: European Space Agency

After Europe ground to a coronavirus-enforced halt, images captured by one of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Copernicus satellites showed huge reductions in nitrogen dioxide concentrations over Paris, Madrid and Rome from 14 – 25 March, compared to the same week in 2019.

The same is true for China, where the Copernicus satellite recorded a dramatic fall in NO2 released by power stations, factories and vehicles in all major Chinese cities between late January and February. ESA also observed a decrease of around 20 – 30 per cent in fine particulate matter, one of the most important air pollutants, in February 2020 compared to the previous three years.

However, these clear skies are deceptive, climate scientists and policy experts warn.

“We need to make a clear distinction between air quality and climate change,” said Wim Thiery, climate scientist at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. “When we talk about air quality, yes, less traffic, fewer planes and factory shutdowns mean less NO2 and other pollutants over cities. But for the climate it’s much more complex.”

The worry is that although reduced air pollution may bring health gains in the short term, emissions will rise when the crisis ends, and in the meantime climate policy will be sidelined as governments focus first on slowing the spread of the virus, and then on jump-starting stalled economies.

That fear proved fully justified on 1 April, when the British government announced that the COVID-19 crisis is forcing it to postpone the planned COP26 global climate summit, due to take place in Glasgow in November, to an as-yet undetermined date next year. The announcement was accompanied by a warning from Patricia Espinosa, the United Nations’ executive secretary for climate change: “COVID-19 is the most urgent threat facing humanity today, but we cannot forget that climate change is the biggest threat facing humanity over the long term.”

“We might lose half a year to a year in climate negotiations. Finances that have been earmarked for climate will go to other activities,” said Christian Egenhofer, senior research fellow at the Energy, Resources and Climate Change Unit at the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels. “For the next two years all politicians will be focused on re-launching the economy,” he said.

The economic recession, widely believed to be on the cards, is not good news for the climate either.

“Strong economies are better able to cope with change,” said Thiery. “We also have a higher chance of success in reaching climate neutrality if we have strong international collaboration, which may be jeopardised by the coronavirus.”

Hendrik Wouters, climate scientist at the Flemish Institute of Technological Research agrees. “An economic crisis would mean we could not afford an energy transition,” he said. “If the crisis lasts for too long, this would also have an impact on sustainable development. This three-month decrease in emissions will not have a great benefit in the long term.”

There is also the risk there will be an over-compensation of economic activity when the crisis lifts and normal life resumes.

In terms of policymaking, 2020 was primed to be crucial for climate negotiations. Countries are supposed to submit their 2050 plans to the UN, stating what they plan to do to align with the Paris Agreement in both the short- and long-term. But the coronavirus crisis is already delaying several crucial deadlines that should be met before the now-postponed UN climate change conference.

Meanwhile in the EU, rumours have been circling that the European Green Deal may take a back seat for a while as member states pour funds into relaunching their economies.

“At this stage, while the duration of this pandemic is difficult to predict, so are the virus’ effects on climate policies, and respectively the timely delivery of the European Green Deal roadmap for 2020-2021,” said Ilias Grampas, EU Affairs Manager at the European Bureau for Conservation and Development, which manages the Secretariat of the European Parliament Intergroup on Climate Change, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development.

For Grampas, the key factors that will influence climate policy-making in the near future will include how long the pandemic lasts, whether member states adjust their budget allocations, if political leaders choose to support green investments, and whether financial incentives to re-energise EU economies incorporate sustainable growth principles.

Boosting economic growth after the coronavirus lockdown doesn’t mean green objectives must be sidelined, according to Egenhofer. New ways of producing and storing renewable energy, hydrogen fuel and other green technologies might prove more attractive to private investors and governments than traditional industries like coal mines, while the coronavirus shutdown could signal a natural swerve in the direction of cleantech and renewables.

But as prices for oil continue to plummet – partly a result of the ongoing price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, but also due to COVID-19 – renewable alternatives like solar power and wind energy become less competitive, and less interesting to investors.

On an individual level however, the coronavirus lockdown could inspire climate-friendly actions, according to Wouter. “This could be an opportunity to see how we can re-organise our activities to benefit the climate. Home office and teleworking, for example. There are a lot of conferences held every year leading to air traffic and emissions. We can use existing technology to replace these and combat climate change,” he said.

Those campaigning for strong climate policies could also learn from the cooperation seen between experts, politicians and the public in the coronavirus crisis.

“It's remarkable that you see this union being formed between scientists, policymakers and the public. People are asking for strong policies and, based on scientific evidence, policymakers are taking action,' said Thiery.

This article was updated 2 April to reflect news of the COP26 postponement.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.