Armed with bear spray, microbiologist Naowarat ‘Ann’ Cheeptham is searching for hardy, less-studied bacteria that could play a role in stemming the antimicrobial resistance crisis

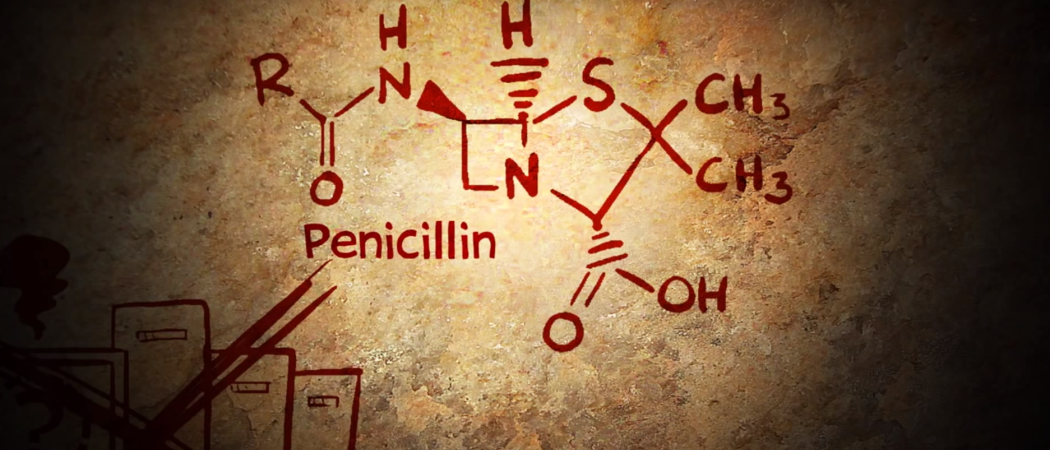

A screen grab from a video by Piled Higher and Deeper (PHD Comics) on Cheeptham's research.

As resistance to existing antibiotics reaches crisis levels, the search for potential natural sources of new drugs is taking one researcher on a mission into slimy underground caves - and into the path of black bears.

“You want to work with [me], you have to prepare to be bear bait,” Naowarat ‘Ann’ Cheeptham, a microbiologist at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia, told the Wired Health 2019 conference in London this week.

Cheeptham is leading a team that forages in hard-to-reach subterranean nooks for rare and unusual microorganisms that can be put into service as the basis of new antibiotics.

“We have no idea how many species are out there. Of all microbial life on earth, we have only studied one per cent or less than one per cent,” Cheeptham said. “My research goes via one cave at a time – it’s a small piece in this whole puzzle to fight AMR.”

‘Perfect storm’

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that there are too few new antibiotics under development to counter the growing risk of untreatable infections.

Most of the new drugs currently in the clinical pipeline are modifications of existing classes of antibiotics and are only short-term solutions. There are very few potential treatments for those antibiotic resistant infections identified by WHO as posing the greatest threat to health, including drug resistant tuberculosis which kills around 250,000 people each year.

Striking gold in the caves is not guaranteed.

Cheeptham’s team has screened more than 2,000 bacteria, and is now zeroing in on two promising microbial strains.

Even two new antibiotics could be a valuable aid in the current crisis. The most recent figures for the EU say there are 25,000 deaths a year from drug resistant infections that previously were treatable.

The journey of antibiotic development is far from easy, however and there has not been a new class of antibiotic since the 1980s.

Antibiotics are not very profitable for pharmaceutical companies; indeed only three are actively involved in the field. “It could take ten to 25 years to get one antibiotic on the shelf,” Cheeptham says, and upwards of $1 billion investment.

There is now serious thought in several countries into new ways to incentivise and reward pharma innovation. One proposal is that companies that develop new antibiotics should receive market entry awards of $1 billion, so they recoup the cost of R&D as soon as a drug is launched.

Cheeptham says her work is propelled by fear of the potentially “dire impacts of a perfect micro-organism storm.” Bacteria evolving resistance to antibiotics are “traveling further than ever before, carrying no passports. Some of them will cause mayhem,” she said.

Bear encounter

The field trips to search for natural sources of new antibiotics can be dangerous work. On a recent visit with colleagues to Canada's Iron Curtain Cave – so called because of its iron deposits – Cheeptham came face to face with a black bear.

“Going into the cave, we tried to make noise, be chatty, because we read that it would keep the bears away,” she said.

But after a tiring day of exploration, her team forget this instruction.

“Coming out, we were so tired; we hiked back in silence,” she said, until coming across a mother bear with her two cubs. “It stopped me dead in my tracks. I was so scared even though I pretended not to be scared. I thought about throwing my samples away and running. When you see a bear, you’re supposed to walk back slowly and lower your body down, so you don’t show any threat.”

She readied her bottle of bear repellent. Unlike hair spray, she explained, you only get one shot. “I ended up spraying out without checking the wind direction. We were coughing like mad; the mother bear was looking on. Luckily, they eventually walked away.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.