Scientific facilities across Europe now have a patchwork of ties with Russia, ranging from business as usual to full expulsion

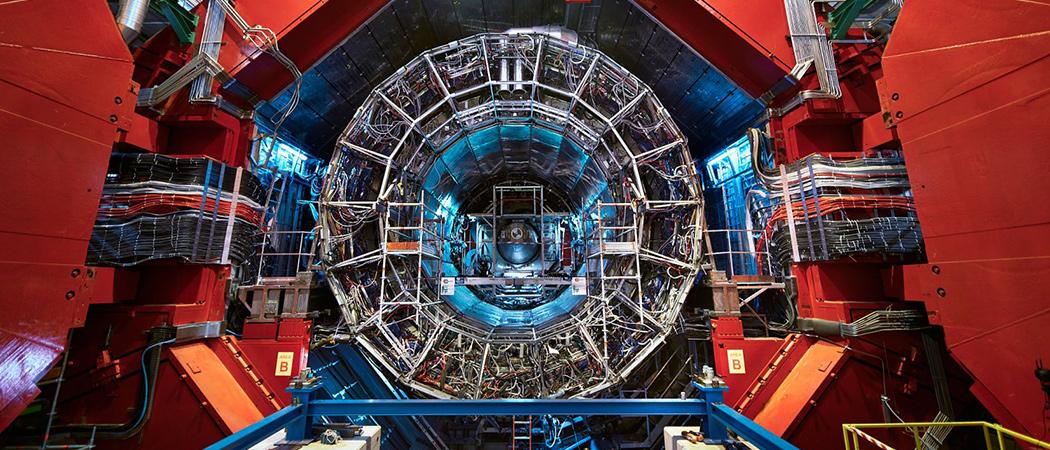

Photo: @CERNpress / twitter

The European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) has said it will cut its ties with Russia when its agreement with the country expires at the end of 2024.

The particle physics lab had already suspended Russia’s observer status and the exchange of funds, materials and personnel with the country in March.

At a CERN council meeting last week, its 23 member states affirmed that the “aggression of one country by another runs against the values for which the organisation stands”.

Russia and CERN signed a cooperation agreement in 2019, but this will not be renewed when it runs out, the council agreed.

However, CERN did leave the door open for a change in policy. “The situation will continue to be monitored carefully and the council stands ready to take any further decision in the light of developments of the situation in Ukraine,” it said.

The lab in Geneva is one of several European research infrastructures that have had to grapple with how to respond to the invasion of Ukraine. Some have cut ties in practice while figuring out whether to eject Russia formally, while others have continued cooperation as it was pre-war.

ITER, the decades-long effort to build a fusion power plant prototype in the south of France, for example, has not made any changes to Russian participation as a result of the invasion.

Its council met last week, but the Ukraine situation was not discussed, a spokesman confirmed. “There is no change to Russia’s involvement in the ITER project,” he said.

The project is more international than CERN, and has Russia, the US, India, China, South Korea and Japan as full members, as well as European nations. There is no provision in its founding agreement for removing a member.

In addition to being a founder member, Russia is an active contributor to the construction of ITER. For example, it is a major supplier of the niobium-tin superconducting material for ITER’s magnets and is manufacturing crucial components including gyrotrons, the energy-generating devices in the electron cyclotron resonance heating system. Russia will supply eight of these devices in total, one third of the total installed capacity on the ITER machine.

Russia also has constructed and tested a full scale prototype of the ‘director dome’ the component at the base of the plasma chamber that extracts heat and ash produced by the fusion reactor. This was delivered from Russia to ITER in December 2021.

There has also long been an explicit carve-out for ITER in EU sanctions against Russia that pre-date the Ukraine invasion.

Frozen out

Meanwhile in Germany, the European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Facility (XFEL) also still has Russia as a member, but discussions about Russia’s status are thought to be ongoing.

“No decisions have been taken yet,” said a spokesman. However, in practice, relations with Russia have been on ice since March, with existing collaborations frozen and new ones prohibited.

Russia also continues to be a member of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, contributing 6% of its budget. But like XFEL, in practice collaboration is on hold. Since March, new and existing collaborations have been suspended with Russia.

Earlier this month, members of the Arctic Council excluding Russia – made up of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the US - said they would implement a “limited resumption” of the body’s work, but only in projects that do not involve Russia.

The suspension of the council’s work was one of the early scientific casualties of the war, threatening projects exploring the impact of climate change.

A spokeswoman for the Swedish government said that there are more than 120 projects approved by the council, although it was still too early to say exactly which ones would now be able to resume.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.