As demand for science and engineering professionals continues to grow, the EU sees a window of opportunity to attract talent from the US

Photo credits: Jeswin Thomas / Unsplash

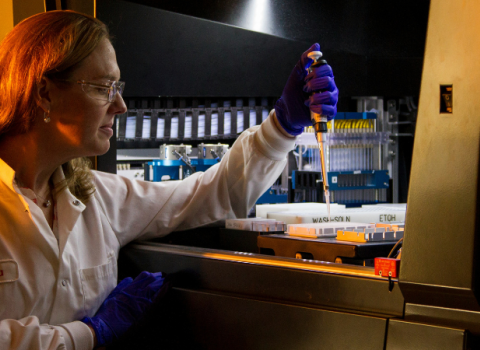

The EU is looking to train more professionals in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines to spur new technologies and drive economic growth, but some of the deficit in advanced skills would have to come from abroad, experts say.

The European Commission says the EU needs an additional two million professionals in science and engineering. Its new STEM Education Strategic Plan could help plug that gap by encouraging member states to anchor STEM disciplines in national education policy, increase the number of STEM students, and also attract research talent from abroad.

Robert-Jan Smits, outgoing president of the executive board at the Technical University of Eindhoven (TU/e) is happy to hear that the Commission is finally acting on this issue. The STEM skills gap hinders innovation in Europe, he told Science|Business, and universities like the TU/e are doing their best to train new STEM students, but it’s very difficult to keep up with the demand. “Even if we would double the numbers of our graduates, it would still not be enough,” he said.

This has been a problem for many years, he went on. By 2030 the industry in the Eindhoven region alone would need an additional 10,000 university engineers, a demand that is unlikely to be met. The danger, according to Smits, is that the semiconductor industry in the region will not be able to grow fast enough.

By 2030, the Commission wants member states to have at least 45% of students in secondary schools enrolled in STEM fields. In universities, that figure should be at least 32%.

Roxana Mînzatu, the commissioner responsible for social rights and skills, says EU-wide demand for additional workers in science and engineering professions is only set to intensify in the next decades. “There is a demographic reality that tells us that we are losing active labour force due to aging, and industries need much more capacity,” she said.

For this reason, it should also be a priority to draw in more international talent. The Commission’s plan includes three new pilot programmes aimed at luring young researchers and professionals to Europe. One of the pilots will allocate funds through Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions to attract PhDs and postdocs in Europe, while a new visa strategy would help attract more researchers and other STEM professionals.

Ivana Didak, head of higher education policy at The Guild of European Research-Intensive Universities says the pilot programmes have the potential to attract STEM talent to Europe. However, she warns that the EU should continue to support both inward and outward mobility of researchers.

But, as the new Trump administration is wreaking havoc in science and technology, the EU could swoop in and attract talent from across the Atlantic. Smits says the EU has historically lost researchers to the US and now has an opportunity to reverse the trend. “You have to go for it, as just for demographic reasons we can’t get enough engineers, so we need to shop somewhere else.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.