European Space Agency director Johann-Dietrich Wörner talks to Science|Business about returning to the moon, and growing competition in a new spaceflight era

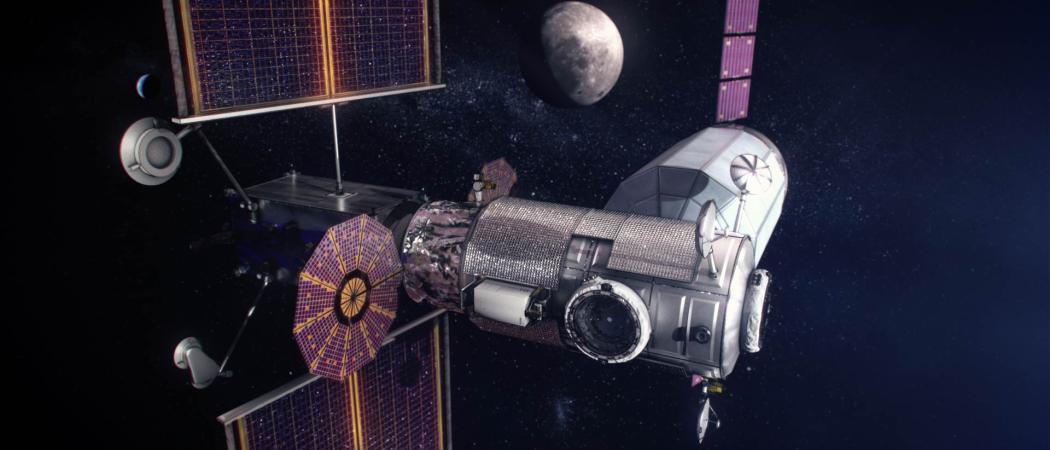

Concept art of the Lunar Gateway space station as it is intended to appear in 2024. Photo: NASA.

Europe is building a “bus stop in space” to give astronauts a pit stop during their history-making return to the moon for the first time in almost 50 years, says the head of the European Space Agency (ESA).

The Lunar Gateway, a space station to be placed in orbit around the moon by NASA and ESA in the 2020s, will provide a staging post for astronauts going to the Earth’s celestial companion, and eventually Mars, says director-general Johann-Dietrich Wörner.

“It’s very important to see manned flights back to the moon,” Wörner told Science|Business. It is 48 years since American astronauts walked on the moon; no Europeans have been on its surface.

The station will serve as a half-way house between the Earth and the moon, Wörner said, acting as a place of shelter and a launch pad for missions further out into the solar system.

Enthusiasm for lunar exploration had been waning over the decades, but has been boosted again in recent years by cheaper technology and the increasing involvement of private companies such as SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic.

“After [the] Apollo [17 moon landing], everyone decided the next big thing was to go to Mars. But it takes two years to go there and back, with all the risks of radiation to astronauts’ health. We’ll do manned trips to Mars, but not very soon,” Wörner said.

“Some people said the moon was just a dead rock, why go back? But it’s fascinating, it can tell us about the history of the earth,” he said.

ESA is working with the Americans, and Canadian and Japanese space agencies, on a further mission to mine the moon’s reserves of water ice – a potentially invaluable drinking source for future astronauts. Oxygen removed from the water could also provide the basis for breathable air, or for rocket propellant.

If this scientific mission is a success, it could be the first step towards a sustainable human presence in space.

“So the moon is something of utmost importance,” Wörner said. “There is also the geopolitical aspect. An international moon village should be something we build together with other countries.”

The village, a proposed successor of the International Space Station, could be made by robots and 3D printers sometime around 2050, Wörner added.

The lunar mission is one of a diverse set of projects the Paris-based agency will be involved in over the next five years. The agency is also searching for a replacement for Wörner, whose mandate ends mid-2021.

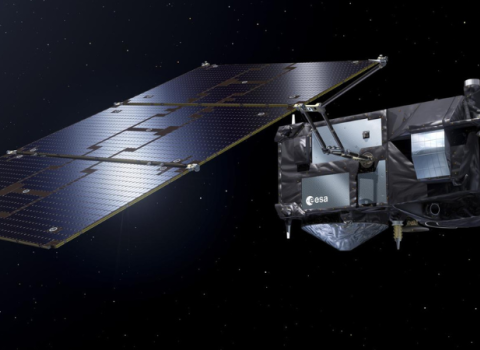

US and European space agencies have recently began an effort to bring samples of Mars rock and soil back to Earth. Later this year, ESA will launch another earth-observation satellite to join the Sentinel fleet.

Wörner also promises a plan to tackle space debris. The threat from thousands of dead satellites that continue to circle the planet is an issue of growing concern for the agency.

With the number of space-faring nations rising to 70, following the United Arab Emirates’ historic recent Mars probe launch, off planet clutter is growing. Of the 114 satellite launches in 2018, only eight were European, compared to 39 Chinese, 34 US, and 20 Russian.

Founded by 22 European countries, ESA last year received an unexpectedly high budget of €14.5 billion for five years. At €200,000 more than the requested €14.3 billion, it was the agency’s biggest budget increase in 25 years.

Germany is the biggest financial backer of the agency, committing almost 23 per cent of the total budget, followed by France on 18.5 per cent, Italy 15.9 per cent and the UK 11.5 per cent. In 2019, the ESA had a total budget of €5.72 billion, about a third of its US counterpart NASA's budget.

New spaceflight era

The US ignited a new spaceflight era in May, when billionaire Elon Musk’s SpaceX became the first private company to launch astronauts to orbit. Millions around the world watched the launch online and on television.

“Musk is a visionary. He’s doing a great job for space. He’s helping to shift the paradigm,” Wörner said.

Europe “cannot and should not copy what he has done,” the German added. But Wörner said it had inspired everyone involved in space to go further. “Space is cooperation and competition. Nobody would run 100 metres in less than 20 seconds if there wasn’t a competitor,” he said.

ESA’s lunar plan follows China’s ground-breaking landing on the far side of the moon last year.

Planned Chinese and US manned missions to the moon, and eventually Mars, help stir memories of the Cold War space rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union.

“China-US is a political situation that’s not so nice right now,” said Wörner, on the increasingly tense political relationship.

“But in space, we’re above the earthly crises. There might be some issues, but we can always find ways to work better together. We are going to be working together with China, though maybe not as intensively as [we do] with the US,” Wörner said.

The director says he would drop everything “in a second” for a chance to go up to space. “I would do it today. I would immediately cancel all my Zoom appointments,” Wörner said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.