Eurospace annual report shows recent growth in the space sector is entirely driven by SpaceX and Chinese programmes

Starlink Mission. Photo credits: Official SpaceX Photos / Flickr

The European space industry is lagging behind due to a drop in commercial demand and a lack of military spending, according to the latest annual report from industry association Eurospace.

The sector has also been hit by technical problems, most notably the four-year delay in launching the Ariane 6 rocket. It finally lifted-off on 9 July, restoring Europe’s sovereign access to space.

That may boost the industry’s prospects. But, said Olivier Lemaitre, secretary general of Eurospace, “We should not bury our heads in the sand. The economic situation in the sector unfortunately has deteriorated significantly.”

This deterioration has happened at a time when the commercial space sector is booming. The total mass deployed to space, one measure of activity, has grown significantly since 2019.

However, 95% of the growth in commercial space programmes is due to the launch of the Starlink satellite constellation, owned by Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

However, noted Pierre Lionnet, research director at Eurospace, SpaceX builds all its own satellites. “In terms of business opportunities for building satellites, the demand [from] Starlink doesn’t exist.”

Starlink apart, commercial constellations deploy smaller satellites that generate less revenue for companies than government-funded space programmes.

Meanwhile, demand for satellites in geostationary orbit, which used to be the largest segment of the commercial market, is decreasing as TV broadcasters are squeezed by streaming services.

Eurospace surveyed space companies operating in Europe and found that, while revenues from publicly funded European programmes are increasing, commercial sales and exports have been falling since their peak in 2017.

“We need to find some solutions to compensate that loss, because we do not expect this commercial market to grow significantly in the coming years,” said Lionnet.

Public sector demand

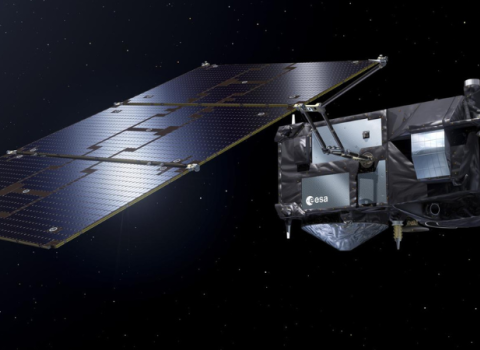

Publicly funded bodies, including the European Space Agency (ESA), national space agencies, the European Commission and Eumetsat, the intergovernmental satellite agency that monitors weather, climate and the environment, now represent 70% of the market for European space companies.

ESA is the primary customer, contributing €3.7 billion in annual revenues, including programmes delegated to ESA by the Commission or Eumetsat.

Eurospace points out overall revenues would be higher were it not for technical and administrative delays, including to Ariane 6.

However, public spending in Europe is still far behind other space powers. NASA invests approximately three times more than ESA, and publicly funded launch demand remains relatively low in Europe.

Following an EU Council meeting in May, ministers called for more public and private investment in space. Timo Pesonen, director general for defence industry and space at the European Commission, said there needs to be a “much bigger” space programme in the EU’s next long-term budget from 2028.

Military spending

The discrepancy is in large part explained by Europe’s modest investment in military space activities compared to other space powers. The mass deployed to space on behalf of European government programmes in the last decade, excluding human spaceflight, represented on average 12% of civil programmes, but just 2% of military programmes.

“Strategic considerations have not been a major driver of space systems development in the early years of European space programmes, and today European space military programmes are still organised at national level rather than at European level,” the report says.

Apart from human spaceflight, military programmes represent the main opportunity for business growth. “They go after the most advanced technology, and there are a lot of requirements that are not there for civil programmes,” said Lionnet.

In terms of public funding, Chinese space programmes represent 99% of the growth in space activity in the past five years, according to the Eurospace report. This is driven by a growing investment in military programmes, a recent commitment to human spaceflight and investment in the Tiangong space station.

The European market meanwhile is held back by the lack of a human spaceflight programme. While US, Russia, China and soon India are all capable of launching astronauts into space, Europe is not.

ESA chiefs want to change that. The agency recently announced Germany’s Exploration Company and Italy-based Thales Alenia Space as the winners of a competition to develop a vehicle to deliver cargo to and from low Earth orbit. One of the specifications is that the vehicle must have the potential to transport crew in the future without major modifications.

The competition is part of a wider shake-up of ESA procurement policy designed to stimulate competition. The real test comes in 2025, when ESA member states have to agree on the agency’s next three-year budget.

The full Eurospace report is available to companies participating in the survey and selected European institutions, but the main figures are here.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.