With the Ariane 6 rocket four years late and Russia’s Soyuz off-limits, Europe has no guaranteed access to space. Competition commissioner Thierry Breton pledges to change that in the next EU space programme

European commissioner for the internal market, Thierry Breton, speaking at the European Space Conference in Brussels. Photo: European Space Conference

Europe is facing an “unprecedented crisis” having lost its independent access to space, commissioner for the internal market Thierry Breton said, as he called on the EU to take a greater role in protecting the continent’s interests.

“It is time for a paradigm shift, so that we define and think European launcher policy within an EU framework,” Breton told the 16th annual European Space Conference in Brussels on Tuesday.

In the next EU space programme, due to begin in 2028, the Commission wants to include “a fully-fledged access-to-space component,” he said. This will cover industrial policy, “from R&D, to deployment and readiness, including security and defence dimensions.”

Europe does not currently have sovereign access to space, due to delays to the Ariane 6 and Vega-C rockets, and loss of access to Russia’s Soyuz rockets following the invasion of Ukraine.

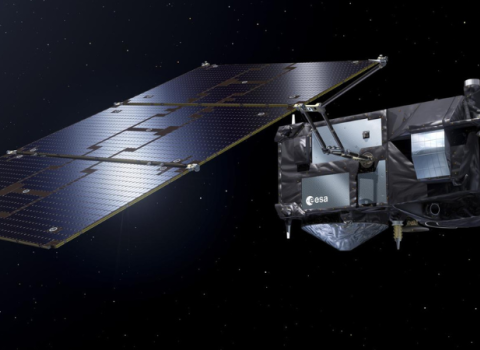

In the meantime, the EU was forced to turn to US company SpaceX to maintain its space programme, including the launch of two Galileo navigation satellites in April, and two more in July.

At the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Space Summit last November, member states agreed to launch two competitions for private companies, to develop a launcher, and a vehicle to transport cargo to the International Space Station and back to earth by 2028.

This is “a good first step”, Breton said, but he added, “We need to go further, and join forces to radically change our European approach.”

The European Commission is ready to lead those efforts, by aggregating European demand for launch services, from the EU, ESA, and member states, including defence ministries, “with a clear European preference”.

The Commission is working with member states on this, and Breton hopes the initiative will be in place before the EU’s next long-term budget cycle starts in 2028.

Flight ticket

The EU has taken steps to promote competition in the space sector. On Tuesday, together with ESA, it announced the first five companies selected for the flight ticket initiative, which aims to stimulate new European launch systems. These companies will be awarded a frame contract and will be able to compete for orders for EU and ESA launch service needs.

Breton said 2024 will be critical in shaping European space policy, with the Commission due to present proposals for an EU space law in the coming weeks to create a “true EU single market for space.”

Currently, the legal framework differs from country to country. This “prevents us from acting as a bloc with the necessary size to matter,” Breton said.

The EU space law will set out common rules on safety, resilience and sustainability. It will aim to reduce collisions and damage caused by space debris, protect space assets against threats such as cyberattacks, and ensure space activities are sustainable. It is hoped these rules will come to set the standard at a global level.

Europe is too reliant on third countries, and needs to develop new capacities to monitor its space infrastructure, detect potential threats, and react to them in time, Breton said.

Breton also wants to “fully unlock the potential of EU space programmes for defence”, while increasing synergies with innovation projects under the European Defence Fund to develop new services.

“Recognising space as an element of our collective security was taboo a few years ago,” he said. The war in Ukraine has since shown the importance of satellite constellations for military operations, for example.

Thomas Dermine, the minister in charge of science policy for Belgium, which recently assumed the rotating presidency of the EU Council, urged member states to pool defence resources to fund ESA’s space activities, echoing comments made by ESA chief Josef Aschbacher last week.

“We believe the only way, if we want to significantly increase the resources ESA has for its own policies, is to use security and defence financial means,” Dermine said. “If you look at how the Indians, or the Chinese, or the Americans are funding their space programmes, they do it mostly for security and defence reasons.”

Belgium uses military funding to fund ESA on dual-use technologies, and he wants other member states to follow suit, as space becomes increasingly critical for security.

The possibility of a second Donald Trump presidency should be a “wakeup call”, reminding Europe that it needs to develop its own capabilities and cannot take American support for granted, Dermine said.

Companies meanwhile say the vast disparities between the US and European space budgets raise questions over the sustainability of European industry, even as many new startups emerge on the scene.

“Low institutional demand, coupled with low profitability exacerbated by inflation, is putting pressure on space actors and especially on the supply chain,” said Jean-Marc Nasr, head of space systems at Airbus Defence and Space and president of trade association ASD-Eurospace.

“The global profitability of the space sector in Europe is at unprecedented lows,” he said, calling for Europe, customers and the industry to better share the risks and rewards of innovation.

ESA has acknowledged change is needed. After the launcher and cargo return vehicle challenges, “adapting procurement rules will be the next big step we must take,” Aschbacher said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.