The European Commission is planning a decade-long €1 billion megaproject to promote and incubate a range of quantum technologies and translate its investment in basic research through to breakthroughs in computing, sensing, communication, measuring and simulation.

Over the past 20 years the EU has invested €500 million in this area of physics. As a result, Europe has supremacy in basic quantum research, said Anton Zeilinger, a quantum physicist at the University of Vienna, “But the danger is we’ll see again what we’ve seen many times before – that the [commercial] benefits are reaped elsewhere by others.”

One single fact underlines this: Europe leads in quantum science publications, but is patenting less than the US, Japan, China and South Korea.

The pressure is on, agrees Tommaso Calarco, head of the Integrated Quantum Science and Technology centre at the Universities of Ulm and Stuttgart. “Europe is not going to lose the lead in quantum next year, but we will in next five years without a flagship,” he said.

Calarco is co-author of the ‘Quantum Manifesto’, published in March, which is the impetus behind the initiative. The manifesto has been signed by more than 3,000 people.

Alongside the research programme, other ways of advancing quantum technology are being explored in Brussels, including the formation of a dedicated ‘quantum innovation fund’.

€1 billion is the least the EU should be putting up to fend off competition in the field from the US and China, Zeilinger said. He is also critical of the small amount of cash offered up by EU governments, saying, “With the exception of the UK, no European country is investing enough in the field.”

Zeilinger became impatient at the lack of European funding and is now working with the Chinese Academy of Sciences on a project that aims to put a quantum satellite in space. The satellite would form the basis of a communications system which is theoretically "unhackable" and might allow data to be transferred at the speed of light.

“The European Space Agency is slow at making decisions so we accepted China’s offer,” Zeilinger said.

Distant dreams

In terms of the exploitation of possible industrial applications, “You could argue that the US is ahead of Europe,” said Peter Bentley, author and computer scientist at University College London. “In areas such as fundamental science and simulation, you could argue that Europe is ahead,” he said.

While many labs across Europe are exploring quantum theory, the experimental work is happening almost exclusively in western European countries, said Calarco.

The British government is investing €270 million over five years for four quantum technology hubs. In Germany, the government has made research into secure quantum communications a priority, with €9.5 million funding over three years, while the Netherlands is investing €130 million to build a quantum computer.

In theory, quantum computers would be a huge advance on today’s systems. Proponents say they could transform modelling in financial markets, lead to massive improvements in cryptography and revolutionise artificial intelligence.

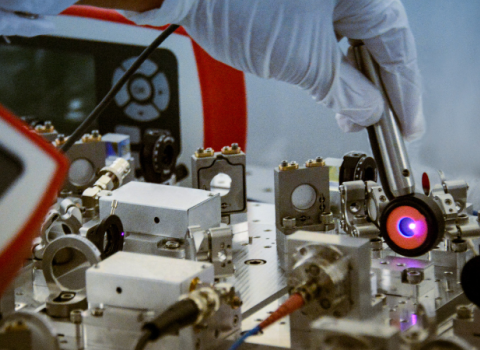

Quantum computers exploit qubits (quantum bits), which can exist in different states simultaneously: at any point in time a qubit can either be a zero, a one, or both. This gives quantum machines a far larger number of possibilities than traditional zero-or-one bit computers, resulting in greater speed and power.

While it is early days for quantum machines, several of the world’s biggest technology companies are investing in the field, with Google, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, Lockheed Martin and IBM each having dedicated quantum computing research groups.

The Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has signed a 15-year partnership with the Chinese Academy of Sciences to open a Shanghai-based quantum computing lab.

Lockheed and Google each own what is promoted as the first and only commercially-available quantum computer, the $10 million D-Wave. The system is manufactured by a Vancouver-based start-up of the same name, which has backing from Amazon founder and chief executive Jeff Bezos.

But many scientists, Calarco included, believe the machine stretches the definition of quantum.

“It is hard to measure the progress of all these efforts,” said Marco Genovese, a quantum physicist at the Italian National Institute of Metrological Research in Turin.

Encouraging Activity

The amounts being invested in quantum computing and other applications of quantum phenomena are lower in Europe than the US. But there is some encouraging activity, according to Richard Murray, Innovate UK’s lead for emerging technologies and industries, which is funding a £150 million UK network of quantum technology hubs based in Birmingham, Glasgow, Oxford and York.

Murray says companies such as MuQuans, E2V and Thales are developing near-term applications in quantum sensing and metrology. However, as yet, breakthroughs in the lab cannot be fully repeated. “There are devices tested right now which can measure gravity ten times more accurately. But any industry applications related to this discovery only show two to three times the improvement,” Murray said.

US computer giants Microsoft and Intel are working with Qutech, an institute in Delft, to build a quantum computer, with the Dutch government chipping in €135 million.

“Microsoft helps with the algorithms and the quantum compilers. Intel provides us with chips and wafers,” said Leo Kouwenhoven, QuTech’s scientific director and professor at TU Delft. However, he believes quantum computing is a decade away from commercial viability.

Learning from mistakes

The new flagship programme is modelled on the Graphene Flagship and Human Brain Project, unveiled with great fanfare in 2013, which are dedicated to developing and implementing graphene-based technology and producing a complete computer model of a brain, respectively.

Both programmes have been criticised, for different reasons. The brain project has been scarred by very public infighting about its scientific objectives, while the graphene project has yet to register a mark on Europe’s industrial landscape.

The Commission deliberately skipped the much-hyped launch of the other flagships, said Calarco. “We want to learn from these experiences and do some things differently. We want a broad, inclusive basis, not something attached to an individual, a university and a country. We don’t want to make big claims either,” he said. “That’s why we’re barely visible in the manifesto – we wanted our names in footnotes, font size 10.”

The Graphene and Human Brain Flagships were selected from six candidates, in open competition. With no formal competition for the latest flagship, some scientists felt isolated from the process. It did not help much that the project’s announcement was folded into a long document published two weeks ago, describing plans to “digitise European industry”.

“I am aware of the objections from some scientists. Some have complained about a lack of competition. I understand. It’s not unexpected that people have reasons to be unhappy,” said Calarco. However, he said, “It is not like someone clicked their fingers and the flagship popped up. Twenty-four funding agencies from 22 countries came together to say we want quantum funded.”

A public consultation on flagship ideas ran until the end of April. Asked whether there was a lack of transparency behind the announcement, Commission spokeswoman Nathalie Vandystadt said, “The initiative does not prevent other flagships [from being] launched.”

Murray said, “There’s a compromise between starting very quickly and setting it up properly and not isolating anybody. He added, “If you look closely at the wording of the Commission press release, it says flagship-scale rather than just flagship. I hope it will be flexible.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.