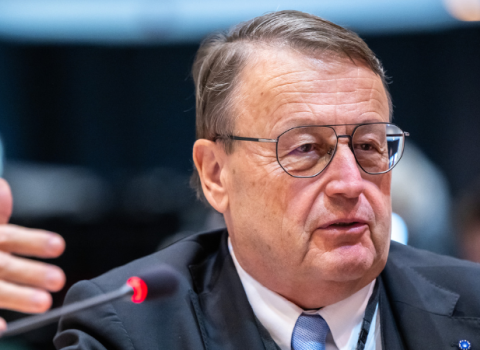

It takes time to nurture revolutionary, disruptive technology, and rather than writing off the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) after the highly critical report from the European Court of Auditors (ECA), the Commission should stand firm, renew its support and be patient, says Richard Templer, professor at Imperial College London and former director of the UK arm of EIT’s Climate-KIC.

Some of the work that the EIT is sponsoring is world-leading and more is sure to come, he said. But from its formation in 2008, the institute has been under political pressure “to demonstrate success tomorrow.” However, breakthroughs take time. “The EIT mandate is to nurture revolutionary, disruptive technology – the kind Europe doesn’t do well anymore,” said Templer. “I think the Commission needs to show patience and guts,” he told Science|Business.

The Commission should say to the EIT, “Have trust in the KICs, give them the space and time to become world-leading and we’ll back you up,” Templer said. “Commissioner Navracsics should be willing to take any brickbats that come EIT’s way.”

European universities and companies are generally good at doing evolutionary, step-by-step innovation and changing this mind-set is not easy. “You can’t expect a sea-change overnight. For example, energy innovation takes 10 to 15 years, minimum,” said Templer said.

He believes part of the problem is that the EIT has undersold its KICs’ achievements. In fact, they have produced some real stand-out successes. For example, within Climate-KIC, KLM airlines flew a plane from Amsterdam Schiphol to JFK airport in the US on biofuel in 2013. “That was pretty exceptional – and it wouldn’t have happened without the stimulus of EIT money,” said Templer.

Templer empathises with the managers of EIT, who have faced criticism from the ECA and from DG Education, which oversees the institute. “I do not envy [EIT director] Martin Kern – he lives between a rock and a hard place. His core dilemma is that innovation requires innovator and investor to act as a team, but the culture of the Commission runs counter to the trust and engagement that is needed.”

The EIT’s mandate requires it to create links between education and industry to bridge the innovation gap. It co-funds five KICs (Knowledge and Innovation Communities) of researchers from academia and industry in the fields climate change, sustainable energy, digital technology, life sciences and raw materials.

Templer claims the Climate-KIC has created a world-leading clean tech acceleration programme. From 2012 – 2015 his UK centre spawned 27 start-ups, which raised $65.5 million of investment over that period, and are on track to raise a total of $120 million within the next two years.

For every euro spent by the EIT, €12 of external, mostly private funds has been pulled in. “These figures are in the Premier League,” Templer said.

Investment raised by UK-based Climate-KIC start-ups

It is dispiriting that the EIT has not used these investment figures as a way of judging the performance of a KIC, said Templer.

“I would claim that the market is the best judge – perhaps the only relevant judge – of whether or not one is doing a good job translating new ideas into products and services, but it is not currently used by EIT.”

Rather, EIT reports simple results, such the number of new companies created. This is clearly less relevant than the investment return, but Templer said, “It is a figure that they find easier to ratify. A KIC’s claim in the success of a start-up may appear nebulous, when I think this kind of is at the very heart of what KICs should be doing.”

Casting doubt on ECA findings

Templer also challenges some of the reported conclusions of the ECA report, for example, the view that because some KIC partners are involved in selecting proposals this risks creating a conflict of interest and generating a lack of trust in the KICs.

A high level of scrutiny means there is no question over fair allocation of funding, Templer claims. “The Climate-KIC always endeavoured to be above board. Proposals for projects would be reviewed externally and ranked, before appearing in the annual business plan submitted to the EIT. Here, EIT would get further external review and EIT staff review before the KIC was interviewed by the EIT governing board for final approval,” he said.

The report also criticised EIT for concentrating its grant awards in a few countries in west Europe. But this is inevitable, says Templer. “I don’t think many post-Soviet countries have the resources and foundations to hit the ground running and drive high innovation performance. Given that this was an essential requirement when bidding to become a KIC the results should not be surprising.”

“The bias has obvious origins,” Templer said, noting that the Climate-KIC included regions of Poland and Hungary from the beginning, in an effort to be inclusive.

In addition, the ECA cast doubt on the ability of the KICs to meet the requirement of becoming financially independent within 15 years. But, said Templer, what is the hurry? “By doing that, you’re basically designing the EIT out of existence.”

The KICs will need continuing support at some level, he believes. “In climate change for example, there is a well-known market failure. This will not disappear tomorrow and there is a demonstrable benefit to the citizen through the use of their taxes to build a low-carbon and resilient economy,” said Templer. “The KICs could and I believe should become long-term strategic partners to the Commission”.

However, Templer endorses one conclusion of the report, which is that the annual cycle of EIT funding is a major handicap for smaller companies. This is absolutely true, he says. “You don’t know if you’re going to get money for projects in the next year, meaning we were unable to guarantee SMEs’ contracts without the support of bigger partners. This needs thinking through.”

There are occasional operational hang-ups getting in the way of further success. “The KICs are doing a good job but are hindered by the way the EIT operates,” said Templer.

For instance, a fair portion of KIC funding goes to auditing, which many partners see as excessive. Templer recalls a four month period where he and several staff were almost fully occupied by four audits, one after the other.

The EIT’s main focus was on demonstrating that financial and administrative processes were perfected rather than work with the Climate-KIC to support its innovation.

“I invited EIT staff to come and spend time in the UK co-location centre to see what it was we were doing – so that they could get a real feel for what the money was being spent on. This never happened and I think the feeling at headquarters was that staff would go native if they went to a KIC; that they would become polluted or biased towards that KIC,” said Templer. “This timidity was a huge disappointment to me. It was clear that the EIT did not see itself as an engaged investor.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.