The country is trying new things and seeking a deeper partnership with Europe to boost its faltering global research profile and keep ahead of Asian rivals

Tokyo bay at night. Photo: Bigstock

Japan is making changes to how it funds and manages research amid growing concern about the country’s sliding status in science.

An increase in spending announced by prime minister Shinzo Abe in late 2019 includes significant funds for young scientific researchers and mission-oriented ‘moonshot’ research projects. The stimulus package is an implicit acknowledgment that the world's third-largest economy needs fresh momentum, and new ways to build science expertise and attract talent.

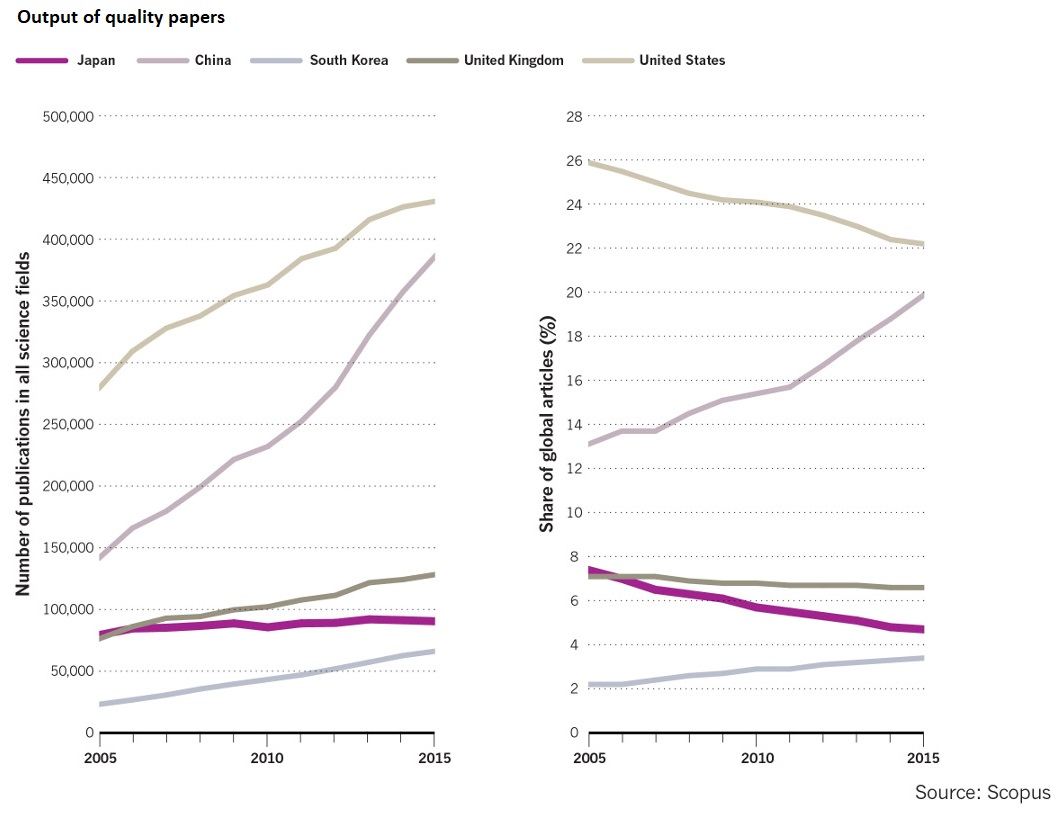

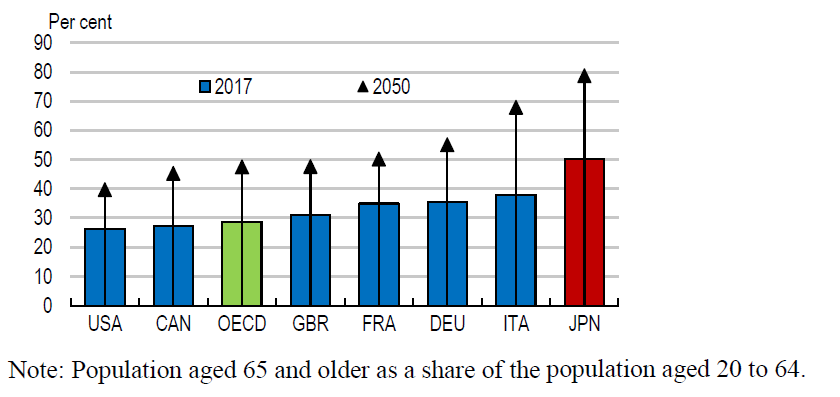

A shrinking and rapidly ageing population, coupled with the biggest debt in the developed world relative to the size of its economy, is seen as a threat to Japan’s status as a leading science nation, with concerns the quality of the country’s research output is stagnating, as that of its neighbours, China and South Korea, is on the rise.

The country’s share of high-quality research papers has dipped, prompting moves to make Japan a top research destination for the world’s scientists.

But for all the challenges it faces, Japan remains one of the most research-intensive countries in the world. According to the Institute for Scientific Information, in 2018 it devoted over 3 per cent of GDP to R&D, higher than the EU average of 2 per cent and the 2.7 per cent invested in the US.

Research strengths include induced pluripotent stem cell technology, robotics, chemicals and computer science.

Regaining strength

A period of stagnant R&D funding has left a mark on universities and research institutions, however. For example Riken, the largest publicly-funded science institution in Japan, has had a 20 per cent budget cut in the last 10 years.

Despite this, Japan has managed to keep its position among the top 10 countries for performing scientific research, and the country’s 2018 science and technology budget delivered 250.4 billion yen (€2.1 billion) in new money – a 7 per cent increase.

Key business strengths in Japan include information technology, sensor devices and supercomputers. Robotics is a booming sector, while artificial intelligence-related patent applications are growing, albeit at a much slower rate than in China and the US. Offshore wind, meanwhile, is an area the government is keen to develop.

In the private sector, large corporations dominate, performing almost 75 per cent of all research. Japan, like Europe, has trouble growing companies, with venture capital and risk-taking in relatively short supply

Since 1995, the government has set out ‘Science and Technology Basic Plans’ covering five-year periods that establish the main research priorities, with a focus on challenges such as the ageing population.

Shooting for the moon

The government is trying to change the way R&D happens in Japan, to make it more goal-oriented, more international, and a bigger draw for talented overseas researchers.

The moonshot R&D programme currently under development, is a five-year plan targeting societal challenges and disruptive innovation.

Around 100 billion yen (€830 million) has been put aside for the moonshots in 2020, as part of a 10 per cent overall increase on Japan’s 2019 research spend. The government wants the moonshots to catalyse a wide range of interactions, between young and old, physicists, chemists, traditional materials scientists and companies. Scientists from around the world are encouraged to submit proposals.

Moonshot ideas include automating all jobs in agriculture by 2040, eliminating all plastic waste from the earth by 2050, devising hibernation technology to mimic the metabolic state of naturally hibernating animals - which during winter sleep are very resistant to serious injury - in humans, and making it possible to “travel” by avatar, making virtual visits to other countries while physically staying at home.

Japan looks to Horizon Europe

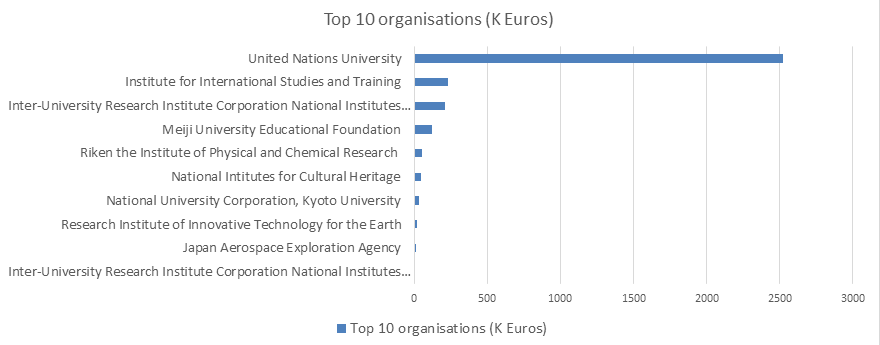

Another element of the strategy to boost Japan’s science position involves strengthening overseas collaboration. In general, Japanese institutions have a limited international presence, but this is gradually changing. For example, Riken opened an office in Brussels in 2018 to expand science collaboration with Europe, by plugging into the policy and funding world around EU R&D programmes.

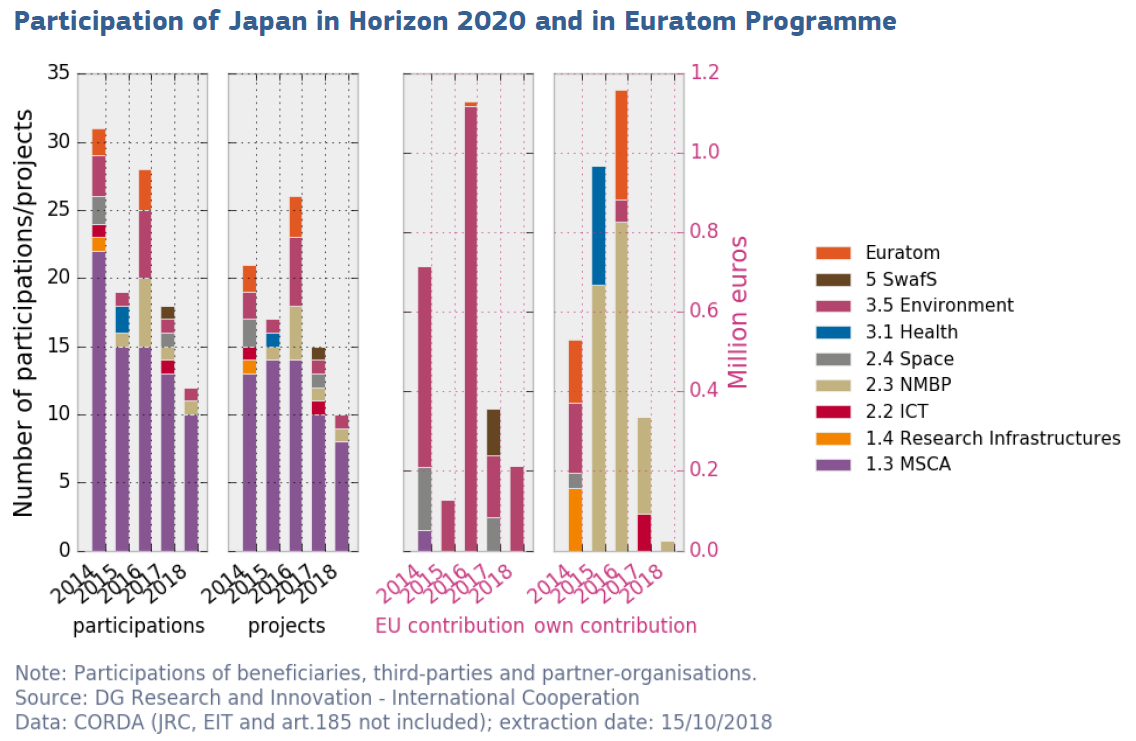

Japan’s government is exploring the option of becoming more deeply involved in the EU’s next €94.1 billion R&D programme, Horizon Europe.

Japan and the EU have various forms of research cooperation under the umbrella of a 2011 Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement. One recent area of increased cooperation is in promoting a human-centric approach to artificial intelligence.

Japan is not automatically eligible for EU funding; however, it can participate in EU-funded projects if it covers its own costs.

In an interview with Science|Business in 2019, Japanese minister for innovation policy Koichi Akaishi said the government might budget about €10 million a year for greater EU scientific cooperation.

However, until the European Commission has finished drafting the next framework programme and set the terms for associate countries, negotiations are at a standstill. Progress in increasing the membership has been stymied by the commission’s unwillingness so far to propose specific terms, for fear that could upset negotiations with the UK on Brexit and over the EU’s 2021 – 2027 budget.

Attracting foreign students

The government is also keen to promote more international collaboration in science by transforming the relatively insular higher education sector. Japanese universities, which already lag behind international counterparts for student exchange, risk slipping behind east Asian rivals such as China and Singapore.

The highest ranked institution is University of Tokyo, which is 23rd in the QS World University Rankings 2019, up six places from the previous year. The institution boasts many notable alumni including 17 prime ministers, 16 Nobel laureates, three Pritzker Prize laureates, three astronauts and one Fields Medalist.

Close behind are Kyoto University (35th) and Tokyo Institute of Technology (58th), with a further 41 Japanese universities ranked among the world’s best.

Following prompting from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development for Japan to become more involved in global innovation networks, the government introduced its Top Global Universities Project in 2014, which provides long-term financial support universities for up to 10 years, to increase the quality of their research. Thirteen top tier universities were selected for their potential to be ranked in the top 100 universities globally.

The government is also keen to attract more foreign students, setting a target of 300,000 by 2020 (roughly 10 per cent of the total student population). This would bring Japan closer to that of other non-English speaking developed nations such as France and Germany.

The most obvious obstacle to increasing Japan’s international collaboration is the language barrier. To get around this, Japanese universities are developing classes, summer courses and even full degree programmes in English. The University of Tokyo now has more than 24 degree programmes for undergraduates and postgraduates delivered entirely in English.

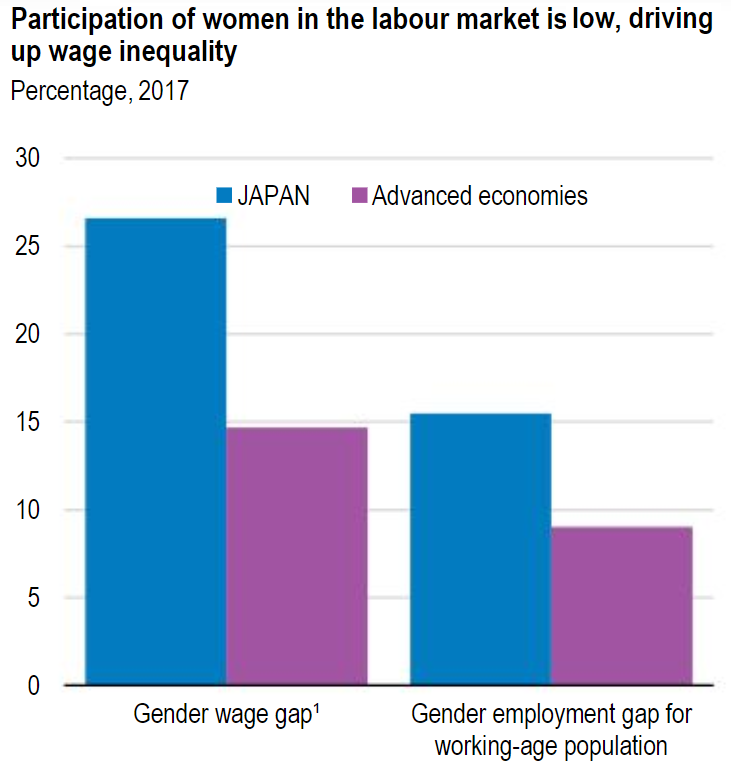

The government also wants to increase the number of women in the research workforce. Japan has the lowest ranking of advanced industrial economies on this front currently, with women representing just 16 per cent of its researchers, in the Institute for Scientific Information’s 2019 G20 scorecard.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.