There has been progress towards the 2020 targets, but EU averages hide differences in attainment between and within member states. More effort is needed, notably on basic skills, where the EU is actually falling behind its objectives

The European Commission gave out extra homework to member states that are lagging behind EU 2020 goals for education performance, calling for reforms and higher spending on education in countries with low numbers of people gaining university degrees and poor skills in reading, maths and science.

EU commissioner for education, Tibor Navracsics urged member states to spend more on education as he launched the 2018 EU Education and Training Monitor on Tuesday. “We must not be complacent,” he said.

The Monitor shows member states have made further progress towards EU 2020 education targets, but highlights the need for some countries to boost their efforts to get more people to complete higher education. “Differences between and within countries remain, showing that more reforms are needed,” the Commission said.

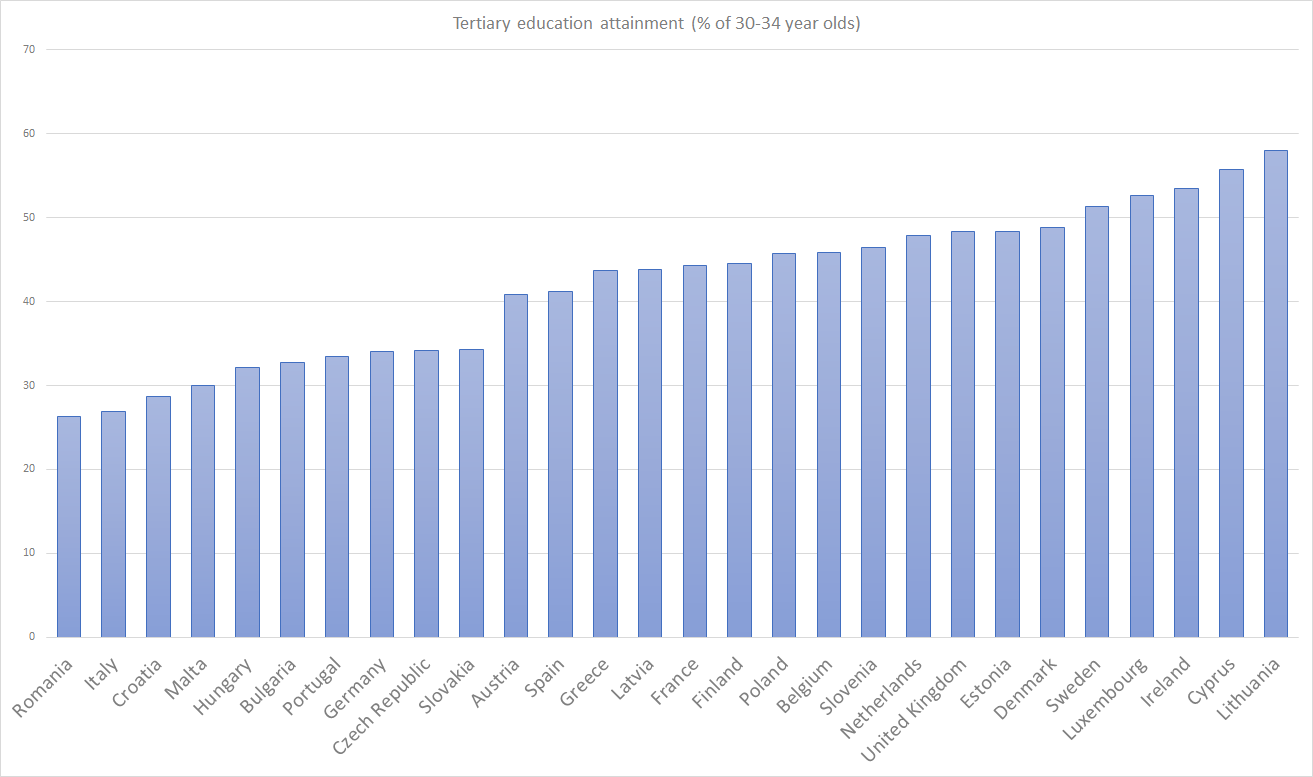

Currently, 39.9 per cent of European 30 to 34-year olds have university degrees, close to the Commission’s goal of 40 per cent by 2020.

However, in Croatia, Hungary, Spain and Finland, the share of the population with a university degree fell between 2014 and 2017. In the same period, there was “remarkable growth” in the share of the population who completed higher education in the Czech Republic, Greece and Slovakia, though neither the Czech Republic nor Slovakia has reached the 40 per cent target as yet.

In Romania only 26.3 per cent of 30 to 34-year olds have university degrees, while in Italy the figure is 26.9 per cent.

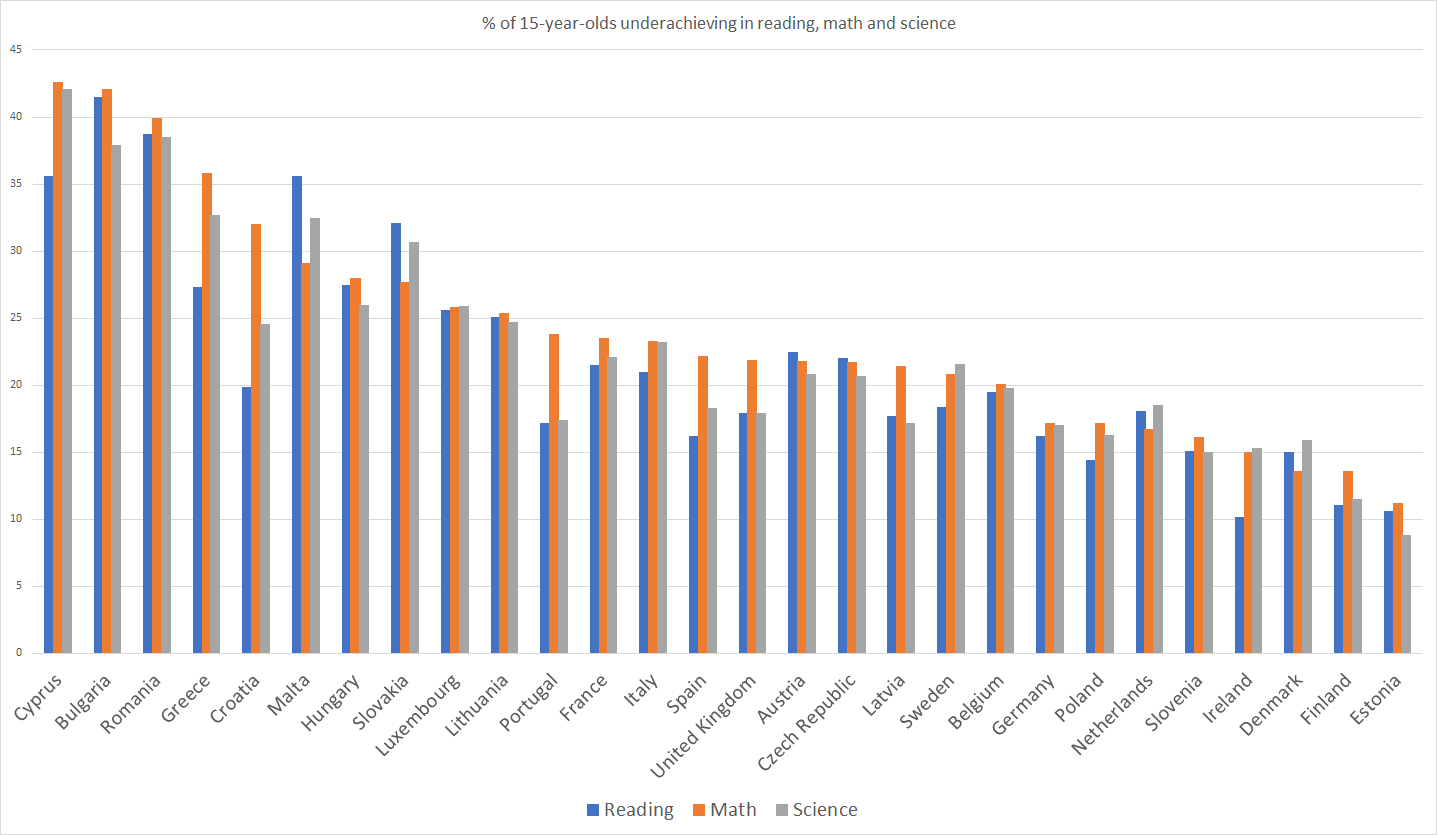

The EU also has a target of cutting the number of 15-year-old school pupils with low attainment in reading, maths and science, to less than 15 per cent.

Only Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland and Slovenia have reached this goal, while in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania about 40 per cent of 15-year-old pupils are underachieving in these subjects.

“A bigger effort is required to ensure that young people learn to read, write and do maths properly,” the Commission said.

The report shows that in 2016, education funding increased by 0.5 per cent compared to 2015. But as many as 13 member states are still investing less in education than they did before the economic crisis struck in 2008.

On average, member states spend 4.7 per cent of GDP on education, representing the fourth largest item of expenditure after social protection, health, and general public services. Overall, Europe’s spending on education is, “significantly less than the Asia Pacific area or the US,” said Navracsics.

The Commission want to convince member states to establish a European Education Area by 2025, mirroring the European Research Area, to improve national education systems. “We can and must do better,” Navracsics said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.