For years, governments have been dishing out tax breaks to induce companies to invest in research and development – but does it work? Yes, in Belgium and Portugal; not so much in France, according to a new OECD study.

For years, governments have been dishing out tax breaks to induce companies to invest in research and development – but does it work? Yes, in Belgium and Portugal; not so much in France, according to a new OECD study.

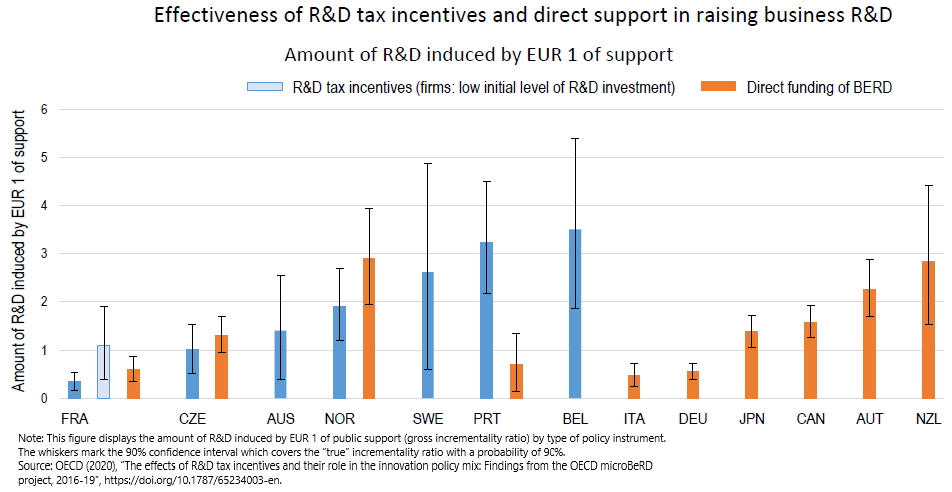

Economists at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development reported at an online conference on 14 October that, by their calculations, for every euro that Belgium or Portugal offer in corporate R&D tax breaks, they get more than €3 back in increased R&D by companies. Sweden comes close, just short of €3.

But among the countries for which the OECD obtained data, France had a relatively low return on its R&D tax breaks, getting 34 cents in extra business R&D expenditures for each euro offered in tax breaks.

The reasons are complex, but could offer policy makers a lot of suggestions on how to craft R&D policies for greatest effect. “We have to become smarter than ever in using the scientific evidence we have, in order to guide our policy choices,” said Patrick Child, deputy director general for research and innovation at the European Commission, which co-funded the study.

Across the developed world, governments are encouraging small and large companies to spend more on R&D, for the benefit of the economy overall. Currently among OECD member countries, about 55 per cent of their total public support for business R&D comes in tax breaks, with the remainder in “direct” subsidies such as grants or loans.

The OECD study gives several clues to how these tax incentives work. According to its analysis, tax breaks are most effective in spurring small and medium-sized companies, or those that don’t already do a lot of research, to spend more on R&D. On average, the 20-country study found, tax incentives for SMEs get €1.4 -worth of additional R&D activity from industry for every euro they offer in lower taxes – well above the economy-wide average of one euro in for one euro out.

By contrast, tax breaks are less effective for big companies or those already doing a lot of R&D. So France’s weaker showing could reflect the nature of French industry, with R&D already concentrated among large or established companies.

Other factors that matter, the economists found, include whether a government sets a limit on how much of a tax break is allowed; setting a ceiling on how big a benefit is possible appears actually to encourage more spending – perhaps because it means smaller companies that come under the ceiling get more of the available break.

Also, tax incentives are most effective at inducing companies to spend on close-to-market, experimental development projects rather than on early-stage basic or applied research. By contrast, direct subsidies like grants are more effective at encouraging early-stage research.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.