Researchers in Switzerland want to keep their labs as close to the EU as possible, and warn that doubts over the country’s place in Horizon Europe will strangle collaboration

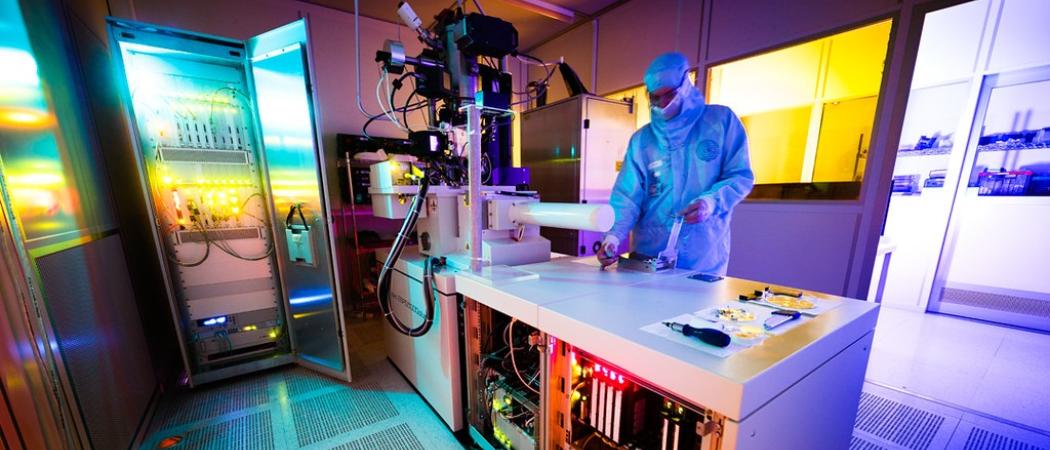

EPFL's laboratory for photonics and quantum measurements in Lausanne, Switzerland. Photo: EPFL

The prospect of a diminished science relationship between the EU and Switzerland has sent tremors through the country’s research institutes and labs, as the Swiss government walks a political tightrope with Brussels to secure a new treaty and full access to the next big EU research programme.

The political tussle playing out between Bern and Brussels, which could result in Switzerland being left of of parts of the €90 billion Horizon Europe programme running from 2021 - 2027, is worrying scientists, who are determined to be involved.

Swiss research has flourished within the framework the EU has created for collaborative science, with EU funding leading to advances in highly-specialised research fields, encouraging investment and plugging researchers into extensive research networks.

Money is the least of it, according to interviews Science|Business carried out with seven researchers carried out in Zurich and Lausanne. Testing yourself against the best in Europe, and making the connections that will take your research to the next level, is what matters most, they say.

Fear of isolation

For Tobias Kippenberg, professor of physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), reduced access to the EU’s prized research competitions from 2021 would see him take his research back to his native Germany.

“I don’t see why I should stay in isolation. If access to the European Innovation Council falls away for us, where would we be? Perhaps our start-up would have to close,” he said.

Kippenberg, who leads the laboratory of photonics and quantum measurement, is one of the university’s big research stars, winning awards for work on miniature glass oscillators that store light and vibrations. He is a serial EU grant winner – in all, one third of his funding comes from the EU, and his concerns mirror those of the Swiss research community at large, dependent as it is on long-term funding, cross-border mobility and international collaboration.

Over the lifetime of his research Kippenberg has won some 20-30 EU grants. His lab has produced the smallest optical frequency comb in existence, which may be used to improve the precision of instruments such as astronomical spectrometers or atomic clocks.

Among these grants, Kippenberg has won three from the European Research Council (ERC), the ultimate recognition for many researchers. And he has used the EU’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship programme to hire 18 postdocs. “I’m a deep believer in this programme,” he said. “You can get fellowship grants in Switzerland, but you’re maxed out after two or three.”

His field is highly specialised and as a result, “I don’t have direct colleagues here in Switzerland doing what I’m doing,” said Kippenberg. “EU collaboration means I have this beautiful network of colleagues around Europe.”

There is a quid pro quo, with Switzerland’s research helping everyone across the continent. “We’re quite wealthy; we get plenty of funding also from our university. How many other European universities are in a position to coordinate projects like we are?” Kippenberg said.

Even taking into account the 2014-2016 Swiss freeze-out from the EU Horizon 2020 research programme, the country’s researchers have received more than €1 billion in the competition over the previous six years. Barring Switzerland from EU programmes would see, “The EU lose the top groups and weaken their own projects,” Kippenberg said.

“We are also educating [researchers] for Europe and the [EU] profit[s] in many ways in return – in terms of infrastructure, for instance, we have very good support for building labs here. For every euro we get from the EU, there’s about €3 in-kind invested from the university,” said Kippenberg.

“You have PhDs and postdocs from my lab, and most of them go outside to [the rest of] Europe. I have past students and professors in places like Copenhagen, in Nottingham, in Grenoble, and one who works at Airbus.”

On Europe’s frontline

Ernst Reichmann, head of the tissue biology research unit at the University Children’s Hospital in Zurich, has developed an innovation he hopes will be adopted by hospitals all over the world.

Reichmann is co-founder of CUTISS, a spin-off company from the University of Zurich that has a laboratory process in which both epidermis and a functional dermis can be produced in about a month using cells isolated from a patient's skin and grown in culture.

“I didn’t know I would end up working in skin; originally I was a cancer researcher. All of this was a happy discovery,” said Reichmann. Skin grafts, the current standard of care to treat serious skin defects, are very often not available in sufficient quality and quantity, and frequently leave patients with permanent, painful, and debilitating scars.

“We are on the frontline with our skin substitutes and treatment. And this is not just for Switzerland – it’s for all of Europe,” Reichmann said.

The company has already been approached in two emergencies where patients’ lives were in danger because of the extent of their skin injuries. “We were asked by a clinic in Birmingham to help a young patient with severe burns. We produced 34 patches; all of these patches were [used] by the patient,” he said.

Reichmann, who was born in Germany, got his research off the ground with the help of EU funding. “Without the initial EU grants, [we] would never have achieved what [we] finally did,” he said.

Several grants later, he has learned, “It helps when people are naïve at the start. You don’t realise how much work EU projects will be, or if you can do them - but you can.”

Love of difficult start-ups

Another researcher whose invention was bootstrapped by EU funding is Mario Michan, co-founder and CEO of Daphne Technology.

Michan, originally from Columbia, where he was a serving officer in the navy and merchant ship fleet, has created a technology to purify emissions from ship exhausts.

Before taking jobs at CERN in Geneva and later EPFL, where he would grow his company, Michan was in two minds between locating in the UK and Switzerland. “In the end, I was advised that, if you want to do software, go to London, but if you want to do hardware, it’s Switzerland. People really like difficult science start-ups here,” Michan said.

The company also has a base in Sweden. “We needed naval engineers and Sweden is very good for that type of talent. Unsurprisingly, there aren’t many of them here in Switzerland,” he said.

Michan successfully applied for the EU’s EIC accelerator grant. He says any money Switzerland gets from Brussels travels back to the EU in some way. “A lot of our suppliers are in the EU, our customers are there, and we have a lot of talent that comes from Europe. In no sense can we separate ourselves,” he said.

A time machine for Europe

EPFL’s Frédéric Kaplan, a professor of digital humanities, finds the prospect of being frozen out of EU research projects “extremely sad”.

“If Europe is closing its door, this would be a terrible mistake and could lead to a progressive fragmentation of Europe itself,” Kaplan said. He runs a project called the Time Machine, which he calls, “the biggest alliance ever seen in cultural heritage.”

The goal is to build a large-scale simulator mapping 2,000 years of European history, transforming kilometres of archives and large collections from museums into a digital information system. The project, which already has had some EU funding, was recently incorporated in Vienna. Institutes like the Louvre and Rijksmuseum are on board, Kaplan says.

Many documents of the past are in private collections, said Kaplan, who is French. “There is a fight to get these into the public domain. What we have right now is only a small percentage of history in digitised form,” he said.

Having the Swiss lead this project is an advantage for Europe, he said. “It’s part of the DNA of EPFL, taking on these big European projects and coordinating them. Being Swiss has helped us a lot because we were coming with a form of neutrality,” he said.

The Time Machine is a natural way to build bridges between cultures and nations, and needs to be a European project. “We lost the web, we didn’t manage to build the social network, but we could do this. We have an opportunity to take and maintain world leadership here,” Kaplan said. “It’s Europe that has to invent the way to do this, otherwise you leave room for foreign companies to come in and commercialise our continent’s treasures.”

Compete with the strong guy

The Swiss presence in EU research programmes pushes everyone to up their game, according to Silvestro Micera, EPFL professor and co-founder of Sensars, a start-up that aims to improve the life of amputees and people with damage to their peripheral nerves. The company was founded in 2014 with two other EPFL researchers, Francesco Petrini and Stanisa Raspopovic.

Together they have oversaw the first implant of nerve electrodes in an amputee in Europe; a bionic arm enabling the recipient to feel life-like sensations in the fingers of the prosthesis. The company is also adding sensors to a bionic leg that helps below the knee amputees to improve their gait by transmitting signals from sole of the foot to intact nerves in the thigh.

Micera’s research combines neuroscience, engineering, and robotics, and Sensars has had funding from multiple EU competitions, including the Future and Emerging Technologies and the Fast Track to Innovation programmes.

Some member states may feel if Switzerland is not part of Horizon Europe, there will be more funding for everyone else at EU level. But, Micera, an Italian said, “The innovation landscape will be poorer in the long term. Getting rid of the champions makes people weaker. You want to compete with the strong guy, not get rid of him,” he said. “If you do that, how do you think you’re going to match up to what the Chinese and the US have to offer?”

We are in demand

At IBM Research in Zurich, Bert Jan Offrein is developing neuromorphic devices that learn in the same way as the brain. These will be used to train neural networks to be more adept at image recognition. “They are becoming more and more important for image recognition; standard computers have quite some difficulty with this,” Offrein said.

Substantial funding for this work comes from the EU. That money helps the lab hire PhDs and postdocs. “We act like a university in this respect,” Offrein said.

Offrein and his team are involved in several EU projects, such as Neurotech, creating a communication channel between companies and research institutes operating in the field, like ETH Zurich, Manchester University, Thales and Belgium’s IMEC lab.

“Being strongly embedded in this technology is important for Europe,” he said. “In terms of tech, Europe is strong; in terms of turning it into actual products, we need to improve.”

His team “are getting a lot of requests to participate in European projects. We are perceived as a valuable partner,” said Offrein. “In the end, this is an ecosystem, and we are a very important part of it. We must absolutely be sure we can stay in this ecosystem.”

Quantum dream

Across the city, Tilman Esslinger, a German experimental physicist and a professor at the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH Zurich, talks of the buzz he gets from writing EU proposals. “It’s always inspiring. The openness and the width of competition is unique,” he said. “It’s not political; it’s just about good science.” Unlike the US, Europe doesn’t have big tech companies working in quantum, so it compels everyone to work together, Esslinger said.

Esslinger also praises the EU’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship programme. “This is the best we have; you’re always so sorry for the people you have to turn down; there’s too few places available.”

He is on his second ERC grant. “Everyone outside Europe is jealous of this programme and how it gives us first class science,” he said. The grants have allowed Esslinger to take his research in “freewheeling directions.” With the latest grant, he aims to find out how matter, heat or magnetic orientation get from point A to B.

“The Swiss are bringing the very good research. We were first in Europe, and maybe also in the US, to have a quantum engineering master’s programme. We were fast and we should keep the spirit to be fast,” he said.

EU research will suffer without the Swiss or the Brits, Esslinger believes. “If you close the door on Britain and Switzerland, there’s a lot less left in Europe,” he said. “You cannot take them out of the ERC and have the same level.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.