Construction of the Square Kilometre Array radio telescope faces some lockdown delay, but the science continues as normal

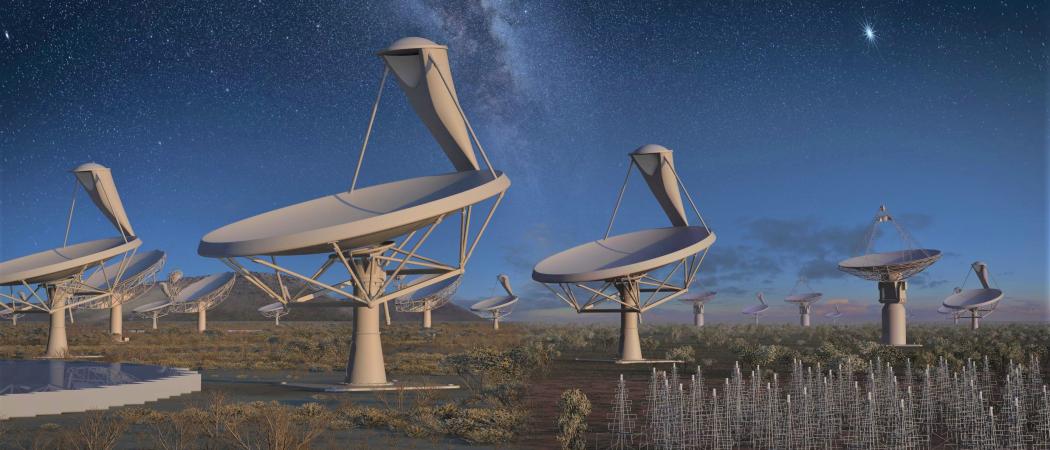

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) at night. Photo: SKA.

Construction of the giant Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is likely to be delayed by several months, with COVID-19 lockdown measures making some tests of prototype equipment impossible, and parliaments slower to ratify the intergovernmental convention governing the building and operation of the radio telescope.

Nine years after it was agreed SKA would be split between sites in South Africa and Australia, building the telescope was due to start in January 2021. But last week Philip Diamond, director general of the SKA Organisation, said COVID-19 enforced delays mean the project is now aiming for, “commencement of SKA1 construction activities as early in 2021 as possible.”

Diamond hopes the delay will be minimal. “If it’s two or three months, we’ll count that as a success,” he said. SKA’s headquarters at Manchester University’s Jodrell Bank Observatory where Diamond is based, have now been shut down for more than six weeks. In an update last week, he said, “It is my expectation that the shutdown will continue for some weeks yet.”

A few months looks like marginal in terms of the time frame for the project, with SKA not due to be fully operational until 2030. Once complete, the telescope will have the capacity to look back in time to the first billion years of the universe and the formation of the first stars and galaxies.

That will be achieved by combining data from a collection of large antennas spread across remote areas of South Africa and Australia. The €1.8 billion international project also involves Spain, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, China, Canada and India, amongst other countries.

Scientific work continues

“Construction-related activities have temporarily stopped,” said Rob Adam, managing director of the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO), which manages the country’s role in SKA and also operates MeerKAT, the world’s biggest radio telescope and one of two SKA precursor instruments. However Adam said, the pandemic, “has had almost no impact whatsoever on our science operations,” which are, “continuing as if there was not an epidemic.” That’s because SARAO is used to remote working, since mobile phones, microwaves, laptops and cameras can all interfere with the equipment.

At the beginning of April SARAO was given the job of managing South Africa’s national ventilator project for the local design, development, production and procurement of ventilators for COVID-19 patients who need oxygen therapy. The mandate is based on the experience SARAO gained in the development of systems for MeerKAT.

Four senior engineers working on SKA in South Africa have been seconded to run the ventilator project. “But their teams are still in place and helping us with the design activities, the analysis of data, and things like that,” said Diamond. Employees are working from home and meetings take place virtually. That would have been much harder a decade or so ago. “The technology is allowing us to do this,” Diamond said.

Not only is scientific work continuing, the SKA partnership has grown under lockdown, with École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) joining at the beginning of April as the lead institution on behalf of Switzerland. “All of that paperwork was signed off in the last few weeks, amidst the lockdown,” said Diamond.

But with everyone in isolation, hard copies had to be mailed from one person to another for signatures, which took weeks, said Jean-Paul Kneib, professor of astrophysics at EPFL. He said EPFL will work with other Swiss institutions and companies to contribute scientific expertise and technology, such as atomic clocks. The Swiss government is expected to commit CHF 9 million (€8.5 million).

Minor maintenance

The work that is suffering is on-site prototyping and maintenance. “There are points where you have to physically test things, where you have to get out and do stuff on the ground, and that’s been held back a bit,” said Adam. Some minor maintenance is still possible. “But you can’t bring teams; you can go one person at a time to do a reset of an antenna,” he said. “Of the 64 antennas, we’ve usually got more than 60 working, the rest are in some form of maintenance. At the moment we’ve got 59.”

Like many countries, South Africa has imposed a strict lockdown and travel is severely restricted. That’s a challenge, given MeerKAT is about 90km away from the nearest town. SARAO can get travel permits, but there are bureaucratic hurdles. “If there’s a roadblock, you’ve got to wave the permit in front of a law enforcement officer and hope that he actually agrees that this is a proper permit,” said Adam.

Delays to treaty ratification

The other problem is passing legislation. Currently, the project is led by SKA Organisation, a non-profit UK company. That is due to transition to SKA Observatory, an intergovernmental organization, along the lines of the body that runs the CERN particle physics laboratory in Geneva, during 2020. The treaty will enter into force once host countries South Africa, Australia and the UK, have ratified it, along with two other signatories.

Diamond said ratification will be delayed because parliaments preoccupied with COVID-19 are not meeting face-to-face and the bureaucratic wheels have slowed. Only Italy and the Netherlands have ratified so far. Besides them and the three host countries, China and Portugal are also signatories. Switzerland currently is not, despite government backing for EPFL’s involvement.

Given the impact of lockdown measures on the world economy, tax revenues are likely to fall, raising the question of how much governments around the world will be prepared to spend on the SKA.

In South Africa’s case, SARAO’s budget is set by South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation, and will cover half of the R800 million (€40 million) cost of building 20 new antennas for the SKA by the end of 2022. The other half is due to come from Germany’s Max Planck Society. Adam is confident that the funding is secure. “In South Africa, there’s such a strong commitment to the overall SKA that’s been made from the early days,” he said. “I think that there would be a tolerance towards the situation, which is beyond our control. I think that we would be accommodated.”

Another lingering question is what international science projects like the SKA will look like once the COVID-19 crisis is over. Adam said travelling is “almost a badge of pride” among scientists, showing “they’re needed and wanted in other places.” If a scientist can’t demonstrate lots of travel in grant applications, "people kind of wonder about you.” But the pandemic makes him and his colleagues wonder, “do we travel too much?”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.