In a country where petrochemicals are king, the government is making a studied effort to send the economy off in more sustainable, long-term directions

Norwegians have long explored and lived off the sea. Stands to reason, then, that the country’s most successful businesses and scientific communities originate from settlements along its breathtaking coastline.

Norway's ocean is the basis for one of the world’s largest seafood industries, as well as a large maritime industry and growing renewable energy industry.

The waters around Norway contain vast stores of oil and gas, which have made the country one of the wealthiest in Europe, and one of the biggest fossil fuel producers and exporters in the world.

That the economy should still be so involved in oil and gas is now being treated as a political problem to be fixed. The government says it wants to make Norway a low-emission country by 2050, by reducing emissions by 90–95 per cent.

Most of the political muscle, then, is going into speeding up Norway’s shift to renewables. Since 2014, the government has launched a number of “clusters” promoting startup innovation.

The most important tool for ensuring good coordination and implementation of research, innovation and higher education policy is the government’s Long-Term Plan, which runs to 2024.

Three headline objectives underpin this strategy, which is up for renewal every four years: strengthening competitiveness and innovation, meeting major societal challenges, and developing skills to match changing demands. The core, long-term priorities remain with developing industries around the ocean, but also in climate, the environment and environmental-friendly energy.

Want to buy an electric car in Norway? The government waives the high taxes it imposes on sales of other cars. The country’s major fossil fuel companies, meanwhile, are starting to back renewables in a big way. The nation now sources most of its electrical energy from water, and hydro-electric power stations dot the mountainous and windy Norwegian landscape. Short-distance electric ferries navigate the coast, and floating wind turbines bob along farther out to sea.

An early indication that the country’s efforts at diversification are paying off can be found in the EU’s annual Innovation Scoreboard. In the last two years, Norway has improved its standing in the Brussels league table, jumping from a ‘moderate innovator’ to a ‘strong innovator’ (though falling short of hitting the top tier ‘innovation leader’ rank).

Who are the research and innovation players?

Public funding for research and innovation has grown over the past decade, with a particularly strong surge coming between 2013 and 2016. During this period, growth was stronger for industry measures than for basic research.

The three major players in research and innovation are the Research Council of Norway, Innovation Norway and Skattefunn (an R&D tax incentive scheme, which has become one of the largest sources of innovation support funding).

In recent years, innovation spending from these three taken together has risen substantially, driven mainly by the growth of Skattefunn. Another agency, Enova, was set up in 2001 to test, demonstrate and promote new energy solutions.

Innovation Norway runs under the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries and (counting loan schemes), the agency contributed NOK 7.2 billion (nearly €1 billion) to Norwegian businesses in 2018.

The Research Council comes under the Ministry of Education and Research and last year it invested NOK 9.8 billion for research and innovation. The council specialises in basic research as well as R&D. It runs large-scale technology demonstration programmes and builds up R&D capacity, not only in universities and institutes, but also in companies.

The council has also done a lot of policy coordination across the ministries. This wide-ranging policy brief seems normal to Norwegians, but places the funder apart from standard international funding practice.

Norway’s role in EU research: slowly growing

Participation in EU research programmes is the main plank of Norway’s international research policy, and is secured by dint of the country’s membership of the European Economic Area.

As an ‘associated country’, Norway has limited ability to influence the direction of European research funding. However, it does engage extensively in EU-funded research, contributing to, and receiving funding from, EU Framework Programmes.

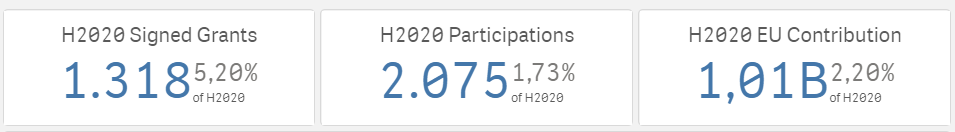

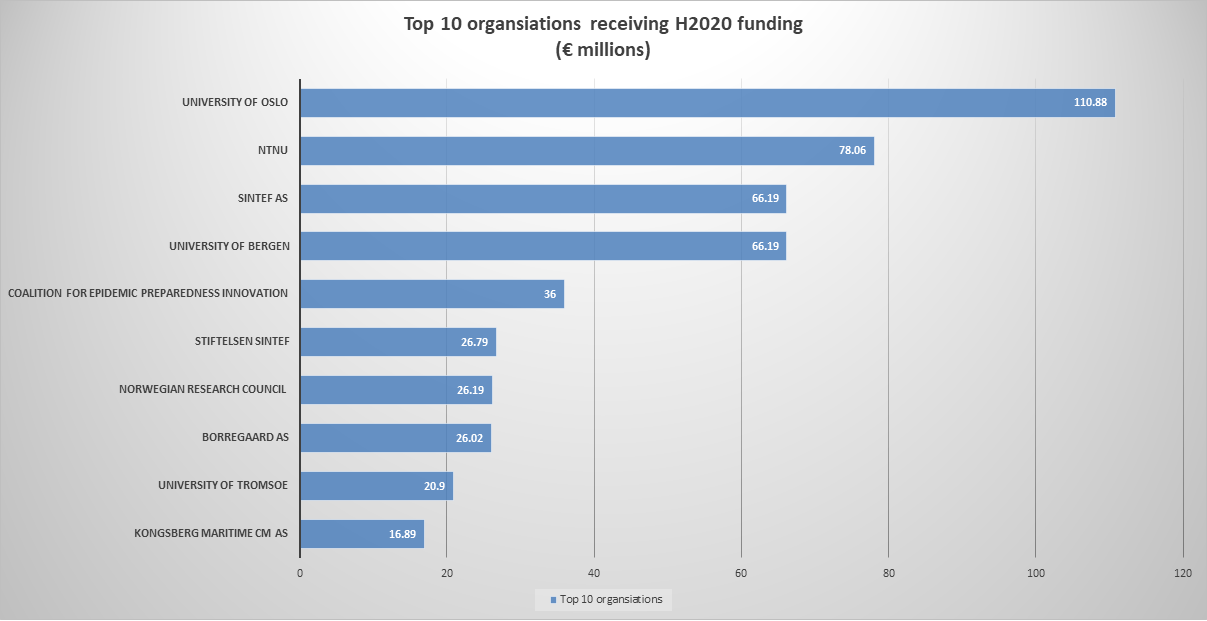

In 2014, the government saw the need for action, as the country’s share of EU monies dipped to 1.67 per cent. A strategy was launched the same year to kick Norwegian participation back up to 2 per cent. The push yielded results, with the country’s return share today at an all-time high (2.2 per cent).

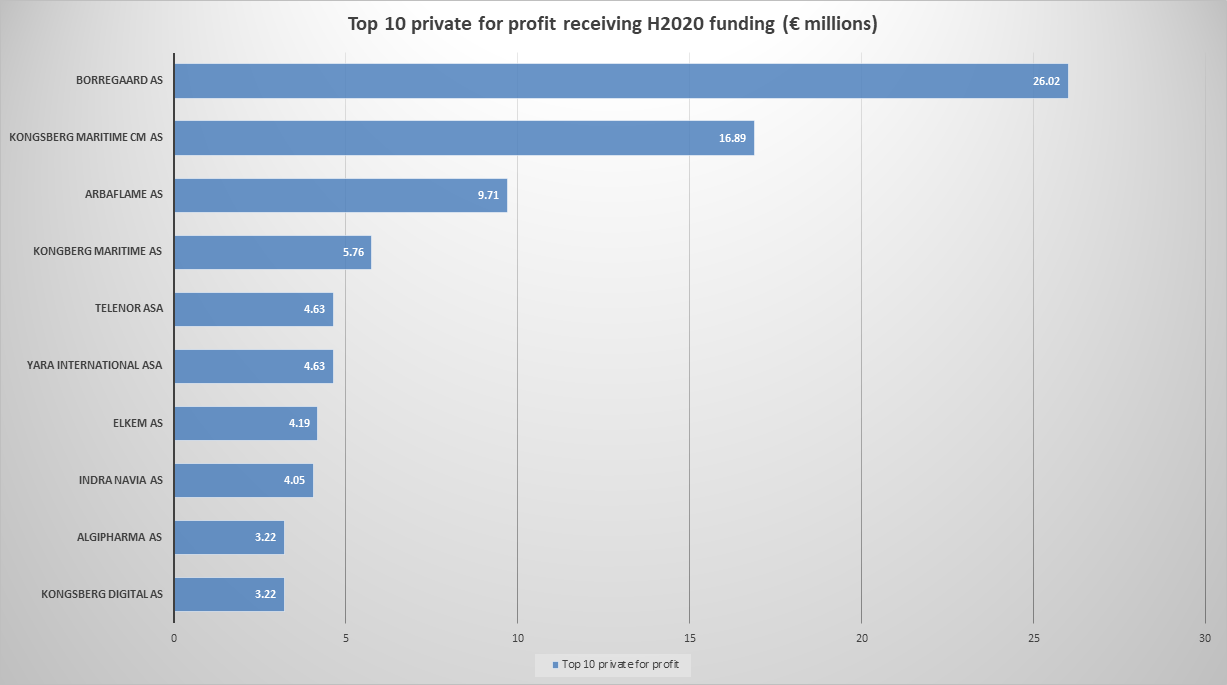

EU funding has gone to Norwegian companies such as Oslo-based Airtight, which promises to reduce energy leaks in buildings by 50 per cent. Brussels has also backed Piql, which offers long-term digital data storage, and Glucoset, which has developed a sensor for continuous and safer measurement of blood sugar to critically ill patients during surgery.

As for fundamental science, Norway accounts for around 1.5 per cent of overall European Research Council applications, placing it in the top quarter of applicant countries (of a similar size).

The overall success rate of Norwegian applications to the EU funder has been just over 8 per cent, compared with an all-country average of over 11 per cent.

The main universities

A recent Technopolis analysis concludes that Norwegian research is generally good but doesn’t contain many ‘peaks of excellence’.

Norway has five universities that feature on the 2019 Times High Education ranking of world universities list. However, none of these breach the top 100.

The top five Norwegian universities:

- University of Oslo – 121

- University of Bergen – 197

- Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) – 351-400

- The Arctic University of Norway – 401-500

- Norwegian University of Life Sciences – 501-600

The ranking scores universities on teaching, research, knowledge transfer and international outlook. The universities of Oslo, Bergen, and NTNU have climbed the ranking from the previous year (these universities make up the bulk of Norwegian applications to the European Research Council). Not on the list is the University of Tromsø, which has the distinction of being the northernmost university in the world (a good place, then, to study the Arctic Circle).

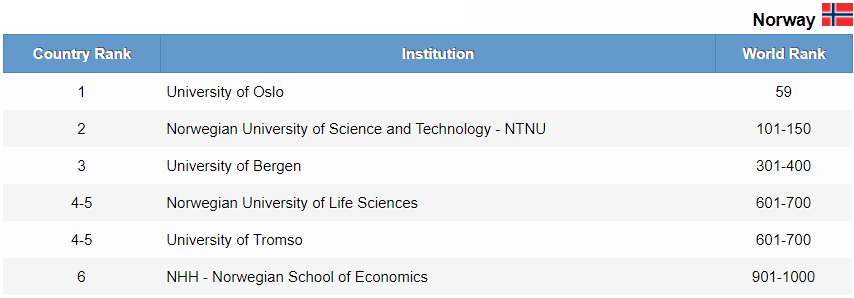

If you look at the Academic Ranking of World Universities published by the University of Jiaotong in Shanghai, however, the picture looks a little different. In this ranking, Oslo university, the producer of four Nobel Prize winners and the best Norwegian entry, scores at number 59.

The ranking scores universities on things like number of alumni and staff winning Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals, number of highly cited researchers, number of articles published in journals of Nature and Science (and takes into consideration university size).

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.