Scientists warn of delays to transatlantic health collaboration after the US ends a key funding mechanism citing “national security”

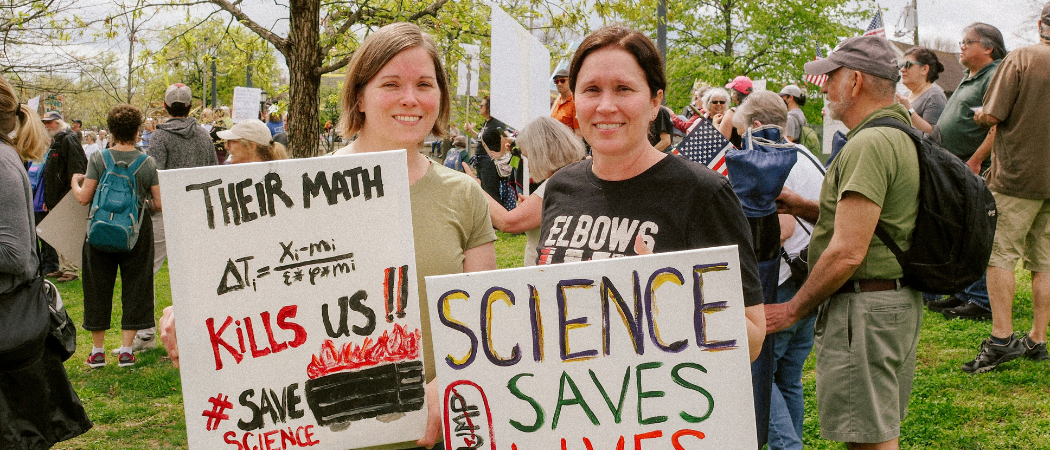

Photo credits: Barbara Burgess / Unsplash

The shock decision by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to stop new funding for more than a thousand foreign research partners is causing delays and uncertainty in global health science projects, say scientists.

While many researchers in Europe are still scrambling to understand exactly how the policy will impact their collaborations with the US, it’s already caused some projects to slow down.

“It’s going to cause delays,” said one researcher at a UK university, who is a part of an NIH-funded rare disease project. His university, sceptical that the NIH will deliver on previously promised funding, has told him to hold off hiring a researcher for the project until there is more clarity.

“I can’t employ anybody,” said the academic, who did not want to be identified, “which will affect timelines.”

The NIH decision, announced on May 1, halts the payout of new grants to projects that involve foreign sub-awardees. These are foreign research institutions sub-contracted to help perform data analysis, provide patient data or contribute other expertise, for example. NIH awards directly held by foreign researchers are unaffected.

A “lack of transparency” for sub-awards and a “need to maintain national security” led to the decision, according to the agency.

Although the NIH doesn’t mention it explicitly, the agency’s sub-awards system became controversial following the pandemic, when it emerged that the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a suspected but never proven possible origin site of the COVID-19 virus, was a sub-awardee on an NIH project studying coronaviruses.

However, this latest policy goes far beyond tightening conditions on potentially risky virus research. Instead, it targets all foreign sub-awardees, risking collaborations that need patient data from multiple countries, or that study tropical infectious diseases, for example.

“For a lot of clinical research, there's a challenge getting enough patients to study,” said Philip Rosenthal, an infectious diseases expert at the University of California, San Francisco. Adding EU patients to a US cohort “dramatically increases the number of patients you can study,” he said.

The future of Professor Rosenthal’s own NIH-funded projects in Uganda is now uncertain. “We're having hard conversations about, do we need to lay off personnel who work with our programme?” he said. “That is so devastating.”

New system

The NIH said it will create a new grant tracking system by the end of September, to “ensure it can transparently and reliably report on each dollar spent.”

However, even after that, the sub-award system that allowed money to flow down to foreign researchers will not be re-instated. Instead, foreign researchers who augment NIH projects will need to hold direct, individual awards from the NIH.

“We are encouraging applicants reapply with subproject structures,” said David Kosub, senior health science policy analyst at NIH. “Implementing this structure allows these activities to undergo NIH’s scientific review process, be tracked in the same database as NIH grants, and be governed by direct terms and conditions with NIH," Kosub added.

It’s unclear exactly what this new tracking system will mean for foreign researchers in terms of application and reporting paperwork. But some European researchers are worried it could introduce extra bureaucracy.

"It seems to me that this will generate more, and largely redundant, paperwork without any actual benefit,” said Ethan Weed, a linguistics researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark, who is a sub-awardee on a project led by the University of Connecticut looking at conversation in autistic teenagers.

Foreign collaboration using NIH funding could therefore become "much less appealing," he said, even though he doesn’t expect the recent policy change to affect his own project.

What’s more, the "capriciousness" of the US government's changes would make potential foreign collaborators think twice before committing to NIH projects, said Weed.

"Early career researchers such as PhD students and postdocs move across the globe, delay having children, and generally uproot their lives in order to take the positions that are funded by programs like the NIH," he said. "It is absolutely critical that they and the researchers who hire them can rely on this funding not disappearing at the drop of a hat."

Related articles

- Trump halts new NIH grants to international health-research partners

- Data corner: which fields of health science is the US curbing?

- NIH turmoil risks reciprocal EU-US access to health research funding

Dimitris Rizopoulos, a biostatistician at Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam, said the policy change would mean that future plans with US partners “cannot be realised anymore,” although his ongoing projects would not be affected.

Other European sub-awardees who spoke to Science|Business said they were still trying to work out how the changes would impact their projects.

“There is a lot of uncertainty on this topic,” said Antonio Gonzalez, a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council, who is collaborating with Cornell University on high performance brain scanning.

EU reciprocity

Unusually, Brussels allows US researchers to win funding from Horizon Europe’s health cluster, as a kind of unofficial quid pro quo for European researchers being able to receive money from the NIH.

But with the NIH clamping down on foreign sub-awardees, and cancelling projects that mention politically forbidden terms related to diversity, equity and inclusion, the future of this arrangement is unclear.

“The European Commission is following the developments very carefully,” said Thomas Regnier, its spokesperson for technology sovereignty, defence, space and research, in response to the NIH’s new sub-awardees policy.

“Research is a global endeavour in which no talent should be wasted,” he said.

NIH turmoil

The end to sub-awards is only the latest major policy change at the NIH since Donald Trump became US president in January. Hundreds of existing grants have been cancelled, primarily targeting studies of transgender people’s health, racial bias and HIV.

The agency has also cut the amount of money universities can claim back for the indirect costs of research, such as lab space. More than 1,000 NIH staff have also been fired.

In addition, the White House has published plans for a 40% cut in NIH spending, alongside a 55% cut for the National Science Foundation, although this must pass through Congress first.

Editor's note: This article was updated 16 May 2025 with comment from NIH.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.