EU’s poorest country is the exemplar for why national systems need fixing before there is any preferential treatment in Horizon Europe. As things stand, more funding for R&D in Romania would be ‘money thrown out of the window’

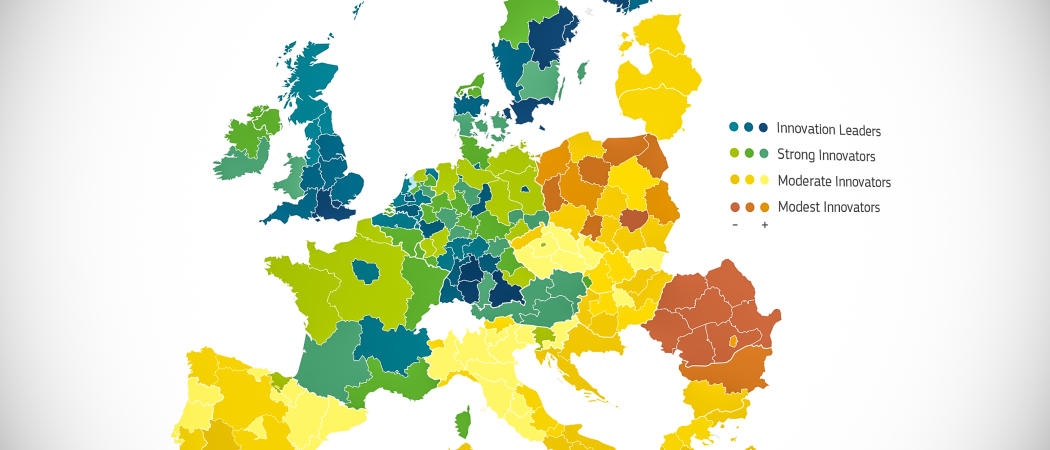

According to European Commission's innovation scoreboard, Romania has some of the least innovative regions in the EU

Romanian researchers and R&D experts have hit out at the ‘Europe first’ vision of Romanian MEP Dan Nica, saying that before attempting to introduce quotas into Horizon Europe, politicians should first find ways to make the research system at home fairer and more competitive.

Nica, the co-rapporteur helping to steer Horizon Europe through the European Parliament, says his proposals will strengthen EU’s position against other global scientific powers, while helping poorer member states get more out of the EU’s research purse and catch up with their richer counterparts in north western Europe.

Critics say that while Nica’s proposals may be well-intentioned, they show a lack of thoroughness. “Mr. Nica doesn’t understand the mechanisms of research funding,” says Daniel David, pro rector for research at Babeș-Bolyai, Romania’s largest university.

The current EU research programme, Horizon 2020 accounts for only a fraction of the total EU R&D expenditure, with the majority of funding coming from national governments and businesses. “The programme is not a social programme to bridge divides,” David says. Rather, the answer lies in greater national spending and a more tactical application of structural funds to build research infrastructures.

“Probably Mr. Nica and I understand things differently,” says David, who views Horizon 2020 as putting Europe first in the sense that it aims to attract leading researchers from outside Europe to the EU’s benefit. “I absolutely agree with “Europe first” but in the sense that we bring in the best to the EU,” he says. “Horizon Europe should keep full throttle on excellence.”

Nicolae Zamfir, the director of the EU-funded laser facility, Extreme Light Infrastructure, the largest research infrastructure in central and eastern Europe, told Science|Business that Europe first is “a very good idea.” However, that does not mean the EU should discourage the exchange of ideas with other scientific powers, even while at the same time acknowledging Europe it is in competition with them. “Science is global,” Zamfir says.

Using Horizon Europe to reduce the research and innovation gap in Europe is “a very good idea, but it must be carefully presented, so it is not at odds with the principle of excellence,” says Zamfir.

Research and higher education in central and eastern Europe should be supported financially, enabling research infrastructures catch up with those in north-western countries. “That cannot be done without funding,” Zamfir says.

Authors of their own misfortune

Other researchers say that central and eastern European countries are to blame for their own misfortune. Frequent changes in policy and leadership in research had “a fantastic impact,” says Mihai Miclăuș, a genomics researcher at the Institute of Biological Research in Cluj-Napoca.

Suggesting that researchers should live and work wherever they are born will not solve anything, says Miclăuș. He blames the dismal situation of Romanian research on the “incompetence” of the research ministry and frequent changes at the top of the government. “Agendas are shifting on the go,” he says.

David agrees, saying to fix things, Romania needs to “ensure research competitions are predictable” and that there is “harmonious development” of R&D infrastructure.

Romanian officials in Bucharest and in Brussels have not answered repeated requests from Science|Business to comment on Nica’s proposals for Horizon Europe and the objectives for research and innovation policy in Romania’s rotating presidency of the EU Council.

The upcoming presidency of the EU council will put Romania at the helm of negotiations over EU’s €100 billion research programme. It could present an excellent opportunity to work with all member states on policies to bridge the EU’s innovation gap.

But the preparations for the role have been marred by confusion and high-level resignations.

Research minister Nicolae Burnete resigned in August without giving a clear reason, while EU affairs minister Victor Negrescu has also resigned just six weeks ahead of the Romanian take-over of the EU Council presidency.

Burnete has since been replaced by chemical engineer Nicolae Hurduc, who has not made known his strategy for Romania’s EU presidency. Romanian political infighting has seen six research ministers come and go since 2016.

For now, the government seems preoccupied with its spat with Brussels over the rollback of anti-corruption legislation. The European Parliament recently voted through a resolution against changes made to Romania’s judicial system, while the Commission has postponed Romania’s accession to the Schengen area indefinitely.

Under these circumstances it is unclear if Romanian statecraft is up to winning the trust of its fellow member states and persuading them to back a research and innovation programme that is focused on reducing the innovation gap.

Fix the national R&D system first

In addition to its political turmoil, Romania has a series of negative records in research and innovation. Compared to the rest of the EU, it has the lowest R&D expenditure, at only 0.48 of GDP, the lowest number of patents per capita, and it comes last in the Commission’s innovation scoreboard.

Despite this underinvestment, earlier this year the government proposed cutting €26 million off the 2018 R&D budget of €350 million. The cut is part of a wider rejigging of the budget, which saw an additional €25 million being allocated to the Orthodox Church.

“Little money, poorly managed,” is how David describes Romania’s research funding dilemma. The first step towards a more effective research system would be to put the available money into competitive areas at a regional level, so that these national pools of excellence can compete internationally.

Right now, David says, Romania’s research funding system “gives out poverty and we take back poverty.”

Some national research institutes, including the institution where Miclăuș works, had to half work shifts for scientists because projects had not been approved on time and competitions were delayed. Researchers working in these institutes rely on project-based funding that often comes with long delays. They do not have a base salary to start with, which also affects the salary levels they can budget in EU-funded projects. “If we had base salaries, that wouldn’t be the case,” says Miclăuș.

In 2017, minister Lucian Georgescu kicked off competitions for which consultations were open for only four days. Georgescu also insisted on using only national experts to evaluate research projects. These national evaluators were allowed to compete in the same competitions, provided that the projects they submitted are not in the field they are expected to evaluate.

According to Miclăuș, that puts the competitiveness of national funding under a big question mark. “Of 65 national research institutes, none are evaluated by foreign experts. “We should give up on national evaluators,” Miclăuș said.

Universities are also facing funding difficulties. According to David, the Romanian government should figure out better ways to support researchers and research infrastructures in universities. “We do not have money to hire researchers on indefinite period contracts.”

David also decries the uneven development of R&D throughout the country. “It is not normal that all big infrastructures are in the south.” Structural funds can be used to fund a harmonious spread of research capacities, but David believes that structural funds are “wasted in areas of political interest.”

Fake PhDs and delayed payments

To reinstate the credibility of its research system, Romania also needs to reassess the quality of many PhD programmes. As revealed by Nature in 2012, former prime minister Victor Ponta copied large parts of his 2003 doctoral dissertation on international criminal law, without proper citation.

In her 2017 book “The Doctorates Factory”, investigative journalist Emilia Șercan widely documented that certain academic institutions offered tens of PhD degrees to political acolytes. Earlier this year, Șercan attended the doctoral viva of former education minister Liviu Marian Pop and brought forward evidence that Pop had plagiarised large parts of his dissertation on migration and national security. The evaluation committee immediately suspended the session and Pop is now awaiting a decision on his case.

These deficiencies illustrate that increasing public R&D spending would be pointless unless “we clean up the system,” said Miclăuș. Under current conditions, “spending more on research means money thrown out the window,” he said.

In addition to weakening its national research system, frequent government changes have also put Romania’s membership in the European Space Agency (ESA) at risk. The ESA allegedly suspended Romania’s voting rights over unpaid contributions worth €50 million, a decision that has affected ESA-funded projects in Romania. An ESA spokesman declined to comment and told Science|Business to ask Romanian authorities about this, but the government has not responded to a request for comment. It is still unclear whether the issue has been resolved.

Miclăuș says that many of his Romanian colleagues working abroad want to move back or at least to work part time in Romania, but the lack of funding stability and transparent competitions is a strong deterrent.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.