The seal of excellence is as much a signifier of the EU’s R&D funding shortfall as it is of Europe’s high quality science. Now, the EU wants money from the cohesion programme to fill the funding gap and translate research to market

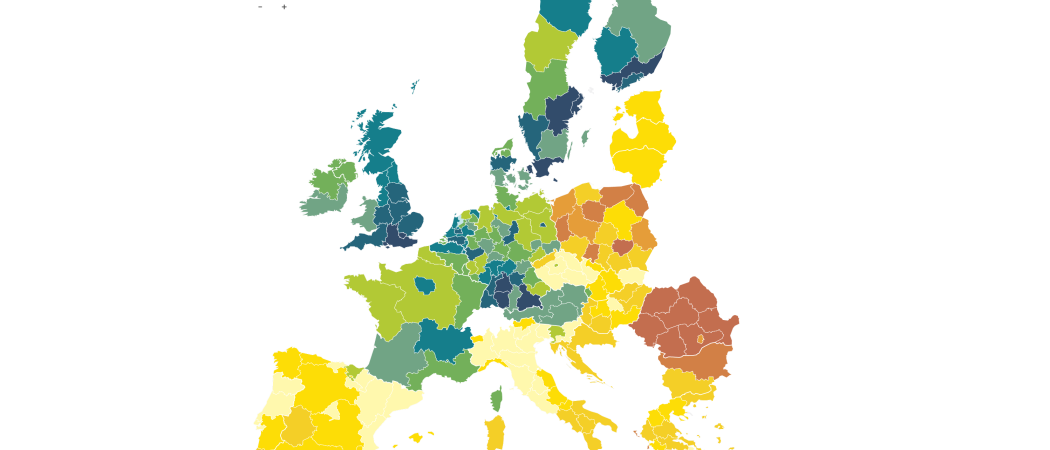

Innovation performance is not spread evenly across Europe's regions

Just a couple of years into the Horizon 2020 R&D programme, the European Commission was forced to conjure up an instant fix for a large and embarrassing problem: pitifully low success rates. With national governments having cut their research budgets, competition for grants was intense and some competitions, such as the SME Instrument, had success rates of less than 10 per cent. In fact, companies applying to phase 2 of the SME Instrument had a success rate of only 5.5 per cent.

The fix the Commission came up with was to use other funding streams to support projects that receive high marks in evaluation, but do not make the final cut because of limited budgets.

In 2015, the Commission launched the “seal of excellence”, a high-quality stamp for projects submitted to Horizon 2020 that were considered worthy of funding, but did not get it. The Commission hoped researchers and innovators could to use the seal to get access to structural funds. It was also thought this was a route to help reduce the gap in science and innovation between eastern and western member states.

In the event, the seal of excellence has helped channel the structural funds to several projects, in Spain, Italy, Cyprus, the Czech Republic and Poland. But it has not been a huge success. Despite a few positive results, the seal of excellence is “a big flop” in central and eastern Europe, according to one EU official.

One reason for the failure is that most structural funds are allocated to regions where few projects have won the seal of approval. This has led to some governments to ask the European Commission to award the seal to projects which were close to meeting the quality threshold of the EU evaluators.

Finding other funding sources

Czech company NenoVision was among the first to receive a seal of excellence in 2015, which it was able to use to obtain funding through SME Instrument Brno, a regional project of the South Moravian Innovation Centre that uses structural funds to finance recipients of the seal.

This alternative funding allowed NenoVision co-founder Jan Neuman to get the product, for increasing the capabilities of electron microscopes, to market quickly, but he had to also rely on other funding sources. The SME Instrument Brno programme offers only up to 57 per cent of the total eligible costs, while Horizon 2020 projects can get 70 per cent cash in hand.

After three attempts to be selected for the first phase of the Horizon 2020 SME Instrument, Spanish biotech company Neoalgae was awarded the seal of excellence. That gave the company access to national funding for a feasibility study and it subsequently applied for the second phase of the SME Instrument, but the project fell under the funding threshold twice.

A second seal of excellence opened the door to other opportunities and the company was able to attract investors and to find a partner in the cosmetic industry. “Together we applied again for SME Instrument phase two and won,” said director Fidel Delgado.

Most recipients of the seal of excellence prefer to reapply for Horizon 2020 grants instead of pursuing structural funds through their governments. That is mainly because national authorities that manage structural funds usually offer around 50 per cent financing, while Horizon 2020 offers 70 per cent cash in hand.

Under Horizon Europe, the EU’s next framework programme for research and innovation, the seal of excellence will still be sugaring the pill of low success rates. “Both ERC and Marie Curie action are seriously oversubscribed,” Patricia Reilly, deputy head of cabinet of EU commissioner Tibor Navracsics told delegates at the Smart Specialisation and Technology Transfer as Innovation Drivers for Regional Growth conference in Sofia on May 3rd.

New budget, new ideas

In its budget proposal for 2021-2027, the European Commission has cut seven per cent from the cohesion programme, which exists to help reduce economic and social disparities across the EU. But, according to the proposal, the new structure of the budget will enable “more efficient links with other EU programmes” to ensure that investment in roads and railways is coordinated with other EU investment in research and innovation.

The plan is to have Horizon Europe supporting scientific excellence, with the EU cohesion policy translating research outputs to the market. “We have all that mingled nicely together through cooperation and synergies,” Charlina Vitcheva, Deputy Director-General at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) told delegates at the conference in Sofia.

The proposed cut to the cohesion funds was immediately met with scepticism, with members of the European Parliament the first to express their alarm. “Ask the member states if they agree to cutting agriculture and cohesion funds,” said José Manuel Fernandes, a member of the Budgets Committee in the Parliament.

Some member states are unhappy that there will be less money to go around because of Brexit, but there is also agitation amongst richer member states which are net contributors. These countries, “Want to see more value for their money,” said Reilly.

The Commission says that the new budget opens the way for more of the cohesion budget to be spent on R&D projects holding a seal of excellence. In addition, EU regional funds might be made available directly from national authorities, a move that “will short-circuit an awful lot of administration for applicants,” said Reilly.

The EU will also continue its smart specialisation programme, under which regions are encouraged to play to their strengths and specialise and innovate in well-defined areas.

The Commission has tied the availability of structural funds for regions to their smart specialisation strategy. Smart specialisation strategies, “used to be an ex-ante conditionality for using structural funds,” The Commission will maintain this approach after 2020. “It will continue,” said Vitcheva.

Changing the innovation mindset

Europe should not expect a “massive shakeup” of synergies between different funding programmes for innovation, according to one EU official. Synergies for the sake of synergies are not the best way to plug Europe’s innovation gap. Instead, the EU could encourage member states to change their systems and organise more competitive calls, including the use of foreign experts to evaluate grant applications.

Italy and Latvia are using foreign evaluators for structural funds, and this is having a positive impact on managing innovations coming from SMEs. More countries will need to join them and modernise their approach towards innovation, if synergies between EU’s funding programme are to have the desired impact.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.