Stakeholders are urging the European Commission to improve regulations and funding mechanisms for research infrastructures. It is not enough to fund their construction, operating costs must be covered to ensure long term viability

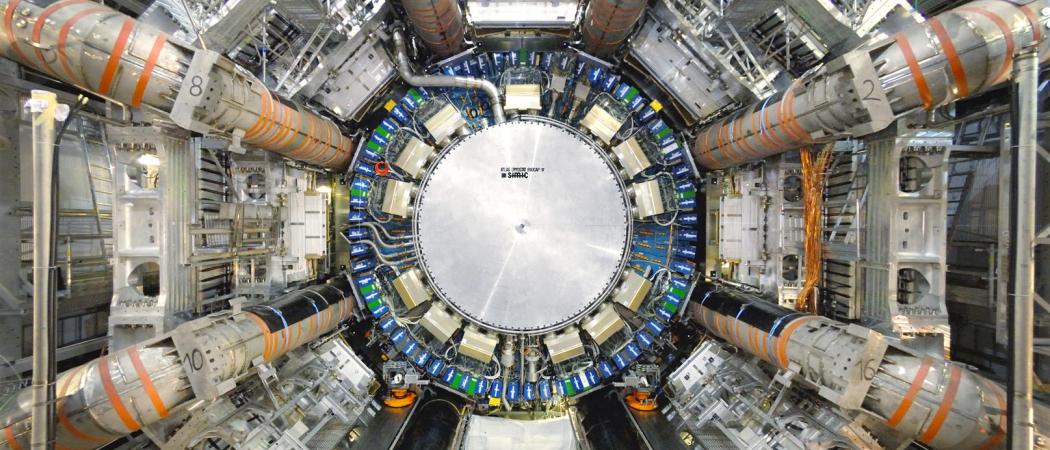

The ATLAS experiment at CERN, the world's largest research infrastructure

Research infrastructures each need coordinated funding plans in order to guarantee their long-term sustainability and enable them to deliver the expected economic impact, according to stakeholders meeting last month to assess the state of play and future prospects for 962 EU-backed projects spread across Europe.

“European science needs a coherent and sustainable research infrastructure ecosystem to take excellence to the next level and to deliver for society,” Jean-David Malo, director for open science at the European Commission told delegates at ‘Research Infrastructures beyond 2020 – sustainable and effective ecosystem for science and society,’ in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Under the EU’s next Framework programme for research and innovation from 2021 - 2027, the Commission hopes to improve on the current complex funding model, in which infrastructure projects are usually funded with a mix of national and EU sources, including cohesion funds and the Framework research programmes.

Under Framework Programme 7, the EU spent €1.7 billion on research infrastructures and has invested €2.4 billion to date under Horizon 2020. This was complemented by a further €18.2 billion from regional development funds.

As negotiations over the size of the 2021 - 2027 EU budget gather pace, stakeholders in the 962 infrastructures are worried about long-term sustainability. Even after construction is finished infrastructures need money to pay their staff and utility bills, to build new equipment and to finance research activities.

To ensure sustainability of research infrastructures, the EU, together with member states, wants to “establish an adequate framework for effective governance, long term funding, and maximum impact,” said Malo.

But the biggest obstacle is making sure everyone is committed to this plan and to agree on how to deliver it. At the current level of financing, the issue sounds like luxury problem, but even with enough money in the system, reorganising financial flow requires effort, new skills and changed mindsets.

Making better use of structural funds

In an ideal world, research infrastructures would have seamless access to both public and private funding at national, regional, and EU levels. But “different funding streams are coming through different rules,” said Jan Hrusak, member of Czech Republic’s council for large research infrastructures. Research infrastructures need to invest in both capital and human resources to keep up with the different regulations that govern funding sources.

“Synergies are hindered by different rules of national and EU programmes,” said Juan Maria Vazquez, secretary general for science and innovation in the Spanish government.

To solve this, the European commission would have to simplify some of its “overlapping” financial instruments, said Ilyiana Tsanova, deputy managing director of the European Strategic Investments Fund.

Also, not all funding sources can be used at different stages in the life cycles of research infrastructures. Structural funds are best suited for the initial phases and construction of facilities, while operational costs should be covered from national budgets.

Unfortunately, “the planning of infrastructures is not the first priority of a lot of science ministers,” said Milena Žic Fuchs, a member of the high-level group on maximising the impact of EU research and innovation programmes, known as the Lamy Group.

Better synergies between funding streams would enable research infrastructures to use structural funds in a more planned way, but practice does not always match policies devised in Brussels and European capitals. “We need to stop talking at the political level. We need to work at the governance level,” said Lukás Levák, director for research and development in the Czech Republic’s government.

Measuring performance

In addition to securing funding, infrastructures must tick off a few preconditions necessary for achieving long-term sustainability. Ensuring scientific excellence is paramount, but attracting and training managers and measuring economic impact is also very important for boosting the innovation potential of a research infrastructure, according to Fuchs.

But not all infrastructures meet these preconditions. A full 53 per cent of European research infrastructures do not apply international peer review for the selection of the user projects and for access, while 21 per cent do not have in place any kind of international advisory board to offer advice on the science agenda and portfolio.

Also, many research infrastructures do not have very clear key performance indicators and so it is difficult to evaluate goals and decide how to fund them. Research infrastructures should be able to know “what should be achieved with different sources of funding,” said Mateusz Gaczynski, deputy director at the Department of Innovation and Development in the Polish government.

Searching for customers

One way to set clearer goals and develop measurable performance indicators would be to set up services that can be sold to interested customers. Infrastructures should shift “from science driven to service driven,” said Erik Steinfelder, director general of the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI).

Research infrastructures could identify potential customers and provide services tailored to their needs. The research facilities could then be used by a broader audience, particularly private companies, NGOs and other organisations. To achieve that managers would need to “spread the word to the wider community,” said Steinfelder.

Such a setup would also help boost the innovation potential of research infrastructures, said Iain Mattaj, director general of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The knowledge coming from such facilities is generating industrial know how and economic growth. “A lot of technologies today come from developments in fundamental research, carried out at these infrastructures,” Mattaj said.

Research infrastructures and policy makers should agree on a way to connect the science with the needs of the society, said Marcus Nordberg, head of resources development at CERN. “I think it can be done, [research infrastructures] should play a key role.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.