The EU is offering new deals for countries to join its big R&D programme. Here's a rundown on the negotiating positions starting to emerge

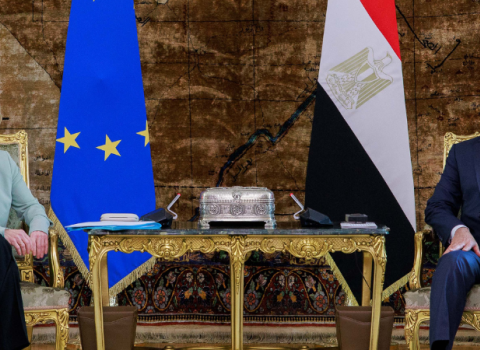

Anita Krohn Traaseth, CEO of Innovation Norway and Jean-Eric Paquet, Director-General, DG Research and Innovation, European Commission. Photo: Lysiane Pons, Science|Business

Quebec wants everything. So does Switzerland and Israel. Everybody loves Japan, but nobody’s sure they want China or the US involved.

That’s a quick check-list of negotiating positions now starting to be formed as a range of countries start considering whether and how to join the European Union’s next big R&D programme, the €94.1 billion Horizon Europe initiative. As it proposed the programme last June, the European Commission said it’s willing to offer new and improved entry terms, to make the programme an even-bigger platform for international collaboration than it already is.

Formal talks have yet to begin – and in fact, the only official move so far has been a November lunch between EU Research Commissioner Carlos Moedas and eight ambassadors. But from 2021, Horizon Europe opens up the possibility for more countries beyond Europe to gain associate membership, a legal status that allows countries to participate in EU research under the same preferential conditions as member states.

“Our goal for association is very ambitious and aimed at making it much more agile and palatable for a broader range of partners,” Jean-Eric Paquet, the Commission’s director-general for research and innovation, told a Science|Business conference in Brussels this week.

The message is appealing for a host of countries who say they want a deeper research relationship with Europe. But first, they want eyes on the terms and conditions. The basic deal is simple: if you pay into a common funding pot, your researchers can compete for grants alongside EU researchers. But there are a host of details yet to be discussed, or even described, by the Commission.

A problem is that many EU member states themselves have yet to clarify their own long-term, national research plans, much less imagine new deals internationally. And Brexit will delay any serious discussion, says Pierre Ouzoulias, a French archaeologist and senator, and vice president of the French Senate committee on culture, education and communications.

“I think it’s important to add ‘third countries’,” to Horizon Europe, Ouzoulias said, but, “nobody wants to add complexity” to the Brexit talks by doing deals with other countries for Horizon Europe. It will be some months before negotiations with anybody can get serious, he thinks.

In the meantime, Science|Business has spoken to officials and researchers from several non-EU countries, familiar with their government’s wishes on research.

Nothing is decided, but to help aficionados of the process, or even those with a passing interest, here’s a guide to the signals several big countries are sending out.

Canada

With Canada, it’s a bit complicated. Its French-speaking province, Québec, definitely wants full membership in Horizon Europe – but the federal government has yet to take any formal view for the country as a whole, and is unlikely to do so before this Autumn’s national elections. There are also competing priorities, such as seeking research partnerships with China, and, if not with Trump’s Washington, then at least with individual US states such as California and Massachusetts.

But Québec is clear: “I want us to be an associate member,” said Rémi Quirion, chief scientist of Québec.

The flexible entry terms Paquet talks about are the main selling point. “For Horizon 2020 we had the opportunity of participating; it was not straightforward, it was a chore,” said Philippe Tanguy, CEO at Polytechnique Montreal.

But there’s also the not-insignificant matter of the man at the helm in the US right now. Canadians frequently mention President Donald Trump and his policies as a motivator for embracing Europe more tightly. “The geopolitics have changed. It’s a little harder to collaborate with our southern neighbours,” said Tanguy. “We have excellent ecosystems [in Canada] and you have them (in Europe). There’s plenty to share.”

“What’s happening in the US with the current president is an opportunity for us. We need new friends,” Quirion agreed.

China

In its rush to global scientific prominence, China now produces more academic articles than any other nation except the US, and has more laboratory scientists than any other country, and outspends the entire EU on research and development. And yet, “China does not appear to be an obvious candidate” for association, Paquet said. European officials are wary about Chinese intentions in the world, and recent years has seen frequent sparring over cheap Chinese-made solar panels and intellectual property.

The country is not known to have expressed an interest in association status to Horizon Europe, but it would fall short of meeting the required entry criteria anyway, Paquet suggested. According to the Horizon Europe proposal, associated countries must demonstrate “fair and equitable dealing with intellectual property rights, backed by democratic institutions”.

However, Paquet expects the Chinese will still be involved in parts of the new programme, so long as they bring their own funding. “The tables are turning with China – it is becoming a scientific powerhouse. Whether the broader political framework goes along with it is a big discussion,” he said.

Israel

Israel is currently participating in Horizon 2020, and is keen on having full access to Horizon Europe. But the EU is playing it cool. The Horizon Europe legal text, published last summer, puts the country in a category of wealthy countries that may be barred from a particular raft of innovation-focused programmes, such as the European Innovation Council (EIC). With a proposed €10 billion to spend, the new funder aims to help founders do what’s seemingly impossible: scale-up in Europe.

According to the legal text of the programme, “with the exception of EEA (European Economic Area) members, acceding countries, candidate countries and potential candidates, parts of the programme may be excluded from an association agreement for a specific country.” The text proposes to give the EU a right to exclude countries from specific parts of the programme if their involvement would risk undermining the core goal of “driving economic growth in the Union through innovation”. The new conditions are also designed to prevent third countries making financial gains from Horizon Europe, or putting in more money than they take out.

The text carries the same threat of partial access to Switzerland (See below).

EU negotiators appear ready to drive a hard bargain with Israel, a country that excels in winning European Research Council grants. Tel Aviv will feel it has some good arguments to bring to the negotiating table. There’s the history: the country was the first non-European country to formally associate to the EU Framework Programme back in 1996. Israel also has a roaring venture capital scene, and if the EIC really is intended as a better bridge to the financial world, there will be a compelling argument to involve the country in the competition.

Japan

Japanese researchers are suddenly in high favour in several EU capitals – and while there have yet to be any formal pronouncements, Brussels handicappers suggest that it and Canada are probably first in line among the new entrants to Horizon Europe association. Though the country’s research establishment has long been relatively inward-looking, lately that position has been changing. A small example: the country’s top researcher, Riken Institute, has just opened a Brussels office. The EU and Japan just inaugurated a sweeping new trade agreement. And officials in several EU member states have been talking up a Japanese partnership.

“I love Japan,” said Matthias Kleiner, President of the Leibniz Association. “I think it would fit in an excellent way as a partner in European research.”

Norway

Norway’s full access to Horizon Europe is secured by dint of its membership of the European Economic Area, which puts it inside the single market. Thanks to Brexit, “The awareness of the value of this agreement has never been clearer. It gives countries like us an awakening of how important international cooperation is. It puts the EU in pole position,” said Anita Krohn Traaseth, CEO of Innovation Norway. For her country, there are some obvious areas of cooperation: maritime and shipping, climate and energy. Of particular interest for the Nordic country is the EIC. “We applaud the idea. It’s really important, because you’re building a bridge to industry but also VCs and SMEs.”

With the ERC, the EIC could “re-phrase the whole brand of EU, making it an attractive place to do innovation,” Traaseth said.

South Africa

South Africa is considering the possibility of associating to Horizon Europe among various options for cooperating with EU research – but it already has such an active role in the EU’s research programmes that it isn’t clear it actually needs that new formal status. As the biggest science player in Africa, the country has long participated in individual EU projects, with the EU paying the bill. Under Horizon 2020, South African researchers participate in more than 130 different projects. They include efforts to develop new medicines and vaccines for malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS, to improve satellite earth-observation systems, and to study the south Atlantic Ocean. The EU also co-funded the planning for the country’s biggest science project, the Square Kilometre Array. When it opens, it will be the world’s biggest largest telescope, spread across southern Africa and Australia.

As for the country’s future role in Horizon, “we’re looking at all the options on the table,” said Daan du Toit, deputy director-general at South Africa’s Department of Science and Technology. “We have been very successful in the Framework Programme; Europe is a valued and strategic partner. We need to understand what association means” before making any decisions on whether to seek that status. Last November, South Africa was among eight countries whose ambassadors attended a lunch with Moedas – but beyond that, no serious discussions have yet begun.

Switzerland

A possibility that Switzerland could be locked out of the innovation sections of Horizon Europe is hugely disappointing for Swiss scientists. The problem is that the country’s bid to gain full access to the programme is tangled up in a wider political fight. Until now, associate status granted a country full access to the EU research framework.

Though never an EU member, Switzerland has access to EU markets and programmes via a web of more than 120 bilateral deals and has participated in EU research programmes since 1988.

Privately, the Commission says there’s a strong case for the country to retain full access to the programme. Switzerland argues that it has a lot to offer European science. “My lab is collaborating with 500 different institutions in Europe,” said Alessandro Curioni, director of the IBM Research Lab in Zurich. “I do hope we will arrive to a situation where this value is understood and it will allow us to participate in [Horizon Europe] in the same way [as before].”

The UK

A whole host of Brexit factors could make the UK’s path to full membership complicated. The country is calling for the closest possible science relationship with the EU after Brexit. It also wants a formal say on areas of EU science direction in which it has agreed to participate. While it seems unlikely to be given this privilege, the scale of the UK’s research strength is such that many feel it would inevitably have a large say – at least informally – about the direction of the programme.

There is broad support among Europeans for UK association to Horizon Europe. But the terms of entry, some politicians say, should be strict. “They should be part of all or none. No cherry picking,” said Stefan Kaufmann, Bundestag member and chair of the CDU/CSU group on education and science, told Science|Business last month. “They have to pay [to join], like Israel or other associated states.”

For now, key information on Britain’s future – as everything about Brexit - is yet to come.

The US

US researchers are already among the most frequent developed-country participants in Horizon projects – but only rarely with EU money; usually, their involvement is funded by US agencies. A special “implementing arrangement” to facilitate this was agreed between Washington and Brussels. But generally, American science agencies prefer to work directly with science agencies in the individual member states, such as Britain, Germany and France. US officials say they find it simpler to collaborate that way, rather than negotiate the complex legal and administrative procedures of the Commission.

In 2017, the US State Department submitted a memorandum to the EU suggesting several changes it would like to see in Horizon Europe – mostly in the area of making it easier for Americans to sign EU contracts without running afoul of US funding rules. And the then-acting US mission chief in Brussels joined the Moedas meeting last November with ambassadors exploring association with Horizon. Still, officials in Washington say the US is unlikely to take up such an offer – which is just as well, as politicians in Germany, France and other member-states have already said they don’t want the world’s dominant science power getting more deeply involved in Horizon than it already is.

“The supremacy of the Anglo Saxon world in science is a difficult thing” for Horizon to manage, says France’s Ouzoulias. “The principle of having international cooperation is good, but we can be pragmatic: Cooperation, but with diversity”.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.