Researchers in the UK were overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit. Now, new estimates of lost funding show these concerns were justified

Anne Glover, Vice Principal for External Affairs and Dean for Europe. Photo: The Royal Society of Edinburgh

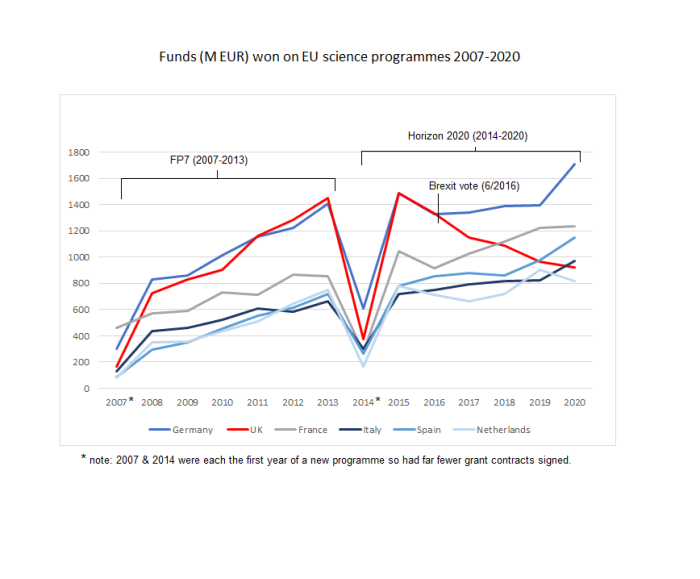

On the fifth anniversary of the vote to leave the EU, a new analysis by the Scientists for EU campaign shows that following the referendum in 2016, the value of grants the UK won in the EU Horizon 2020 science programme steadily plummeted up to the end of the programme last December.

Before the vote on June 23rd 2016, the UK was consistently neck-and-neck with Germany over many years on both participation counts and total grant amounts. If the UK had not voted for Brexit and kept pace with Germany, it would have won some £1.46 billion more in grants than was the case, according to Scientists for EU.

Between 2017 - 2020, the UK dropped from a longstanding joint first place, to fifth place. By 2020, the UK won less money and participated in fewer projects than Germany, France, Spain and Italy, and was only just ahead of the Netherlands.

Without Brexit, it is estimated the UK would have participated in 2,742 more projects, or about 30% than it actually did, from 2017-2020. Reasons for disruption include the constant threat of a possible no-deal situation, given there was no agreement on the terms under which the UK would leave the EU until late in 2019, coupled with uncertainty over the UK’s long-term future in EU research programmes. This made the UK a higher risk partner in consortia, and it was also higher risk for UK institutions to put in applications, not knowing what the long-term future held.

Building back

Horizon 2020 has now handed out all its grants and the new €95 billion Horizon Europe is starting up. That raises the question of if and how the UK can build back its position, or if too much momentum been lost.

The European Commission has put the UK on a list of 18 would-be associate countries it says can start applying for grants pro tem, while final formal agreements are put in place. UKRI, the main UK public funding agency is encouraging academic and researchers to start applying for Horizon Europe grants.

But, says Scientists for EU, “Is the agreement certain and stable enough that UK institutions feel confident enough to compete?” and “Do EU and other associated countries feel as confident as they were pre Brexit to take on a UK partner?”

“Looking ahead, UK science will want to regain quickly its leading role on the European science programme. Brexit uncertainty over five years has knocked the UK’s position down several rungs and blown a huge hole in our funds and networks,” said Mike Galsworthy, director of Scientists for EU. “We do need a plan to build back better in Europe after Brexit, and this is not something the government can ignore.”

Anne Glover, president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, former EU chief science adviser and a supporter of Scientists for EU, agreed the damage from five years of Brexit uncertainty and antagonism has been immense for UK researchers, who were so used to being able to collaborate with colleagues all over the continent. “To stop the decline we must engage in positive initiatives fast,” she said.

The Royal Society of Edinburgh recently launched the Saltire research awards in collaboration with the Scottish Funding Council and the Scottish government, in a bid to reinvigorate Scotland’s research partnerships with Europe following the double blow of Brexit and COVID-19.

“That initiative is the kind of bounce-back and re-engagement we need. Not just in Scotland, but everywhere,” said Glover. “[Prime minister] Boris Johnson talks of the UK being a “science superpower” but this will only be achieved by an appreciation that he has a huge amount of recent vandalism to undo on the way back to any such international position,” she said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.