New report calls for ‘Choose Europe’ programme as way to tackle precarity in research careers

Manuel Heitor, chair of the European Commission’s expert group on the future of the Framework Programme for research and innovation. Photo credits: CESAER

The CESAER university association is calling on the European Commission to pilot a ‘Choose Europe for a research career’ programme to tackle brain drain and precarity in research careers.

CESAER’s new report, which contains an analysis and case studies on researcher employment in European universities, suggests the Commission should pilot the programme in 2025.

“The Commission must lead the charge in reversing brain drain out of Europe by implementing a ‘Choose Europe for a research career’ programme and enforcing the free circulation of researchers and scientific knowledge across Europe,” the report says.

The pilot would offer extensions of two to three years to postdoctoral fellowships funded by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) COFUND projects, with the caveat that the host institutions commit to longer-term job opportunities.

MSCA’s COFUND programme already promotes best practice for research careers by enforcing high standards in working conditions as it co-funds researcher training and mobility. The pilot action would extend the fellowships to four to six years.

Manuel Heitor, CESAER’s research careers envoy and co-author of the report, presented the idea in a recent conference held by the European Commission. A recommendation to create ‘Choose Europe’ also features in the influential report on the next EU Framework Programme, FP10, drafted by an expert group led by Heitor.

Heitor says there is plenty of support for the pilot as well as money in the EU budget. The Commission simply needs to trial it.

“The goal is just to enlarge and make minor changes in the existing scheme and prepare it so that in the next framework programme we can have a large programme,” says Heitor.

This is not a new battle. Heitor, alongside other activists, has been trying to convince the Commission to take the lead on tackling the precarity researchers face in employment for years.

In 2021, he led work on a joint member state agreement to do more when he was science minister for Portugal, which then held the EU Council presidency.

Now, with this latest report, Heitor wants all the stakeholders – the Commission, national funding agencies, and public and private institutions – to take responsibility and commit to real change. “Our case is clear in the need to combine new co-funding schemes with co-responsibility to make this happen,” says Heitor.

Universities lay it bare

The 24 universities CESAER members that contributed to the report are ready to do their bit. “Our analysis showed that universities are ready, but there is a need for responsible recruitment practices,” says Heitor.

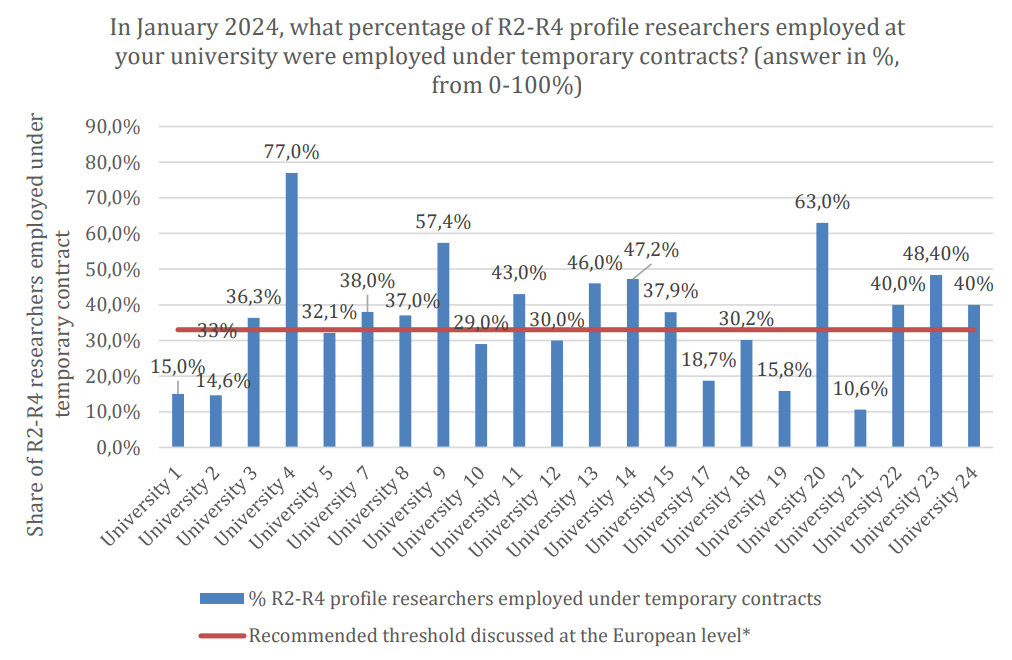

The association surveyed its member to find out what the trends in employment are and found an extremely diverse picture. The proportion of researchers on temporary contracts, for example, varied from 10.6% to 77% in its member universities. EU recommendations suggest this number should not exceed one-third.

The contract duration varied widely too, but the majority were short-term, with up to one year and two-to-four-year contracts dominating in most institutions. The collected data only considered researchers who hold a PhD, or equivalent.

The universities reported that reliance of short-term project funding contributed to the overreliance on temporary contracts. Others pointed to legislative frameworks as contributing factors too. In most countries, researchers are subject to the same rules and regulations as other workers, which are not designed with the research workforce in mind.

At the same time, three quarters of universities indicated that they consider their mix of temporary and non-temporary contracts ‘about right.’

Some are outliers. The University of Bergen, presented as a case study in the report, employs more researchers at higher categories of expertise with permanent contracts than lower category temporary workers. It’s the opposite of a usual European university.

The university has managed to achieve this balance thanks to a long-term collaboration with the Trond Mohn Research Foundation, which enables early career researchers to lead four-year research projects. This allows them to grow professionally and thus qualify for permanent positions within the university.

Collecting data and finding balance

CESAER suggests the survey could serve as a blueprint for the Research and Innovation Careers Observatory (ReICO), which the Commission runs with the OECD.

The observatory, although welcome, has been criticised for its limited data collection capacity, mostly collecting national data which does not contain detailed enough information. Institutional data is needed to make the observatory work, stakeholders believe.

“Any observatory will need to require institutional data, this is very clear,” says Heitor. “This is a way to provide new ideas for the OECD on how to do it.”

In the end, while an EU-wide push is needed to gain momentum, and national commitment is necessary, each institution employing researchers will have to put in the work to give researchers fair working conditions.

This is partly because universities must retain their independence in managing this issue. “We should not interfere in the recruitment decisions of universities, because this is an issue of autonomy,” says Heitor. He believes the keyword is co-responsibility.

Money is the other part of the puzzle. Tackling precarity means making space for more permanent contracts. These cost money, and universities often rely on a large chunk of unpredictable project funding in their own budgets. But there are ways to leverage money. If the University of Bergen can develop a scheme that works, Heitor believes, “there is no reason why they could not work elsewhere.”

You can read CESAER’s full report, including its extensive recommendations for the different stakeholders, here.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.