Some rectors of the country’s civilian state universities have secured third or even fourth mandates, a trend that is of concern to the European Parliament and others in the higher education sector

The University of Bucharest in University Square, Bucharest, Romania. Photo credits: John R Chandler / Flickr

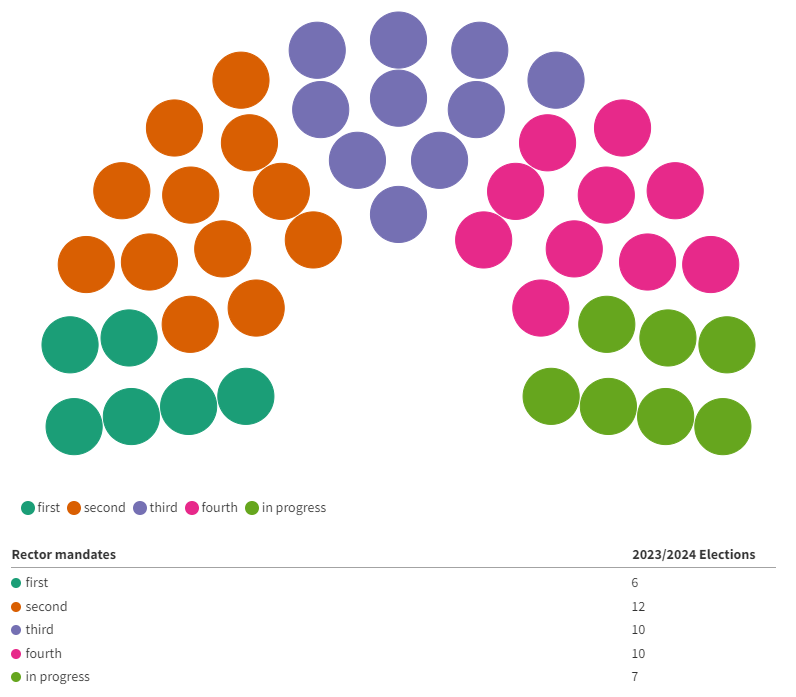

Recent elections of rectors in Romania have extended long-standing leadership in universities across the country, with only six of 38 civilian state universities voting in new rectors. The rest saw their incumbent leaders secure additional terms – more than a quarter for the fourth time.

This trend, highlighted by a European Parliament report and some leaders of higher education institutions - enabled by a legislative loophole - is raising concerns about the future of innovation, research, and governance within Romanian universities.

The letter of the law allows rectors to serve two terms, but slight changes in wording of the legislation opened the way for rectors to take short breaks from their job and then re-run for a third mandate.

In 2023, Romania adopted a new higher education law, which established another clear limit, but it also reset rector’s mandate counts to zero and extended the term from four to five years. Without breaking the law, rectors who secured a seat in 2012 and made full use of the loopholes could theoretically extend their leadership until 2034.

As a result, more than half of winners of the recent elections in Romanian universities are on their third or fourth mandate. Another 30% of university leaders secured their second mandate. Of the six newly elected rectors, only three of won against the incumbent. In half of the situations, it was the decision of the former rectors to not run. Some of the incumbents ran without competition, but in the majority of cases there was at least one alternative.

To be a challenger is particularly tough. “The incumbent rector is able to build a solid network of supporters, those who had direct access to resources, projects/grants, etc,” said lecturer George Țăranu, who was the one of the lone election outsiders. Țăranu ran and lost against the incumbent rector of the Gheorghe Asachi Technical University of Iași, who managed to secure a third mandate this February.

Slippery slope

The power grab in higher education sets Romania apart from other European universities. The European Parliament highlighted the issue in the “EP Academic Freedom Monitor 2023” released this February. The report criticises not just the mandate reset, but also the fact that the new higher education law allows rectors to serve for an additional five years after retirement age, based on an annual review.

Leaders of the University of Bucharest have repeatedly warned that loopholes introduced into the higher education law from 2014 onwards would allow this to happen. Legal expert associate professor Claudiu-Paul Buglea, who is president of the University’s Senate, says it was immediately clear where the loopholes would lead. “I discussed this wherever I could with those from the Ministry of Education. I was 100% convinced that this would happen.”

The consequences of these long-term leaderships are significant, Țăranu warns. "One of the main losses is the capacity for innovation.” An unchanged leadership can become rigid, clinging to outdated strategies, setting back the institution, while markets, technologies and society evolve rapidly. Prolonged leadership can also stifle idea diversity, creativity, and staff motivation within universities, Țăranu points out.

At the same time, the legitimacy of the electoral process is at stake. "The main thing that needs to be protected by a limit on rector’s mandates is university democracy”, says Buglea. While rectors who are running for a third or fourth term do organise elections, maintaining a figleaf of democracy, the odds are extremely skewed in their favour. “If they did not make a flagrant mistake, they will win the next term nine times out of ten,” Buglea said.

Incumbent rectors defend their long tenures, citing the need for continuity and consistency. Vasile Abrudan, re-elected for a fourth term as rector and president of Transylvania University in Brașov, argues that an advantage of uninterrupted long leadership is the "continuity in applying a coherent strategy for the development of the university, which is extremely important in a society with a frequently modified legislative framework.”

Abrudan underlines the fact that in the past 12 years there were 14 different ministers of education and that public authorities are affected by frequent changes in political or strategic orientations and leaders.

Universities are taking action

Some universities have taken matters into their own hands. The new charter voted by the academic community of the University Babeș-Bolyai of Cluj in 2024 puts down a limit of two mandates. The University of Bucharest also recently restated this limit, which was originally introduced in university’s regulations in 2016, at the proposal of the sitting rector of the university. “The fact that the idea came right from the incumbent rector was very important. At that time, there was no discussion and no dilemma about this in the senate”, said Buglea who in 2016 was a member of the senate.

Buglea became keenly aware of the advantages a former rector could have in a university electoral competition, as he went head-to-head with the former rector for the position of the president of senate in 2019. He says that many were sceptical of his chances, but he wanted to offer the community the chance to have an alternative. Buglea did win those elections and then once more, in four years, which reinforced his belief in the need for democracy in universities.

Last year, Buglea oversaw the revision of the university’s charter, where the two mandate limit was kept. "As a fact we are now trying to readapt, to modify the charter again and we might reduce the terms, to a maximum of two terms for deans as well,” he said.

Other universities, though, are moving in the opposite direction. The University of Craiova, which had an existing limitation of two rector mandates through its charter, removed this limit in a recent revision. Elections results are now highly disputed because they were organised before the revised charter came into force and helped secure a third mandate for the rector Cezar Spînu.

Two other elections were so marred with irregularities that the Ministry of Education decided to overturn the results. The University of Arad had elected Ramona Lile for the fourth time even though she had been banned from running for a leadership position due to a previous decision by the National Council of Ethics, which found plagiarism in her work.

Similarly, at the University of Galați, Puiu Lucian Georgescu's election was not confirmed by the ministry due to irregularities found in a govarnment report, and his attempt to block the minister's order was rejected by the local court of Appeal.

The impact of these legislative changes on Romanian higher education cannot be overstated, Țăranu warns. "I believe that the amendment of the higher education law favouring incumbent rectors will represent a major setback for those universities where the same rectors were re-elected, practically remaining for almost 20 years. The impact on society will be extremely important and we will see the results in the next 10 years."

Science|Business contacted the Ministry of Education for comment but did not receive any response.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.