With prospects of association to Horizon Europe receding, the UK now finds itself excluded from quantum projects to which it previously had access. UK companies awarded grants can’t take part and projects may be scrapped if UK participants cannot be replaced

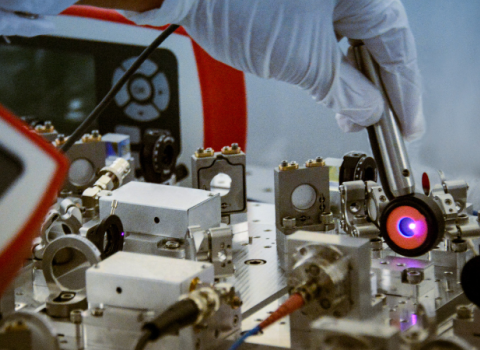

The possibilities of quantum technologies have set off a global race for development Photo: IBM Research / Flickr

The EU moved to exclude the UK from Horizon Europe calls on sensitive quantum projects in October due to doubts over the country’s willingness to provide EU researchers with reciprocal access to UK programmes and to comply with intellectual property rules.

The move reverses the EU's previous decision to accept UK participation in more mature quantum projects with high ‘technology readiness levels’.

In spring 2021, the UK, Switzerland and Israel were excluded from calls relating to quantum sensors, simulators and telecommunications, with the EU citing security reasons.

But following objections by member states and researchers, at the end of 2021 the European Commission decided to open up 2021 - 2022 calls to certain UK entities if they gave reassurance they would protect EU strategic interests, assets, autonomy and security, and respected reciprocity and intellectual property conditions.

Now, after assessing the proposals submitted by the UK, the EU has excluded quantum technologies companies that applied to take part.

"Despite earlier statements from the UK side, when the moment of verification came, the EU realised that these reciprocity conditions were not on the table, and we got to the point where the Commission was not seeing enough evidence for an inclusion," said Tommaso Calarco, director of the Institute for Quantum Control in Jülich, and one of the coordinators of the Quantum Flagship, a multi-billion EU Commission research initiative.

Reciprocity was not the only issue, as there were also concerns about intellectual property. When countries cooperate, "Ideas and background around the projects are shared. Unfortunately, the risk that a UK entity participating in a project, and therefore having access to all information, might spin-off a start-up which could eventually end up being acquired by extra-European countries, could not be excluded," Calarco said.

In substance, said Calarco, some conditions for cooperation between the parties weren't sufficiently fulfilled, and this was reflected in the quantum technologies field, since the sector is widely considered a potential strategic asset.

"I hope all these issues will be solved, as these partners – including the Swiss – have important roles and competencies in quantum projects and we are forced to find somehow substitutes or alternatives to develop quantum technologies, and this is not easy," he said.

The move has been met with disappointment and discontent by UK officials and the industry.

"We are surprised and disappointed in the EU's last-minute decision to exclude the UK from quantum research projects. It sends a poor signal at a time when the UK is seeking to finalise our association to Horizon Europe, despite the EU's refusal to implement the agreement reached in 2020," a spokesperson from the UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy said.

For UK entities directly involved in the projects, the exclusion is causing terrible headaches.

The disappointment is particularly strong for UK companies that were part of consortia and had been successful in being awarded funding, and which have now found out they will be unable to participate.

Cooperation will continue

However, Nathan Johnson of the Silicon Quantum Devices group at University College London’s Centre for Nanotechnology, says the effect of exclusion could be limited. "The UK government is a quite well-funding the quantum industry,” he said. “There is also a relatively strong private sector funding start-ups and venture capital. In addition, [. . .] there is a lot of collaboration among people in quantum anyways."

A similar view is shared by Maksym Sich, CEO and co-founder of quantum photonics start-up Aegiq, a 2019 spin-off from Sheffield University. Arrangements between the UK and the EU are not a closed-door policy but allow for some degree of cooperation. The UK government will somehow make "arrangements to create a functioning quantum ecosystem within the west,” including the EU, he said.

In any case, Sich said, "There has always been a bit of a special distance between the UK and the EU" back in pre-Brexit days.

The UK is due to publish a ten year quantum strategy, and in the meantime, is setting up partnerships and cooperation agreements with the US, and more recently, Switzerland.

The political row over the Northern Ireland Protocol, which has held back UK association to Horizon Europe, despite it being agreed as part of the Brexit withdrawal agreement, has undermined trust. This is now being reflected in the quantum technologies field, as the sector is widely considered a potential strategic asset.

The Quantum race

Quantum technologies aim to take advantage of quantum physics properties to reach performance levels that are otherwise unattainable and, given their dual-use nature, are set to have unprecedented impacts in the civil and military domains.

This has triggered a quantum race worldwide, with European countries including the UK, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy and Spain setting up national research programmes. At the EU level, besides the Quantum flagship, the Commission has launched a series of initiatives through Horizon Europe, Digital Europe and programmes.

In common with other European countries, the UK sector is composed mainly of start-ups and spin-outs from academic research. It is a leader in Europe according to the 2022 Quantum Technology Monitor published by the consultants McKinsey, which says the US has the largest market at $2.164 billion in 2021, followed by the UK with $979 million, Canada $658 million, and the EU $294 million.

Without a rapprochement between the EU and the UK, quantum consortia will need to modify their proposals and find other partners or coordinators to replace UK participants. Should the remaining partners not be able to change the proposal on time, the grant agreement would not be signed, and the project would not take place, EU sources said.

Israel has provided the required guarantees and has been admitted to high level EU Horizon quantum projects from the end of last year, apart from ones involving space research. However, Calarco said few Israeli groups are involved.

Switzerland, however remains excluded, a ban that is seen in the country as counterproductive and damaging, favouring competitors.

"All the parties, Switzerland, the UK, and the EU, are shooting themselves in the feet because [the loss of cooperation] will cause a big disruption, and companies in the US and Asia will eventually profit from the situation," said Grégoire Ribordy, CEO of the Swiss quantum sensing company ID Quantique. “We would be better working together in Europe rather than fighting internally having a disruption,” he said.

Ribordy set up another entity in Vienna to sidestep the Horizon Europe exclusion. However, it is not clear of this will work because the ban relates not only to location, but also to ownership.

Maryline Maillard, head of EU and International Affairs at ETH Board (the supervisory body of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology), said disrupting collaboration among Europeans has a very negative outcome. "The competition is not in Europe nowadays; it's clearly with the rest of the world such as the US and Asia," she said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.