US tech could be used for “regime change” in Europe and make businesses vulnerable to a Washington-operated “kill switch”, they worry

Photo credits: Anirudh / Unsplash

MEPs are urging the EU to finally build technological independence from the US after transatlantic relations nosedived over the past six weeks.

For decades, the bloc has nibbled around the edges of US technology power, launching investigations and issuing fines to its biggest companies. But despite years of talk in Brussels about “strategic autonomy,” Europe has remained largely dependent on American digital services.

But now, with US security guarantees in doubt, Washington voting alongside Russia in a United Nations resolution on Ukraine, and US president Donald Trump berating Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the White House, some MEPs argue that US dependence has become an acute risk to European democracy and business.

“It's the right time to pick up the tech confrontation,” said Alexandra Geese, a German Green MEP focused on digital services. “Because what the US administration right now wants in Europe is regime change. They want the authoritarian parties, the far right, to take power.”

Geese has pointed to research suggesting that, during the recent German federal election campaign, the social media platform X gave far more prominence to posts from Alternative for Germany (AfD), a far-right party supported by X’s owner Elon Musk. This boost could not be explained just by AfD posts having more engagement, the study found.

“Tech is the instrument they have to bring about regime change in Europe,” argued Geese. She wants a full European Commission investigation of major social media platforms to understand why misinformation spreads more than information, and the replacement of algorithms that have this effect.

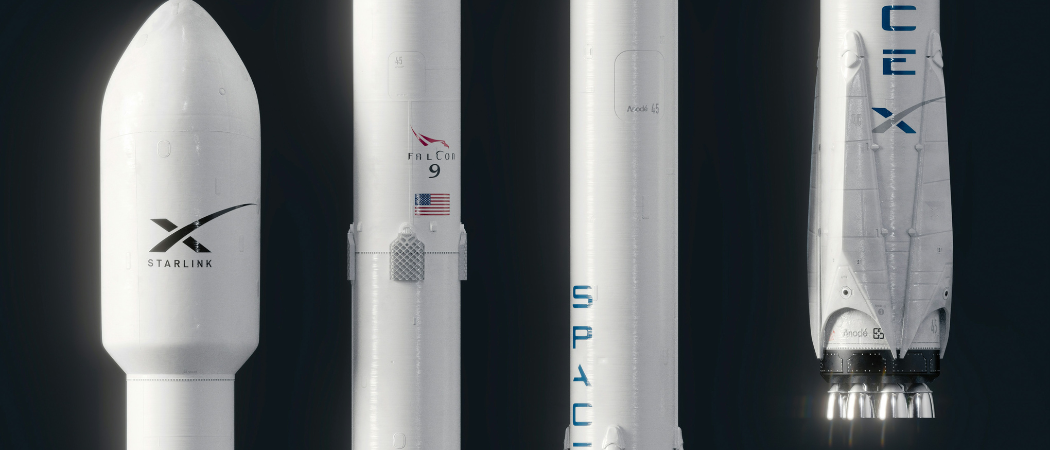

Right now, however, the most pressing issue for Europe is building up an independent military and satellite system, creating an alternative to Elon Musk’s Starlink. Three European companies, Leonardo, Airbus and Thales, have discussed a satellite alliance, for example.

Earlier this week, Musk and Polish foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski clashed online over Ukrainian access to Starlink. “If SpaceX proves to be an unreliable provider we will be forced to look for other suppliers,” Sikorski warned.

But attention is also turning to wider questions of digital sovereignty, such as cloud storage.

“The discussion on strategic autonomy in Europe has accelerated a lot due to the events of the last weeks,” said Brando Benifei, chair of the European Parliament’s committee on US relations. “In Europe we lack certain infrastructure, like platforms and cloud.”

“In the Parliament and Council I see strong support for more digital sovereignty and autonomy,” he added.

Still, the bloc is treading a delicate path, and there could be risks to launching a major confrontation with US tech firms while trying to salvage at least some US support for Ukraine.

“This is not about antagonising the US,” said Matthias Ecke, a German Social Democrat MEP, but rather making clear that access to the single market “comes with the obligation to respect its rules.”

Virtual kill switch

Europe has long bemoaned its dependence on US technology firms, but little has shifted. Amazon, Google and Microsoft still have a nearly 70% share of the European cloud computing market, while Europe’s biggest provider has just 2%, according to a report released last month on how the continent can build a more independent digital “EuroStack”.

Common projects, like Gaia-X, which attempted to build a European cloud, have failed to make a dent.

But with the US now seen as erratic and sometimes hostile to the EU, there are also concerns that dependence on US tech firms is not just an economic disadvantage, but a full-blown business risk.

Privately, European chief executives and policymakers are worried that the continent’s businesses are “no longer insurable” because they are based on American data, AI or other digital tools, potentially giving Washington a “virtual kill switch” over the European economy, said Martin Hullin, director of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s digitisation programme, one of the thinkers behind EuroStack.

“Whoever you speak to, it's an underlying fear,” he said. “If it's reasonable, that’s a whole other question. But clearly you have precedents.”

Serious risk

He pointed to the US aerospace firm Maxar, which earlier this month disabled Ukrainian customers’ access to satellite imagery after the US government temporarily halted intelligence sharing with Kyiv.

The US could use its technology leverage to snuff out a European civil society initiative it didn’t like, he warned.

This has happened before, at Beijing’s request: in 2020, Zoom shut down the accounts of US-based pro-democracy activists following demands from the Chinese government.

At a recent conference of European cloud service providers, executives expressed similar concerns over business continuity, said Geese. “There's a serious risk that that data is used by the US administration or that it can be shut down,” she said.

Of course, major US tech firms like Microsoft are unlikely to want to jeopardise their European markets by proving unreliable, Geese acknowledged. “But they might not have a choice,” she said. “They're under US jurisdiction.”

EuroStack

But it’s still unclear exactly how Europe extricates itself from US technology across so many sectors, and how much money this would cost.

The EuroStack report, written with the help of Geese and several other MEPs, maps out a more autonomous technology system ranging from the raw materials needed for batteries right up the software needed to run businesses.

It wants a European Sovereign Tech Fund to step in, initially providing €10 billion to support this transition. However, it estimates €300 billion would be needed over a decade to fully achieve its goals, although some of this would come from private investment.

Hullin stressed that Europe doesn’t need to follow the US “playbook” of building up its own tech giants with massive economies of scale.

“It doesn't need to be a choice between the hyperscalers in the US nor the Chinese kind of state derogation approach,” he argued.

Instead, Hullin thinks tie-ups between medium-sized European companies, using common digital standards, can compete with the US behemoths.

EuroStack is also keen on open-source solutions, rather than private ones. “We want a different digital universe, which is built around open standards, open source, fair business models, where everybody can chip in and jump in,” said Geese.

She wants public procurement rules to force European countries to buy cloud storage and other digital tools from domestic, not US, providers. “We have a great tech landscape in Europe. What we don't have is demand for it,” she said.

Benifei’s main priority is to complete the European Capital Markets Union, enabling finance to flow more freely across borders and European savings to flow to European, rather than American, companies. “This is the first step to digital sovereignty,” he said.

Digital non-aligned movement

Europe could also team up with other countries, such as Brazil and India, that also don’t want to be dependent on US or Chinese technology, argued Cecilia Rikap, head of research at the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose of the University College London, and one of the contributors to EuroStack.

Brazil is seen as one of the leaders in open source digital infrastructure, and the country has fined X and forced it to block accounts accused of spreading misinformation.

Last December, Rikap and several other European academics argued for what they call a “digital non-aligned movement,” which Europe could be a key part of. This movement would push for a “universal public option of open-access, non-profit digital services,” said their report, Reclaiming digital sovereignty. In recent months, Rikap has been presenting her research within the Commission and to MEPs.

The EU, of course, might be reluctant to build joint digital infrastructure with countries like Brazil or India, acknowledged Rikap. “But that’s not a problem,” she said. “It’s a matter of degrees of coordination.”

In late February, the Commission visited India, and promised “interoperability” of their digital public infrastructures, as part of a broader package of digital and research cooperation.

Far-right question

One political unknown is whether a push for European digital sovereignty would also be supported by the rising parties and governments of the far-right.

They may be ideologically aligned with the US under the Trump administration, and willing to cut deals that undermine wider EU unity. Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni struck a Starlink deal with Musk, although this has yet to be finalised and faces fierce opposition domestically.

But at the same time, far-right parties also typically stress national sovereignty. Independence from US power has been a long-held dream of French nationalists, for example.

Sarah Knafo, one of the last remaining MEPs of the French far-right Reconquête party and one of the few French politicians to attend Trump’s inauguration, is the rapporteur on a parliamentary report on European technological sovereignty and digital infrastructure that raises similar concerns to Geese and other left-of-centre MEPs.

Geese said the report was originally partly her idea, but Knafo’s parliamentary group, the Europe of Sovereign Nations, eventually gained the rapporteur position in the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy.

Knafo’s report echoes many of her points, for instance cloud dependence and the need for more domestic public procurement, although it does not mention social media. “The EU is dependent on foreign technologies, which means it faces significant risks,” it says.

But Geese and Benifei are sceptical that Europe’s far-right parties will actually support European digital sovereignty, and are ultimately likely to follow the lead of Trump and Musk.

Far-right parties “want Elon Musk promoting [them] on Twitter,” argued Geese. “They're going to fight for their own power. They know where their power comes from: it comes from social networks.”

Knafo did not respond to a request for comment.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.