Scales to assess the likelihood of a new technology being accepted by consumers are helping to make sure innovators think about how their inventions will be received

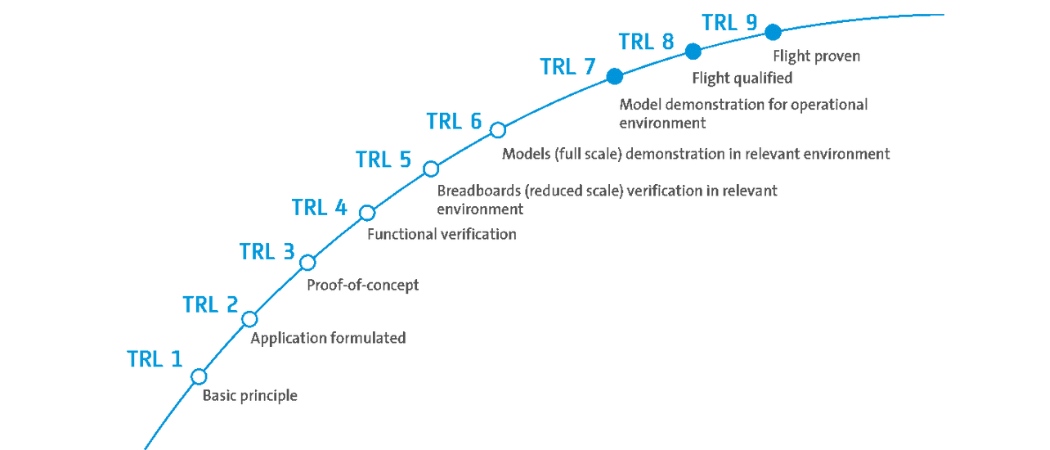

Technology Readiness Levels scale. Photo: European Space Agency

Technology readiness levels (TRLs) indicate how close a particular innovation might be to the market, but say nothing about the likelihood people will want the product and be able to integrate it into their everyday lives.

Now, a handful of European innovation bodies are working with social readiness scales, which they say will provide a reality check for researchers and engineers who may be overly focused on what their innovations can do.

“How do we make sure that what we can develop from a technical point of view is also something that society wants?” asks René Damkjer, head of the Grand Solutions programme at Innovation Fund Denmark. “Is it something that society is ready to accept, or will it take ten years to implement?”

Ignoring these questions can have serious implications for the future of an innovation. “The deployment of technology projects is often hindered or delayed because of societal considerations,” said Marit Sprenkeling of TNO Vector, the Centre for Societal Innovation and Strategy at the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO).

These questions need to be asked early on. “We find that many social aspects are dealt with much too late in the development process,” Sprenkeling said. “Often the technologies are already at a very high TRL when the societal aspects start to be discussed.”

Innovation Fund Denmark’s interest in societal readiness is directly linked to its mandate from the Danish government to invest in technology, research and innovation that has impact, for example producing economic growth and new jobs. “That can only happen if there are buyers at the end of the process,” said Damkjer. “In order for us to take that into account, it needs to be part of the application evaluation process.”

In response, it developed a social readiness level (SRL) index that runs from SRL 1, of identifying the problem to be tackled by the technology and social readiness as an issue, to SRL 9, when the solution has been proven in a relevant social environment. Internally, the SRL score plays a role in project prioritisation for the Grand Solutions programme.

This supports projects that promise to address societal challenges and can also create societal or economic value in Denmark. Companies, research institutions and public institutions can apply, with awards typically going to consortia involving several partners.

“When we go our board of directors and say you have to choose this project over that project, we need the SRL index in order to make the argument that the projects we’ve selected are closer to being implemented,” said Damkjer.

Putting social readiness on the research agenda

But the more important reason for using SRLs is to make sure that the teams behind the projects take account of societal readiness in the first place. “People have to address societal readiness in the application process, they cannot skip it,” Damkjer said. “And it is not just words, they have to put a number on it and justify that number. So, we are trying quite hard to make people think about this.”

This has not always been easy for applicants to understand. A scale similar to TRLs was chosen in the hope that this would be easier for scientists and engineers to get to grips with, but this tempts some applicants to see them as the same.

“Sometimes they think of the SRL as the TRL in disguise, and they give the same numbers. But when you ask why they’ve chosen those numbers, they can’t explain it,” said Damkjer. “So, it’s not well understood, and we get a lot of complaints from researchers asking how they should deal with this.”

The answer may be to consult colleagues in social sciences. “We want the technologists to work with the social sciences and humanities, because this will help them understand societal readiness,” said Damkjer. “At the end of the day, we want to see more multidisciplinary projects.”

Most applications to the Grand Solutions programme have a university in the consortium, so the expertise is there if the cultural differences between faculties can be overcome and relevant people brought on board. Equally, the issue can be addressed by industry partners, assuming that sales and marketing are involved, and not just the R&D departments.

When it comes to project evaluation, applications where the SRL is not well understood will be marked down and might not get funding. A project with a low SRL might also fare badly if the team behind it doesn’t have a plan for increasing it. Positive measures might include a work package to engage with consumers, for example about their willingness eat novel foods, or by planning to modify the technology, for example by taking steps to make artificial intelligence systems more transparent or increasing safeguards.

What is less clear at this stage is how SRL assessments play out once a technology or innovation reaches the market. The Innovation Fund is only now seeing projects that have used its SRL scale reach completion, and it will be watching closely to see what happens next.

“Looking ahead three or five years, it would be interesting to see if there is a correlation between projects that have worked with SRLs and those that have achieved good impact,” said Damkjer. However, it is also clear that social attitudes are a moving target, and may change before a technology reaches the market. “The important thing is to see whether or not people have thought about it.”

Broadening the social spectrum

TNO has taken a broader approach to social readiness, developing a system of societal embeddedness levels (SELs) for application by its project teams. These include the public and stakeholder perceptions commonly covered by SRLs, but also take in factors such as the interaction of the technology with the environment, policy and regulatory considerations, and market and financial resource availability.

“We find that all these societal aspects interact with each other, and we wanted to put them all in one methodology,” said Sprenkeling. This methodology was developed initially for energy technologies, such as hydrogen energy, and carbon capture and storage, but it is intended to be applicable in other areas. “The methodology is technology agnostic, although the requirements are different for different technologies or cultural contexts.”

The four SELs are linked to the nine TRLs, so that project teams know what social considerations they should be working on as their technology advances. “Ideally these develop in parallel, so when they start technology development, in a very low TRL, they would also start looking at the requirements for societal embeddedness in SEL 1,” Sprenkeling said. “In reality, however, there is often a gap, and we often see that a technology is already in a very high TRL, but still in a very low SEL.”

In this case, teams have to go back and put in additional effort to raise the SEL. This might involve looking at a range of issues, or just one or two that have been neglected. For example, a project might be ahead on market aspects if it is entering a well-developed sector, but it might be lagging on public acceptance. That might be the case in solar power, a mature market where acceptance can vary greatly depending on the setting or community in which it is to be deployed.

At the moment, TNO Vector is applying and further developing the SELs in research and innovation projects, but as the methodology becomes better understood it should be possible to hand over to the project teams. However, it is always likely to be a collaborative process.

“The methodology is most helpful when it is used in an interdisciplinary setting,” Sprenkeling said. “The project developer could be leading the process, but within that process collaboration will always be necessary.”

It is also likely that working on SELs will be a continuous process for technology developers. “When you are at TRL 8 you do not really expect to go back, because technology is very controllable. But society is not, and that is something that should be integrated in the further development of the technology,” Sprenkeling said. The goal is to anticipate challenges. “The SELs are not intended to change society, but to assist in how to adapt the technology to the societal context in which it will be developed and applied.”

This means that SELs should continue to be useful as technology moves closer to the market. “As you move to commercialisation and broader deployment in a societal context, new factors can come up that you have not faced in the demonstration phase,” Sprenkeling said. “When you are deploying a technology in different communities, other stakeholder perspectives and local values can play a role, so the SELs remain relevant.”

SELs may also prove useful to investors. “There are many examples of projects that are delayed or cancelled due to societal aspects, so I can imagine that it would be very useful for investors to have a grip on the societal embeddedness of a project in which they are planning to invest,” she said.

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem…

- There has been a resurgence of interest in patenting offshore wind energy technologies, according to data assembled by the European Patent Office and the International Renewable Energy Agency. A surge in global patent filings from 2006 to 2012 was followed by stagnation until 2017, when activity picked up again. The most patented technologies involve floating foundations, transportation equipment, and the installation and erection of turbines. But there is also strong interest in combining offshore wind and electrolysers to produce hydrogen, with the number of international patent families in this area doubling between 2020 and 2021, a trend that appears to continue into 2022.

- EIT Food, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology’s food community, is expanding its Food Accelerator Network to include a new hub in Brazil. The aim is to support agrifood technology start-ups from across Latin America that want to accelerate in the EU region. The Brazil hub will have a particular focus on food bioprocessing, next generation plant-sourced solutions, and sustainable food packaging. Meanwhile, European start-ups in the network will have an entrée into the Latin American market.

- The European Investment Bank is providing Italian start-up Xnext with a €20 million venture debt loan to support further R&D on its X-ray inspection system. Currently used for quality control in the food processing sector, the system is also expected to applications in the textile and pharmaceutical industries. Xnext claims its technology offers superior detection of low-density foreign bodies, reducing the risk of food product recalls and limiting the environmental impact caused by the waste of resources.

- VectorY, a Dutch start-up founded in 2020 by the venture capital firm Forbion, has raised €129 million in series A financing to advance its vectorised antibodies in treating neurodegenerative diseases. The money will support clinical development of a treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosi and preclinical development of other programmes using the company’s technology platform. The round was led by EQT Life Sciences and Forbion.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.