Experts debate what Europe should do to close the growing global data divide

When it comes to capitalising on artificial intelligence and data analytics, some countries and companies are streaking ahead of others. That was the view of some of the speakers participating in an online Science|Business workshop exploring the Great Global Data Divide.

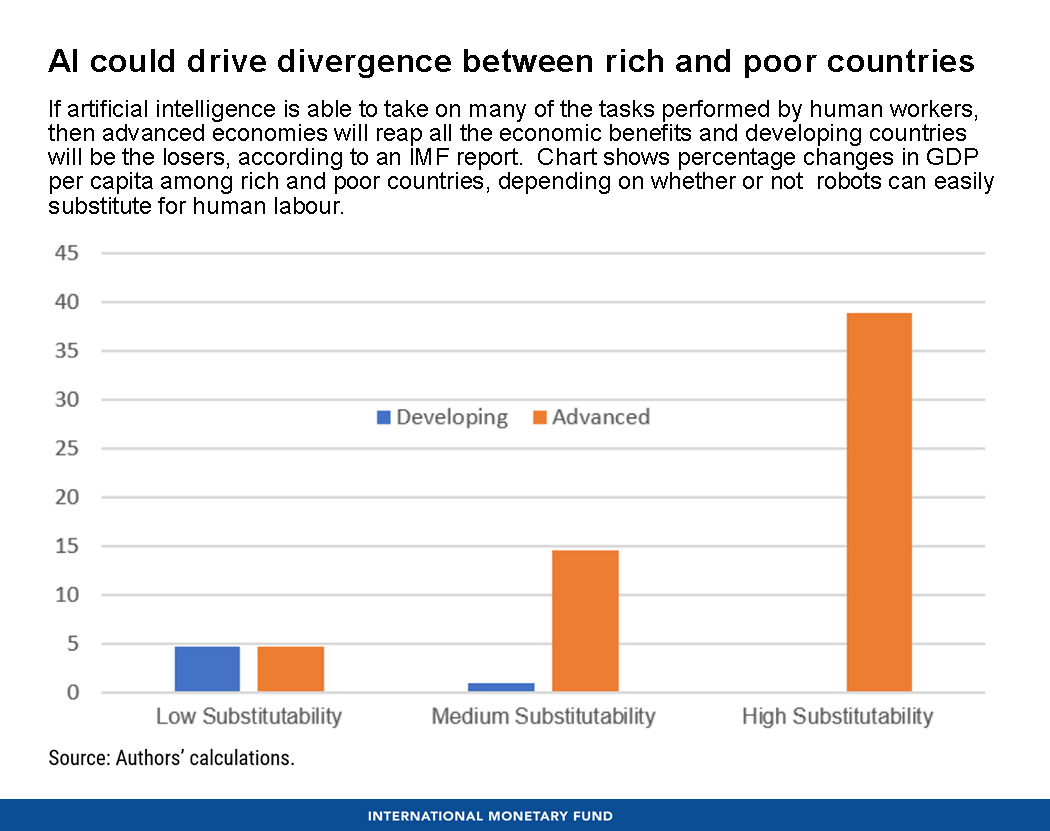

Describing the “worrisome” network effects that are concentrating artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities in the hands of a few, Nicolas van Zeebroeck, professor of digital economics and strategy at the Université libre de Bruxelles, said: “It's quite clear that the imbalances you see growing in terms of profit accumulation, but also in terms of skills and data concentration, for instance, are a potential source of instability at every level.” In a similar vein, research by the International Monetary Fund has warned of “a great divergence” driven by AI and robotics (see chart).

For van Zeebroeck, the “two animals” that policymakers need to tame are “insufficient labour and social mobility within and across countries, and growing barriers to entry and innovation due to the accumulation of data and skills” in a few hands. He noted that the development of effective AI requires a combination of the right data, the right skills, the right culture, the right infrastructure and the right software. “You need the full ecosystem in place and that is what Europe and the developing countries need to invest in,” he added.

But how much should they invest? While it is clear that both countries and companies need to capture data and put it to work, assigning a monetary value to this activity is very difficult. “Many economists, including those of the OECD, are trying to understand how to value [data] and how to understand its worth,” noted Audrey Plonk, head of the Digital Economy Policy Division, Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation of the OECD. “And that's a tricky, tricky puzzle.”

In terms of patent applications and research collaboration, “we see the United States and China very far ahead of a lot of other countries, including the EU, if you take it as a bloc” Plonk added. “We're releasing some new data in the next few weeks on [venture capital] investments, and in there, you'll see the United States is way, way ahead of even China and everywhere else.” However, she cautioned that such metrics only tell part of the story and don’t necessarily imply a widening gap.

In addition to public sector investment in research and development and skills, a coherent national strategy can be important. “We've seen a proliferation of national AI strategies in the last two years,” Plonk said. “The minute that the government puts some high level targets in place […] it inspires a whole bunch of activity, both in the private sector and in the public sector. ”

Counting the cost of connectivity

For the global south, one of the biggest obstacles could be the cost of digital infrastructure. There is a “data divide based simply on the lack of affordable connectivity,” explained Cathrin Stöver, chief communications officer of GÉANT, which connects European scientists to each other and to their counterparts elsewhere in the world. “And I have to stress that this is not a lack of cables anymore. It used to be, but it is no longer,” she added.

Although Africa is one of the best-connected continents in the world (in terms of the cables that serve it), bandwidth between African cities can cost €60 per megabit per month, compared with just two Euro cents between European cities, according to GÉANT. “In parts of Africa, connectivity is not just a little bit more expensive. It is 3,000 times more expensive,” noted Stöver. “And that, from our perspective, is one of the major drivers of the continuing digital divide.”

During the pandemic, the lack of affordable connectivity meant that education came to a complete halt in much of the global south, Stöver noted. “This is absolutely terrible for the development of these economies. And I think that has shaken a lot of stakeholders.” To help GÉANT bring down the cost of connectivity, Stöver called on the European Commission to establish more programmes that include a regulatory dialogue, alongside investments in infrastructure. At the same time, more activities need to be “driven by the global south” to find solutions that work and not simply “copy and paste activities from Europe or the US because they work in our economies,” she added.

Towards a more equitable economy

A growing gulf between “data haves” and “data have-nots” is also apparent within different sectors of the economy. Outlining the findings of a study based on 50 in-depth interviews with organisations in Europe, Atia Cortés, post-doctoral researcher at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, said there is “a different maturity in the levels of AI being implemented and embedded in the business models and this was independent of the business sector.” She highlighted “a big difference” between large companies, SMEs and research centres reflecting differences in their financial and human resources.

Cortés called on Europe to develop strategies to boost AI uptake “at all levels,” while also putting in place some mechanisms to ensure that local communities retain more of the value accruing from data that they generate. “The main challenge that governments have, especially here in Europe, it how to retain the talent that is created here, both in academia and in the private sector, especially in SMEs, which is one of the basis of our economy,” Cortés added.

Indeed, the vital role of skills and education was a recurring theme of the webinar. As AI permeates many aspects of daily life, it may be necessary to ensure that anyone in a position of authority (regardless of their area of expertise) understands AI. Teresa Scantamburlo of the European Centre for Living Technology, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, highlighted how several countries in Northern Europe have introduced AI into a wide range of university courses, including the humanities, while also expanding computer engineering courses to consider the ethical and societal implications of AI.

Although Scantamburlo argued that governments can play a pivotal role in ensuring AI is ethical and trustworthy, she also stressed the need to “have some other independent organisations looking at the work that governments do.” In particular, Scantamburlo flagged “the spectre of increasing surveillance and also opacity of bureaucracy and public services” as issues that need to be monitored by independent organisations.

Can Europe influence the rest of the world?

A key pillar of the EU’s digital strategy is to develop a “trustworthy” approach to AI, distinct from the more freewheeling approach taken by the U.S. and the state-centric strategy pursued by China. At the same time, the EU is encouraging greater data sharing both within Europe and globally.

Microsoft, which has been running a global open data campaign for 18 months, regards Europe’s strategy as broadly consistent with its view that disseminating data more widely is beneficial. While welcoming the EU’s new common data spaces (initiatives to pool public and private sector data for mutual benefit), Jeremy Rollison, senior director, EU government affairs at Microsoft, stressed the need to get the balance right between advancing European companies and research and ensuring they have access to the best tools. “What kind of direction are we going to take when it comes to intellectual property in this space?” he added. “How do we create a framework that's still incentivizes data collection, data curation and fostering access to that data?”

Rollison stressed that Europe needs to carefully measure the impact of its initiatives in terms of “exactly how much data sharing do [they] create.” If it proves effective, Europe’s evolving AI and data regulatory framework could be very influential with third countries, just as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been widely emulated. “If the data sharing takes off and competitors in Europe are more comfortable being part of joint public-private initiatives or sharing data with each other that drives their global competitiveness, then I think you will see the rest of the world emulate that as much as possible,” he added.

Of course, there is also a risk that overly rigid regulation holds Europe back. The EU needs to make sure that the rules allow organisations to access the best talent, tools, technologies and platforms, Rollison stressed. “Open is a key word here, both in the context of data, and in the context of access to the talent, to the technologies, to the types of software.”

Winning hearts and minds

However, not everyone is comfortable with the concept of open data. Hilary Hanahoe, secretary general of the Research Data Alliance (RDA), acknowledged the “fear that people have around the word open”. She stressed that “open data is not necessarily free data.” Building on the observations of the other speakers, Hanahoe highlighted the need for trust, as well as skills and standards, to close the global data divide.

Noting the need to build trust across a global data sharing ecosystem, as well as between people and the technologies, she highlighted the importance of ensuring that people and communities in developing countries maintain control of their data. To that end, the RDA and the Global Indigenous Data Alliance have co-developed the CARE principles to guide the management of data. Designed to be complementary to the widely adopted FAIR principles (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable), the CARE principles call for “collective benefit, the authority to control, responsibility and ethics,” Hanahoe explained.

She described the CARE principles “as very, very pertinent to many of the global challenges, [such as] climate, population health and urban health.” Indeed, several workshop participants noted that the pandemic has underlined the need for greater global co-operation and data sharing to address the many threats that span international borders, such as infectious diseases, climate change and demographic shifts.

While calling for action to reduce the digital divide, Hanahoe stressed that policymakers shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that “a digital revolution is the upside of this – there is a lot of opportunity.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.