The head of Europe’s defence R&D agency says mindsets have to change. There are plans to launch a €13B EU common defence research programme in 2021 and academics and small companies need to overcome their reluctance to working in this field

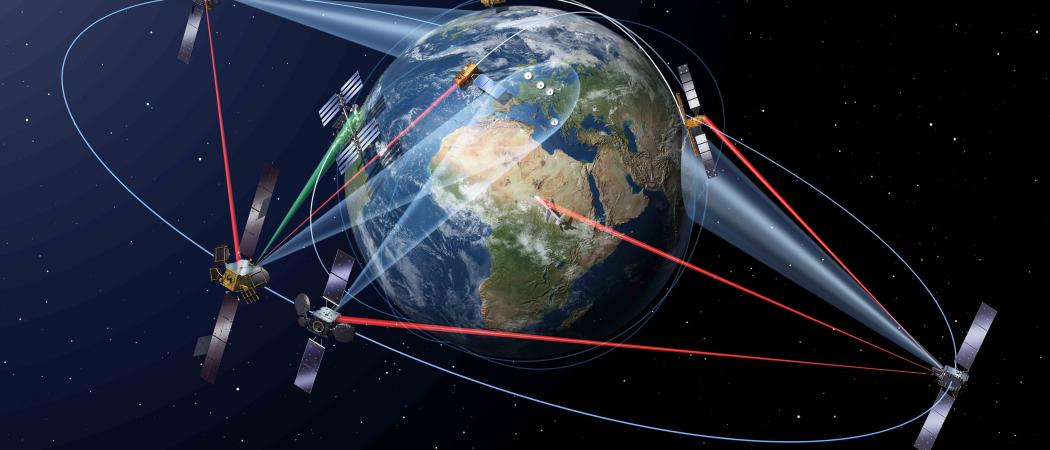

An illustration of the SpaceDataHighway, a satellite transmission system for critical defence data, developed by Airbus in partnership with the European Space Agency. Photo: Airbus

The EU is making more money available for defence research but academics and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are shying away from getting involved in military projects with the defence industry.

The boost funding from 2021, when the EU launches is first defence R&D programme, will not have a positive impact unless all member states agree on common security needs and convince research institutes and innovative SMEs to get involved and cooperate with Europe’s large defence companies on military projects, delegates at a conference held last week in Bucharest agreed.

The conference was organised by the European Defence Agency and the Romanian presidency of the EU Council as a forum for the EU to cement the push for common defence systems, based on home grown research and technology.

That requires persuasion, given how member states are fragmented across different geopolitical allegiances, and in view of the wariness of European researchers and SMEs of involvement in the defence industry.

Mindsets have to be changed for people to see working in defence R&D as a “noble task”, said Denis Roger, director for research, technology and innovation at the EDA. “There is still some reluctance to work for the military industrial complex,” Roger said.

A realignment in European defence, backed by R&D funding from Brussels, could give a boost to Europe’s defence industry. Companies like Airbus and Thales are already involved, but it is difficult to convince SMEs to collaborate in defence projects.

Christian Bréant, vice president and director of advanced studies at Thales, which builds electrical systems for the aerospace and defence industries, said EU R&D funding is needed if Europe is to attain “strategic autonomy”. Currently, he said, the EU is “dependent on other countries.”

The defence division at Airbus is applying technologies from the civilian sector to build defence capabilities. “We depend on a strong SME community and on high-class academia,” said Christian Munzinger, research and technology director at Airbus Defence & Space. But “finding the right partners is easier in civilian research,” Munzinger said.

Common defence market

Defence is one of the few major policy areas left uncovered by the EU and the reluctance to start working on a common defence research strategy reflects the fragmentation across different geopolitical allegiances. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, headed by the US, is the leading alliance on which Europe’s common defence strategy depends, however, Austria, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden are not members.

US President Donald Trump’s demands for European countries to contribute more funding and resources to NATO led Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Emmanuel Macron to call for the establishment of an European army to complement NATO. In a speech to the European Parliament last year, Merkel said the military alliances of old are no longer reliable. “The times that we could rely on others without reservation are over. We should work on the vision to one day create a true European army,” Merkel said.

Member states are also worried about potential cyberattacks and misinformation campaigns orchestrated by foreign actors in elections and referendums.

To address these issues, member states need to agree “a coherent approach” for defence, said EDA chief executive Jorge Domecq. “Investment in research and especially in collaborative research is a must to be able to deliver the defence capabilities for the future,” he said.

A funding maze

The European Commission has launched calls for defence research worth €25 million, which are part of a larger defence industry programme worth €500 million. The Commission’s larger ambition is to launch a €13 billion defence programme in 2021.

But figuring out how to navigate the maze of schemes the EU has put in place to spend the defence research money will not be an easy job. Stakeholders are worried about possible overlaps with national defence R&D funding and with funding for civilian research. But also – and perhaps more importantly – they are concerned about how to convince all member states to agree on a single strategy and play by the same rules.

“We don’t share results of research programmes enough, but this could be possible at EU level,” said Ralf Schnurr, research and technology director in the German federal ministry of defence. However, Schnurr warned EU defence R&D funding won’t work if it fails to “prove the direct link between research and armament.” In this case it will be difficult to ask for funding in the future.

The EU should make sure the final results of R&D investment “correspond to the need of our forces,” said Andrei Ignat, Romanian state secretary and chief of the department of armaments.

The EDA used the conference to showcase the panoply of funding instruments it has come up with to address those questions. These revolve around EDA’s Overarching Research Agenda (OSRA), a strategy approved by all member states in January to help the EU identify common research priorities that match the needs of Europe’s armed forces.

The goal is to “ensure redundancy is minimised and complementarity is maximised,” said Roger.

OSRA is also intended as the framework on which member states agree which civilian technologies are relevant for defence, to move faster towards a self sustainable defence industry in the EU. “We need to recognise as early as possible which technologies are relevant for defence,” said Schnurr.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.