There is broad support for EU Chips Act’s ambition of reducing reliance on imports of semiconductors, but experts are questioning the means and goals

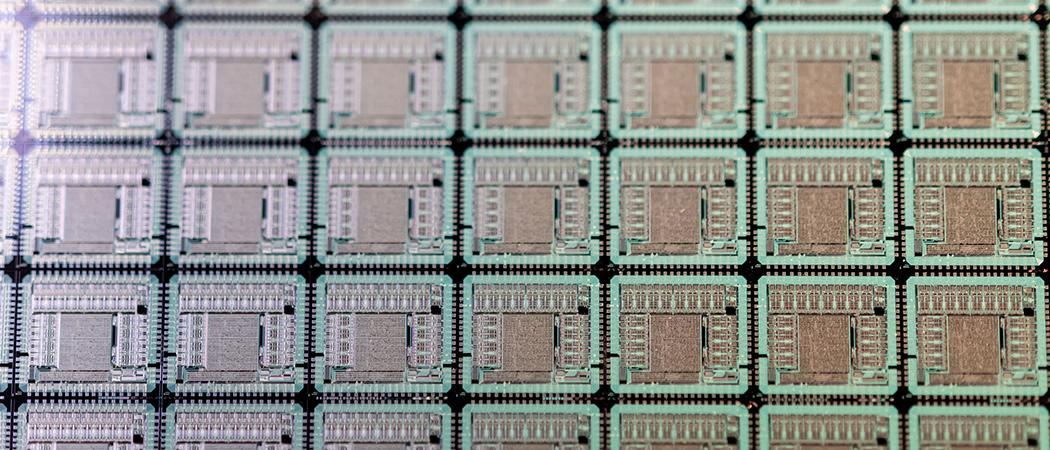

Close up on the wafers. Photo: European Union, Lukas Barth.

The European Commission put forward the EU Chips Act as a way to address the shortages of semiconductors that plagued European industry following the supply chain disruption caused by the pandemic, and in recognition of Europe’s over-reliance on imports of these critical components.

The Commission aims to levy billions of euros to scale-up chip production facilities and to induce the industry to focus on the development and manufacture of the most high-end, specialist semiconductors, rather than commodity products.

While there is a broad consensus that the EU needed to act, not everyone agrees on the means and goals. Three main bones of contention are whether there should be so much focus on incentivising manufacturing, if it is correct to focus on high-end chips, and – inevitably - if the budget is sufficient to achieve the targets.

As the Commission notes, semiconductor production is both knowledge and capital intensive. While the EU makes significant investments in both, that is not sufficient to address the scale of the challenge in the sector. “A more comprehensive set of actions and financing schemes is needed,” the Commission says.

Public funding for the Chips Act will amount to €11 billion up to 2030. On the back of this, the Commission hopes to pull in a further €32 billion in private investment.

The €11 billion for R&D is actually money that has been redirected from other programmes such as Horizon Europe and Digital Europe and was already earmarked for projects related to semi-conductors.

In the view of Niclas Poitiers, researcher at the think tank Bruegel, the EU cannot compete with East Asia in semiconductor manufacturing, and rather than investing in production facilities the money would be better spent on R&D. That would allow the European industry to specialise in high value areas of the semiconductor chain, like design, Poitiers told Science|Business.

For Kjed van Wieringen, policy analyst at the European Parliamentary Research Service, a more realistic goal “would be to retain the strengths we have now.” Europe is a “front runner in research and [in] equipment manufacturing,” van Wieringen said. While the Chips Act recognises these strengths, there should be more attention paid to maintaining them.

Europe will have to “work hard to increase its relevance in the value chain,” Jan Frederick Slijkerman, economist at the Dutch financial services firm ING, wrote in reaction to the Commission’s plan.

“Europe plays a significant role in some R&D intensive fields, such as machinery and intellectual property,” Slijkerman said, referring for example to the Dutch company ASML as “world-leading”.

In addition, Europe has “strong fundamental research, with research centres such as Imec in Belgium. But, Slijkerman noted, “Europe is a relatively small player in design and manufacturing,” which is where “most of the value is added”.

Are the chips up or down?

On the issue of R&D and the Commission’s focus on high-end chips, critics have pointed out that the current demand from European industry is for low-end chips.

If the Commission really wants to focus on production, it should be on ramping up the manufacturing capacities on the lower-end, Poitiers said, such as semiconductors currently used in the automotive industry.

While that is a short term driver, it is also important to be able to innovate and keep up with developments, as chips in cars will also become smaller, van Wieringen said.

Jo De Boeck, chief strategy officer at the leading European research institute Inter-university Microelectronics Centre (Imec) told Science|Business it is important to help current chip producers to grow, but it is also necessary to look to the future and anticipate future needs.

“There is a demand for [high-end] chips in Europe”, and it takes time before these can be manufactured. With this act, Europe is building “a storm for innovation”, De Boeck said. It should not be a case of choosing between low-end and high-end chips. Both are needed in Europe and they actually go hand in hand.

Budget woes

The €43 billion the Commission hopes to pull into the sector would double the EU share of the semiconductor world market to 20% by 2030

As van Wieringen noted, to reach that target, not only would production need to be quadrupled, but also the work force, which will not be easy to do. Policy experts in the European Parliament are not sure the EU will actually be able to reach this goal as it seems a bit “overly ambitious” van Wieringen said.

And as Poitiers points out, a budget of €43 billion is very little money set against the cost of new chip fabrication plants. As the latest example, Franco Italian firm STMicroelectronics this week announced plans to build a new facility in Catania, which will cost €730 million. Of this, €292.5 million is coming from a grant from the Italian government.

But if invested in semiconductor R&D, €43 billion would be a significant sum.

De Boeck agrees the budget is quite limited, but thinks it is enough to get things rolling. And if the environment in Europe is favourable private investments could easily exceed the €43 billion target. However, De Boeck said, companies will be taking many aspects into account before deciding where to invest. Relatively high energy costs in Europe might be a barrier.

In some senses, Intel has already blown the Commission’s budget out of the water with its announcement in March of plans to invest an initial €17 billion into a semiconductor fab in Germany, a new R&D and design hub in France, and to invest in R&D, manufacturing and foundry services in Ireland, Italy, Poland and Spain.

Announcing the investment Pat Gelsinger, CEO of Intel, acknowledged the influence of the EU Chips Act, saying “[It] will empower private companies and governments to work together to drastically advance Europe’s position in the semiconductor sector.”

STMicroelectronics and Intel’s announcements of major investments in semiconductor manufacturing would appear to be endorsement of the Chips Act’s aim of supporting construction of first-of-a-kind facilities.

This allows member state governments to ignore EU state aid rules and provide public money to secure building of facilities in Europe.

To qualify, it is necessary to show that an equivalent facility does not already exist in Europe, according to a definition set out in the Chips Act; that the supported facility will not crowd out existing or committed private initiatives; and that the public support covers a maximum of 100% of a proven funding gap, that is, the minimum amount necessary to make sure such investments take place in Europe.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.