The pandemic has supercharged research, but also closed off teamwork between countries

COVID-19 has ignited the scientific community in ways that no other outbreak has before.

But while the research is hugely international in scope and consequence, as a practical matter most of it is still being carried out locally, within single institutions.

Since the beginning of the outbreak, research teams have involved fewer countries, according to Caroline Wagner, a science and policy researcher at the Ohio State University in Columbus.

Wagner’s findings complement a similar investigation, which discovered that the vast majority of research on COVID-19 so far has been authored within countries.

“It’s highly localised for the moment. There’s not a lot of bilateral or multi-country research going on,” said Daniel Hook, CEO of London-based Digital Science, which runs a scholarly search platform.

The number of multiple-author scientific papers with collaborators from more than one country is currently low.

“People are staying in their own institutions; we’re seeing much lower rates of inter-institutional collaboration than you’d expect,” Hook said.

He says there are practical – but also psychological – limits on COVID-19 collaboration.

A crisis timescale means, “People are preferentially connecting to people they’ve connected to before. In a stressful situation, people go to where they’re comfortable. As a researcher in a crisis, you lack the energy to engage with your full list of values, which include being open and engaging with the world. It translates into the results we see here.”

Global teamwork on COVID-19 has also been blocked by control measures: many countries went into shut down in March, closing off opportunities for new partnerships.

“Scientists face a trade-off on international collaborative activities around time and efficiency, and that trade-off changes dramatically during a time of urgency,” Wagner’s paper says.

Funding pipeline – half open, half closed

A step up from the researchers, to the government funding bodies, the picture is also mixed. While researchers themselves may be sticking close to home, major funders in Europe and North America have published many calls for COVID-19 grants that do indeed allow foreign partners at least a minor role in a local project – just as they normally do.

According to an analysis of 273 predominantly English-language calls on the Science|Business COVID-19 research funding opportunities database, almost half allow foreign participation in one way or another, in many cases with certain restrictions, such as not allowing foreign researchers to lead the projects.

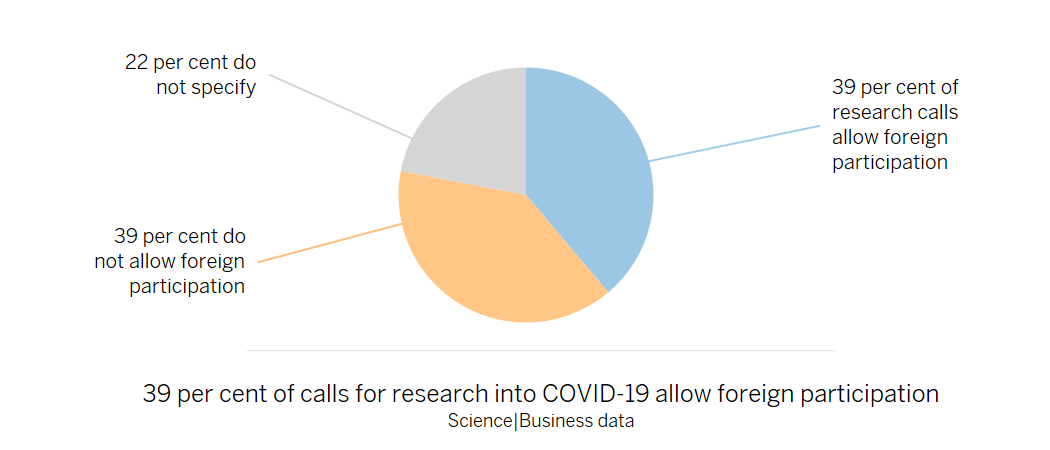

Of these 273 calls, 106, or 39 per cent, allow foreign participation, 107 do not (39 per cent), and 60 do not provide any indication whether they do or not (22 per cent).

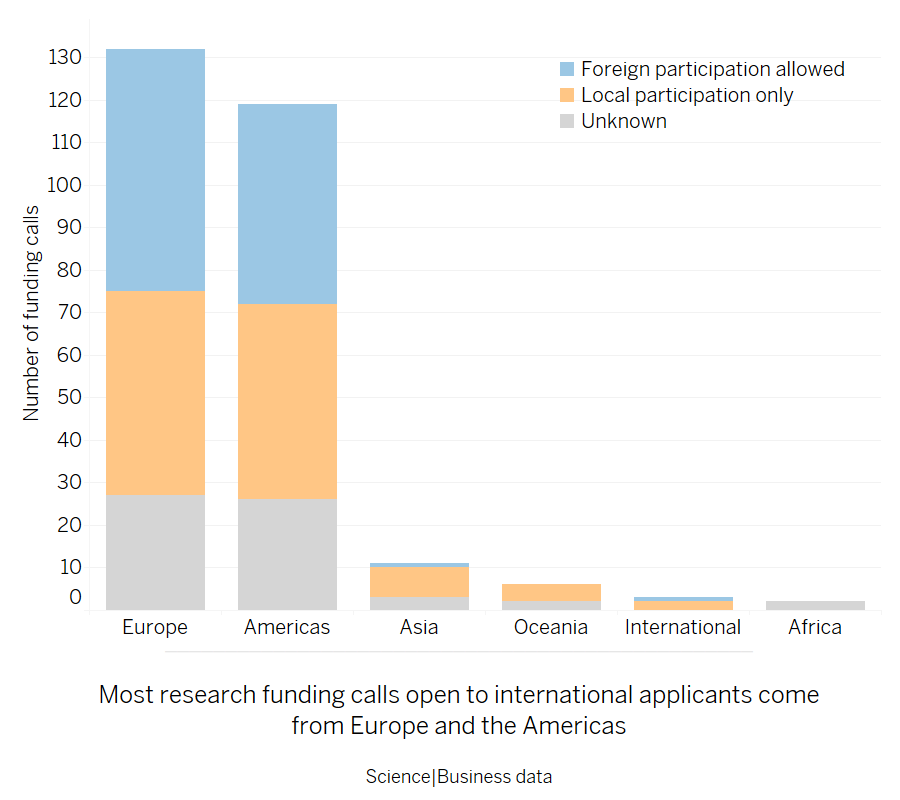

Overall, 48 per cent of these calls were published in Europe, 44 per cent in the Americas, mostly the US, and 8 per cent elsewhere.

Calls issued in Europe are slightly more likely to be open to the participation of foreign research partners, though the US is not far behind in this regard.

Big funding agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the US have come forward with significant COVID-19 grant money, but are maintaining their usual funding approach.

The 600 NSF grants issued in response to the pandemic will “result in findings that benefit the international community”, said NSF public affairs specialist Robert Margetta. In common with other grant fields, NSF money for COVID-19 only flows to US organisations, though partners from non-US institutes are permitted to participate with their own funding.

The 106 calls that allow foreign participation are distributed as follows: 57 from Europe, 47 from the Americas, and 2 from elsewhere. Of the 107 that do not allow foreign participation: 48 were issued in Europe, 46 from the Americas, and 13 from elsewhere. In the Americas, according to the Science|Business database, most of the calls for grant applications that are open to foreigners come from North America, with 37 from the US and six from Canada, while countries in the south tend to focus funding on their own researchers. Among emergency COVID grants issued so far in response to published calls, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research said 60 per cent of 99 funded projects include at least one international partner, and about 10 per cent have at least one EU partner.

“In my view, we are seeing what we would expect,” said Wagner. “I would expect that many of the basic research calls would be international, while public health and patient care might be more localised.”

Publications to date fall under three broad categories. “Patient care – these tend to be very national or local –, public health, also quite localised, and virology and immunology research, which tends to be more international in focus,” Wagner said.

‘Staggering’ growth

While multi-country teamwork is low for now, the worldwide collective funding drive on COVID-19 research exceeds anything witnessed before.

Vaccine research is being supercharged from international funds. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, based in Oslo, has funded a range of teams, from Brisbane, Australia, to Oxford UK.

The urgency of the pandemic has seen scientists drop a lot of the secrecy that is normal for research by openly sharing their findings and data.

Two online archives, medRxiv and bioRxiv, that share high-speed research before it has been reviewed and published in journals, report a deluge of coronavirus material from everywhere.

Several initiatives have opened up access to data on the virus, which would normally be restricted. Many journals, including the Oxford University Press, Taylor & Francis, Wiley, Elsevier and others, have made research findings and data relevant to the pandemic openly accessible to anyone in the world. Designs for medical devices such as ventilators, meanwhile, are being published and copied around the world.

The volume of output on COVID-19 is prodigious and growing.

“We’ve had 50,000 scholarly articles in five months. It’s just staggering. Research areas just do not come together that quickly,” Hook said.

For example, when deep learning, another hot discipline, started out, it took around seven and a half years to go from a few hundred papers a year to output of more than 11,000. In the case of COVID, the same volume has been reached in just four and a half months, said Hook.

It seems there are far more COVID-19 papers to come, with many of the funding calls still in the works, and research yet to get off the ground. According to data from Southampton University, global funding for COVID-19 research awarded up to June 10 was $951 million, far less than the total amount that has been pledged.

Even so, this amount, all awarded in the last six months, is almost double the total funding for all coronavirus research, including SARS and MERS, since 2000. In a very short time, COVID-19 research already accounts for roughly 70 per cent of all coronavirus studies published in the last 50 years, according to a study from the University of Sydney.

Consolidation of the elites

Alongside a reduction in the rate of global collaborations, the other big emerging pattern of the crisis is the consolidation of the strongest existing bilateral relationships.

“In the very earliest days, as one would expect, China took the lead at the world level, given their position in relationship to the virus. Then we see the China-US connection surge, and now there are many more countries participating at the global level,” Wagner said.

Despite the high political tension between China and the US, the rate of collaboration between the two elite science powers on COVID-19 is higher than for any two other countries in the world.

The crisis has sent Chinese-based authors in particular into hyperdrive, with Wagner and her team finding more papers in China in the first three months of 2020 than the number of articles produced by Chinese-based authors in the entire previous 24 months.

China enjoys the lion’s share of citations on COVID-19, but US and European institutions have gradually increased their publication rate.

Three to four major centres of research are emerging, according to Digital Science, covering an extended area of Wuhan, Beijing and Shanghai in China; Italy and the UK, the two hardest hit countries in Europe; the US’s east coast research corridor including Boston and New York; and finally, “a lighter focus” from the Californian institutions on the west coast.

Editor’s note: This article was corrected 19 June with additional information on the openness of Canadian calls to international partners.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.