Phages that kill bacteria are seen as a possible solution to the waning power of antibiotics. But research funding is lacking and existing routes to approval and commercialisation are not suitable for these therapies, say UK MPs

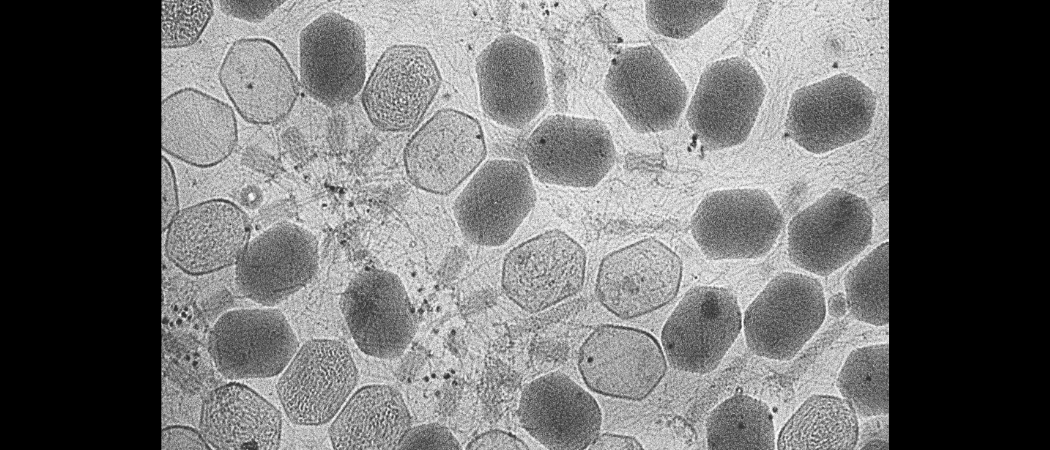

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria and are seen as potentially important in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. Photo: ZEISS Microscopy / Flickr

Bacteriophages that kill bacteria are potentially an important weapon in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, but their development as regulatory approved therapies is being underfunded and stifled by existing rules, according to a report by MPs on the UK Science, Innovation and Technology Committee.

Although the discovery and therapeutic use of bacteriophages dates to the beginning of the 20th century, the technology was largely overtaken by the arrival of broad-spectrum antibiotics. There is evidence of clinical efficacy from the former Soviet Union, in particular Georgia, and from India, where the use of phages has lived on.

Now, with traditional antibiotics dwindling in effectiveness as bacteria evolve, the rest of the world has turned its attention to phages as a possible solution to the slow-burning antimicrobial resistance crisis the World Heath Organisation fears could cause 10 million deaths a year by mid-century.

“The further development of phage therapies faces significant challenges that will need to be overcome if their potential is to be fully realised,” the report says.

Outside Russia and Georgia, phages are generally only available on a compassionate use basis as a last, experimental resort in a handful of clinics and when antibiotics have failed.

Even this one-off use is difficult because of restrictions on the use of medicines that are not produced in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), global guidelines designed make sure drugs meet high quality and safety standards.

High set-up costs, and uncertain commercial returns, mean that producing phage treatments to GMP standards is rare. Only Slovenia, Portugal, Norway and the US have phage GMP facilities.

To get around this bottleneck, the MPs suggest the government should invest in a small-scale or shared manufacturing facility to help produce phage therapies to GMP standards.

Phage therapies, if proven, are also likely to be more personalised than existing drugs, combining a cocktail of different phages and existing antibiotics tailored to an individual patient’s infection.

GMP rules for these personalised phage therapies therefore needs to be “flexible” the MPs say. One model is the way in which flu vaccines are updated each year to tackle new strains without needing a full new authorisation.

The MPs also want the UK to adopt hospital exemption rules that exist in Belgium and France, which allow scientists to culture individualised phage therapies so long as they follow certain quality control standards, albeit far less onerous than required by GMP rules.

This could allow greater use of individualised phage therapies, short of the mass production of generic treatments under GMP rules.

Clinical trial data

Despite the excitement over the potential of phages, the evidence for their effectiveness is still “mixed”, the MPs report.

“The field is still in its infancy, lacking significant randomised controlled trials of sufficient scale and repeatability, with most trials currently phase I and II,” said Francis Hassard, a public health lecturer at Cranfield University, commenting on the report. “The optimism associated with phage therapy should be tempered with a call for more rigorous translational scientific research to affirm both efficacy and safety of phage therapy.”

However, clinical trials have begun to strengthen the evidence base, the MPs say, including an EU-funded study Phagoburn, which worked on a phage product containing anti-Escherichia coli and anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages for combatting infections in burns patients.

Globally, 45 phage trials are ongoing, according to clinicaltrials.gov, the US government website where researchers are required to register clinical studies. Horizon Europe is currently funding 15 projects that involve phages.

But several obstacles remain. In the UK, there is a catch-22 situation, where phage treatments to be tested in clinical trials must be produced to GMP standards, but the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency requires clinical trial evidence of effectiveness to grant GMP status. “This impasse is stalling the development of phages in the UK,” the report says.

Another is that phage therapies may be too personalised to easily allow large-scale clinical trials. If a phage treatment involves a mix of phage types and other drugs, specific to the patient and infection, this makes it hard to run double blind, placebo-controlled trials, the MPs point out.

“Our evidence suggests that current regulations for clinical trials and the manufacturing of medicines are unlikely to be effective for phages as they are for other drugs or antibiotics,” they said.

Finally, there’s also a lack of public research funding into phages, at least in the UK, say the MPs. Pharmaceutical companies are also unwilling to invest, in part because patenting phages, which exist in nature, could be tricky, although genetically engineered phages might be more easily patented.

“Because phages have had relatively limited recent research funding from public sources, we recommend that the government reviews the status of phages within its plans to tackle antimicrobial resistance,” the report says.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.