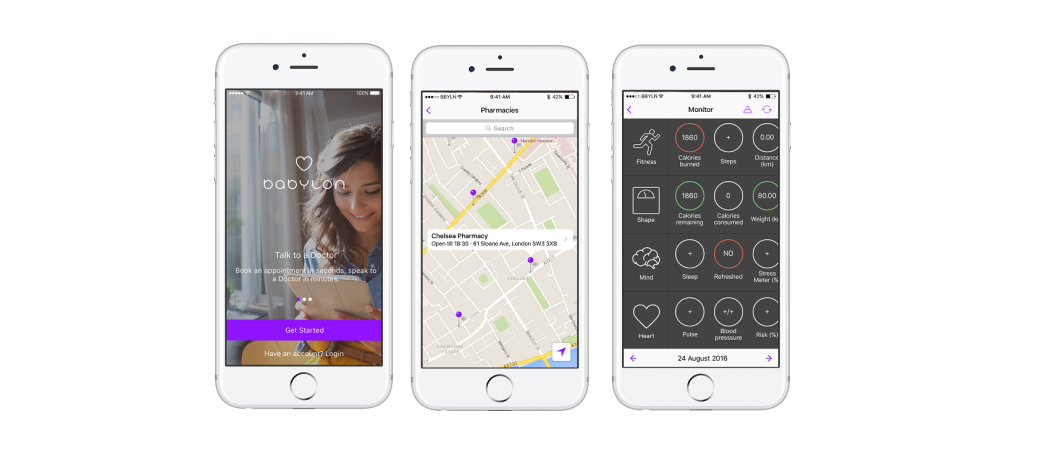

Babylon Health, a smartphone app powered by artificial intelligence, is making online diagnoses and has cut waiting times from two weeks to two hours – with the added convenience of remote consultations

A smartphone app introduced on a pilot basis in November is mining health data to make online diagnoses and has dramatically reduced the time patients in London wait for a consultation with a general practitioner (GP) by offering 24-hour access to a doctor via a video link.

Babylon Health, the company that developed the app says it means better access to GPs, improving health outcomes and reducing pressure on emergency services. The average waiting time for a virtual GP appointment is just over two hours for patients using its service GP at Hand, compared to a national average of approximately two weeks.

Babylon claims to have the widest reach of any AI diagnostic app. The company has raised more than €48 million to fund development of its system and in addition to a contract with the National Health Service (NHS) to deliver services in London, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is supporting its implementation in Rwanda, in a move designed to illustrate how technology can improve access to healthcare in low income countries.

The company was founded by former investment banker Ali Parsa CEO, who believes artificial intelligence (AI) will become a routine feature of healthcare everywhere. “It will soon be seen as ignorant, negligent and maybe even criminal to diagnose disease without using AI,” said Parsa.

If all patients had access to the Babylon system, outcomes would be less dependent on medical opinion and standards would rise for all, he said.

Show me where it hurts

The Babylon app collects details of a patient’s symptoms, which it then compares with millions of data points from other patients and research papers, to make a diagnosis and offer treatment advice.

Patients can touch an on-screen diagram of the human body to show where they feel pain, rate the severity of symptoms, and explain how long they have felt this way. Using this and the patient’s medical history, the app then suggests anything from an urgent hospital visit to resting at home.

The system can connect patients to a doctor by video if they want to speak to a human expert. Consultations are shorter than a typical visit to the clinic as the doctor is able to access the information patients have given the app, in advance of talking to them.

Where a prescription is needed, this is sent electronically. Medicines can be delivered or collected at a nearby pharmacy.

Individuals can subscribe to the app privately and some insurers provide it to their customers. However, the big breakthrough and most intense scrutiny has come since the NHS began encouraging patients to use the app.

While GP at Hand is still a pilot project linked to a handful of GP surgeries, many see it as the future of care. Charles Alessi, senior advisor at Public Health England, said the system offers a primary care service that, “Helps people stay healthy, as well as looking after them when they are sick”.

GP Howard Freeman said, “GP at Hand is a window onto what the NHS of the future will look like. When NHS GPs embrace Babylon technology to make life better for their patients, the sky is the limit.”

Replacing telephone hotline

In January 2017 the NHS started to roll out a Babylon-based app to patients in eight north London boroughs who might otherwise call the NHS’s 111 telephone helpline, which provides advice and helps to triage patients remotely.

“Forty per cent of patients who use the [Babylon] diagnostic service don’t go to the doctor,” said Parsa. “We also use predictive analytics to calculate the risk of developing disease or complications from diseases such as diabetes. We can help people to stay well.”

As the app continues to sign up thousands of patients per week and replace many tasks performed by doctors, there are questions about its accuracy and the impact on general practice.

Margaret McCartney, GP and a columnist in the British Medical Journal, said more evidence is needed to ensure the safety and accuracy of AI diagnostics.

There have also been accusations of cherry picking. Digital services are popular among younger, healthier people, leaving GPs to handle only older, sicker patients. Helen Stokes-Lampard, Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners has said this threatens the viability of general practice.

Babylon also found itself at the centre of controversy last year when it sought to block the release of a 2017 inspection by the UK’s Care Quality Commission (CQC), which found that in some areas the service, “Was not providing safe care in accordance with the relevant regulations.”

This was in contrast to a 2016 CQC report, which praised the service, declaring it safe and effective.

But while the 2017 report was broadly positive, it found fault with Babylon’s policies on sharing patient information with their registered GP and the use of prescribed medicines for conditions outside the terms of a drug’s license.

Babylon issued detailed responses to the report, arguing that the CQC frequently finds fault with digital and innovative health technologies. It noted that the criticisms related only to instances where Babylon was not the main care provider and did not apply to the GP at Hand service where Babylon effectively becomes the patient’s registered doctor.

The company challenged the CQC report in court to protect its reputation but succeeded only in attracting negative attention. Babylon eventually dropped its challenge, agreeing to pay the regulator’s legal costs of £11,000.

Digital disruption

One of the biggest questions raised by the UK’s embrace of digital technologies is what the effect will be on the jobs of healthcare professionals.

According to Babylon, AI is currently good enough to manage 80 per cent of primary care diseases as well as a doctor would. With the speed and accuracy of AI improving exponentially the technology will soon take over even more tasks, particularly in predicting and diagnosing illness, and identifying the best treatment option.

“By the end of the year, we will be an order of magnitude more accurate than any human doctor,” said Parsa. “No human brain can analyse this amount of data.”

But says Parsa, doctors will not be redundant. Rather they will play to their strengths and leave information-based tasks to machines. “We will make our doctors more human, and let computers do the computing,” he said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.