A new report says investment is at its lowest level in a decade, but a closer look shows that there are positive signs for Latvia’s emergent innovation landscape

Latvian Prime Minister Evika Silina. Photo: Latvian State Chancellery / Flickr

Key investors in Latvia are calling on the prime minister, Evika Silina, to focus on long-term planning and improving competitiveness after an assessment rated the country’s investment climate at its lowest point since studies began in 2015.

The 2023 edition of the Sentiment Index by the Foreign Investors’ Council in Latvia (FICIL) gave a score of 1.9 out of 5, a drop of 0.4 from the previous year and some way off the 2018 - 2021 average of 2.9.

The report is based on a survey and interviews with 66 senior executives from companies that are key investors in the country. For each annual report investors are asked to provide a message for the country’s prime minister. This year, they have called on Silina to “become bolder and more ambitious”. They want a long-term vision to improve Latvia’s competitiveness by increasing investment in innovation and infrastructure and thinking beyond the four-year election cycle.

They also want her to reduce bureaucratic barriers, favouritism towards state-owned companies and to solve the country’s labour shortages, saying “no people, no economy”.

The results of this year’s report are “worrying” for Latvia, FICIL’s executive director Tatjana Guzņajeva told Science|Business. But the findings should be seen in the context that the main reason for investors’ uncertainty is the war in Ukraine.

“I think investors are waiting for very clear signals of how exactly the government will ensure security defence mechanisms,” she said. “I would not take it as ‘no, we're not planning to invest’, it's more like, ‘I'm not sure what's going to happen so we better wait’.”

The report found that the number of businesses planning to continue investment in Latvia decreased from 79% in 2022 to 67% in 2023. While this is a sharp decline, in previous years the figure has bounced between 57% and 68%.

A spokesperson for Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA) said the war in Ukraine and deterioration of the overall economic situation in some of Latvia’s main export markets such as Germany and Scandinavia have led to a slowdown in investment flows, meaning some projects have been put on hold.

“However, there is still sufficient investor interest in developing new projects in sectors such as smart energy, hydrogen, metalworking, ICT,” the spokesperson said.

Foreign companies are still eager to work with Latvia and LIAA collaborated on 182 projects last year, with a potential revenue of €5 billion.

The impact of foreign investment

Reinis Āzis, who leads FICIL’s public sector reform working group and represents energy storage services company VTTI, said that in any case, the impact of foreign investment on Latvia’s innovation ecosystem is not necessarily high.

Most of the large companies responsible for funding start-ups or investing in training or research and development are long-established in the country and many are state-owned, meaning they provide a stable backdrop. On the other hand, foreign investors do contribute a large chunk of tax revenues that feed into the government’s budget for R&D and academia, so there is an indirect effect.

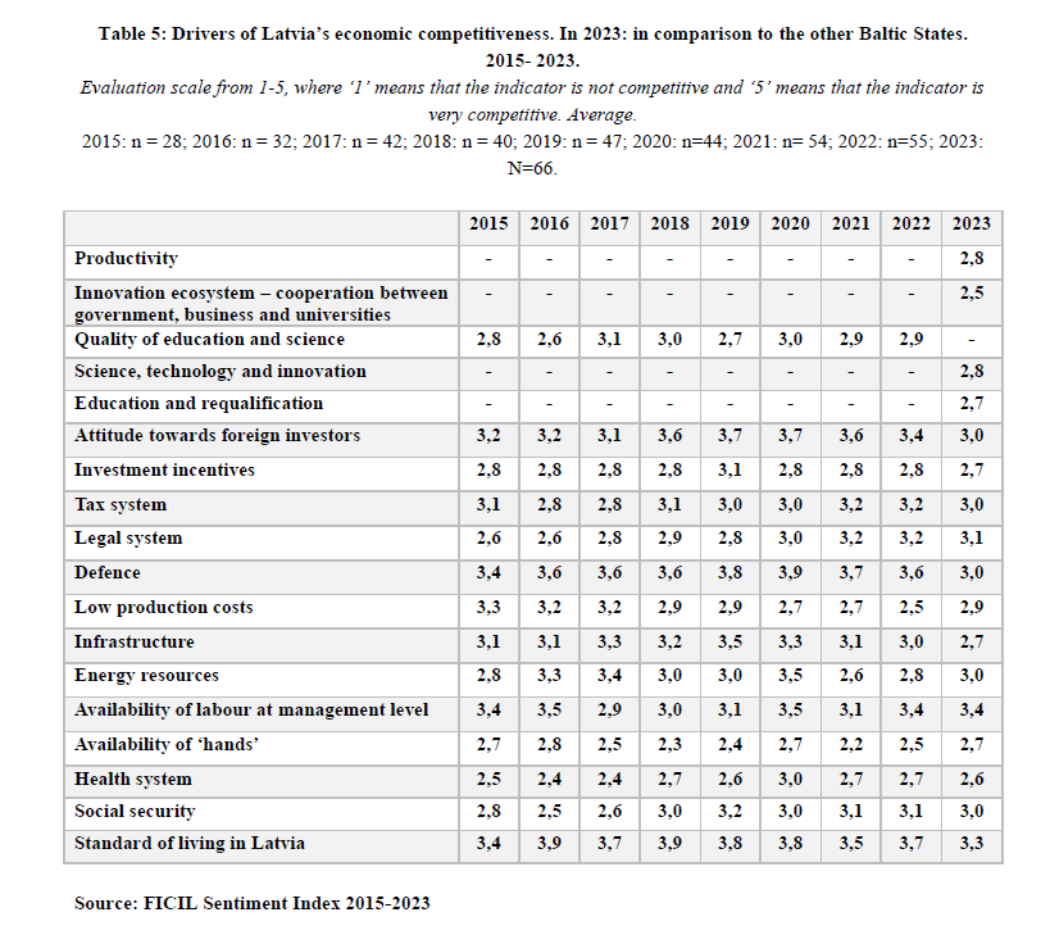

For investors, Latvia’s relatively weak innovation landscape in comparison to its Baltic neighbours Lithuania and Estonia is a reason behind the country’s lower competitiveness. The 2023 Sentiment Index is the first to ask investors for their thoughts on cooperation between government, business and universities in terms of driving Latvia’s economic competitiveness, and this measure received the lowest score of all the 17 areas, as shown in the table below.

This should serve as a message to the government, Guzņajeva said. “The results that reveal that Latvia’s innovation ecosystem is weaker than the other Baltic states will help to deliver a message to policymakers that something should be done.”

Caught between Tallinn and Vilnius

The three Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are often grouped together when assessing performance on a European level due to their geographic proximity and shared experience of having been occupied by the Soviet Union. When it comes to innovation, this often reflects badly on Latvia, which trails behind the other two.

Both Estonia and Lithuania are ranked as “moderated innovators” on the European Commission’s Innovation Scoreboard, while Latvia is in the weakest category of “emerging indicator” and is ranked third last in the EU ahead of just Romania and Bulgaria.

Stuck between its better performing Baltic neighbours, Latvia is often overlooked. “If someone is thinking about starting an IT company they would go to Estonia, if they’re thinking about fintech they might go to Vilnius where Revolut is based,” Āzis said. “In Latvia, we are still more known for less advanced production, more like secondary manufacturing processes.”

Olga Barreto Goncalves, CEO of the Latvian Startup Association, Startin.lv, said Riga often flies under the radar of investors and start-up founders.

“Even today we meet many investors who have heard of Latvia but never been here, never spoken to a Latvian start-up, so their confidence level and trust in our ecosystem is close to none,” she told Science|Business. “This is something for us to work on, for sure.”

In 2023 the investment in Latvian start-ups dropped dramatically compared to previous years, but this trend was seen across Europe and globally.

Goncalves is unconcerned. “It is a general consensus that this decrease should be attributed to the fact that the world-wide venture capital market slowed down due to COVID-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” she said.

“It is also believed that the ‘VC winter’ has passed and that in 2024/25 the snow will melt and investments will rise again. Estonia is already showing recovery signs. Latvia - not yet, but it is expected.”

Steady improvements

The country is making strides at improving its innovation ecosystem and is starting to narrow its focus to key industries such as IT, green technology, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. In 2022 the government set up the Innovation and Research Management Council (IRMC), bringing together the Ministry of Economics and the Ministry of Education and Science with the LIAA and the Latvian Council of Science.

The goal is to offer a higher level of coordination to the country’s R&I landscape and more broadly increase the competitiveness of Latvia’s companies.

The government has also set the objective of doubling its companies’ investment in R&D and increasing public R&D spending to 1.5% of the overall GDP in the next few years, up from around 1%.

These steps are going in the right direction and the “right kind of road signs” have been put in place, Āzis said. The problem is the implementation, which is often “lagging behind”.

Āzis supports the government taking a more goal-orientated approach to its budgets and policies, a strategy the Ministry of Finance “seems ready to put in place”. This would add much more certainty and could help ease worries of foreign investors.

“If we could manage to roll out a very strong performance-based budgeting strategy backed by our strong data system, that would be an important milestone,” Āzis said.

People and paperwork

Two other areas highlighted by FICIL as putting off foreign investors is complex bureaucracy and a shortage of talented workers.

On the bureaucracy side, investors said the high administrative burden leads to a significantly increased workload for staff and higher business costs. “This creates a sense of uncertainty, discouraging further investments in Latvia,” the report says.

Latvia’s bureaucratic burden can in part be explained by its history. After it re-gained independence in the early 1990s, the country had a big aversion for anything resembling a centrally planned economy and eagerly embraced deregulation. Then, in the 2000s, in order to meet the requirements to join the EU, it backtracked and focused on regulation. This has created confusion in the system that investors can find difficult to navigate, Āzis said.

He admits weighty bureaucracy remains an issue for the country. “We still see some annoying practices like having to submit paperwork to five or six public entities because they do not share data between them,” he said.

But the story is not so simple. Latvia has one of the best ratings for digital public services for businesses in the EU, according to the Digital Economy and Society Index. While there are still issues to overcome, such as cross-ministerial communication, the country has made significant strides, Goncalves said.

“I'm not sure if it is really appreciated how we've come in terms of bureaucracy burden,” she said, highlighting Latvia’s e-signature system that allows companies to easily do business and administrative tasks online. “The way I see it, bureaucracy definitely remains annoying, but I don't think it is in the top three or top five major challenges.”

On labour shortages, the issues are broad. The country has the talent, Goncalves said, but needs more of it, and especially needs more STEM-focused disciplines taught at universities.

The country’s higher education sector is an area of concern. There are 52 higher education institutions in Latvia, 28 universities and 24 colleges. “For a country with less than two million [people] it is too much,” a recent report by EU analytics institute Integrin states.

Āzis and Guzņajeva both said that while the country’s school-level education is strong, there is a drop off in quality when it comes to higher education.

All this requires time to put right, but Guzņajeva is optimistic. “It’s been 30 years since we regained independence and I feel great progress has been achieved,” she said. “Of course we are constantly compared to either Estonia or Lithuania but I feel that we have our own story and I believe there is a big potential.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.