Leaders of giant radio telescope project look forward to a year of milestones, including signing a treaty to give SKA intergovernmental status, smoothing its funding outlook

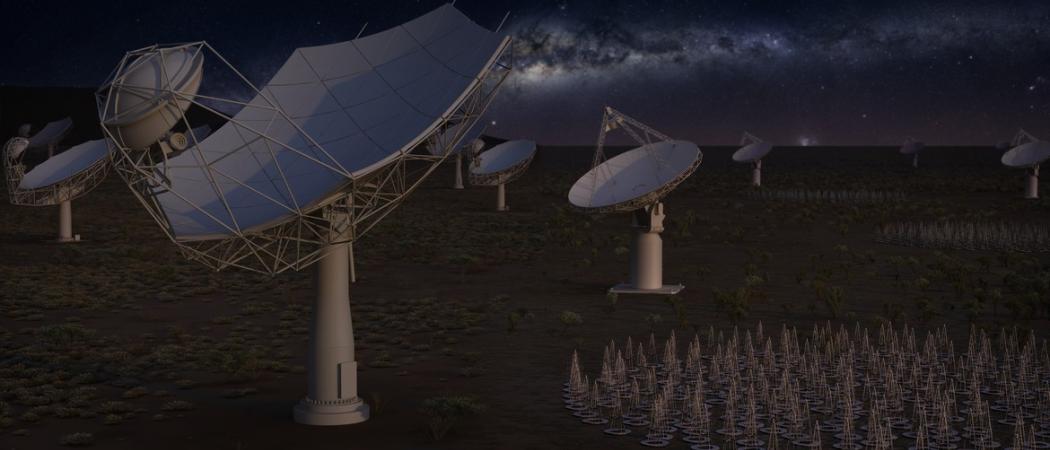

Photo: SKA Organisation

The Square Kilometre Array telescope project will secure its funding future this year, when it gains an intergovernmental status similar to that of another giant research structure, CERN, home of the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator.

Four EU countries, Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK - which houses SKA headquarters at Manchester University’s Jodrell Bank Observatory - are expected to sign a treaty in Rome in September. Canada, China, India and New Zealand are involved in negotiations and invited to sign the treaty too.

The EU signatories will be joined by South Africa and Australia, where the project’s dishes and antennas are located.

Portugal, while not currently a member of SKA, has expressed its intent to be one of the founding signatories, and has recently joined the process. The European Commission, which has provided some €30 million to the project to date, is not expected to gain a formal seat.

“The treaty should allow for a kinder tax system,” Phil Diamond, SKA director-general told Science|Business. He hopes the status means more countries can be persuaded to join the SKA project. “It will help with the predictability of funding, and ensure governance going forward,” he said.

When complete, sometime around 2030, SKA will be the largest radio telescope ever built, and 50 times more sensitive than current instruments. It will consist of around 2,000 radio dishes in Africa, together with up to one million antennas in Australia.

“We think Western Australia is one of the quietest spots in the world, so perfect for listening to space,” said Douglas Bock, director of the Australia Telescope National Facility.

The build-up is gradual, with the first phase of construction comprising 194 dishes in South Africa and around 130,000 antennas in Australia. While this approach is not without its problems, there is little alternative to having many countries collaborating on the project, said SKA South Africa project director, Rob Adam.

“Even if this occasionally means it’s slow, you see it can’t be done without scale. Even the US can’t go it alone always, as you can see with the [fusion] ITER project,” Adam said.

An array of 64-dishes called MeerKAT, a subset of SKA, is expected to go fully operational this July. “We want it to be the premier radio astronomy telescope in the world for at least five years,” said Adam.

To make space for the many satellites and antennas in South Africa, the project has purchased some 130,000 hectares of land belonging to 36 sprawling farms, supporting sheep, ostrich and springbok.

Save the Karoo, an advocacy group, has criticised this displacement of locals, as well as restrictions the project has put on radio frequencies in the area, which means mobile phones cannot be widely used around the site.

To make up for the disruption, SKA has sponsored a maths and science teacher at a secondary school in Carnarvon, a nearby town, and provided college bursaries for nine students.

“We also want to train local people to be technicians and [to do] maintenance,” said Adam. “It’s going to be more cost-effective than flying people in from Johannesburg and Cape Town.”

Data deluge

Astronomers estimate that SKA will eventually generate 35,000-DVDs-worth of data every second, or a new World Wide Web’s worth of data every day.

“It will be Facebook and Google combined,” said Diamond. Big supercomputer centres will be required to house the data. “We’re working with CERN to develop techniques to handle it,” he said.

Diamond, an astronomer before he was an administrator, says his personal wish is for the telescope to find and decipher signatures of biochemicals, such as amino acids, in space. “If we can show they’re pervasive, we’ll know that the conditions for life exist throughout the galaxy,” he said.

The original article said the EU contributed some €40 million to the SKA project. The actual figure is roughly €30 million. There was also a clarification made to the signatories of the SKA intergovernmental treaty. Corrections made on April 23.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.