An online sampling of opinion shows high passions in the scientific community about how to deal with Russian counterparts

Science|Business online survey results

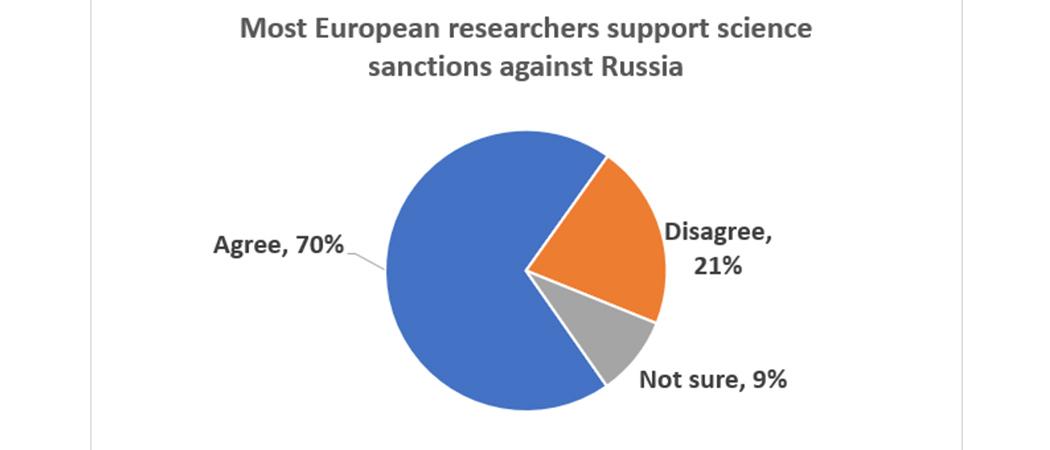

As the war in Ukraine drags on, more than two-thirds of European researchers who responded to a Science|Business survey say they support western sanctions on scientific relations with Russia.

Nearly 70% of the 240 individuals who identified themselves as researchers in the online survey said they agree that “scientific relations with Russia should be sanctioned in some manner.” Another 21% said they disagree, and the remaining 9% said they aren’t sure.

Not surprisingly, Ukrainian and Russian researchers who responded had firm views: of 78 researchers who identified themselves as Ukrainian nationals, all but six agreed with sanctions. And of 10 who said they are Russian, all but two disagreed. But even after factoring out those two nationalities, the results are largely similar: 62% of European researchers not from Ukraine or Russia said they agree with sanctions, 25% disagree, and 13% aren’t sure.

Likewise, in the broader population of 419 respondents – other professions, including corporate and government employees also responded – the tally was 69% in favour of sanctions, 22% opposed, and the remainder undecided.

The view of professional researchers on sanctions is especially important, as it is they who are most directly affected by the question. The survey, conducted anonymously and online from June 28, was intended as a sampling of that opinion and makes no claim of statistical significance for the results. But the pattern of responses – and the often forceful comments written into the survey form – demonstrates the passions provoked by the war in the otherwise apolitical scientific world.

Institutions v. individuals

Within days of Russia’s 24 February invasion, many western governments suspended official scientific collaborations with Russian state universities and institutions, and advised their own research organisations to do likewise. But most drew a distinction between dealings with official Russian organisations and individual Russian researchers: in most cases, individual, researcher-to-researcher, collaboration has been allowed to continue – although, without government funding for it any longer, that is often hard to maintain.

The survey results confirm that distinction between institutional and individual relations. When asked to distinguish between different kinds of sanctions, of the whole population of 419 respondents, 75% said they support curtailing scientific relations with “government-to-government partnerships and programmes involving Russian state institutions and universities.” And 66% support curtailing “Russian institutional participation in international research infrastructure."

But only 37% say there should be any effect on "partnerships or projects involving individual Russian researchers.” As for sharing research data, results or correspondence with Russian researchers, only 36% want that stopped. And 32% want to exclude Russian research results from international scientific journals and databases.

Strong views

In the anonymous comments, passions often ran high – both pro and con.

“Science has nothing to do with the sick ambitions of individual politicians,” wrote one French researcher opposed to sanctions. “It is ridiculous to impose any limits on scientific thought and its free exchange or expression.”

Likewise, wrote a Hungarian researcher: “I condemn the Russian aggression, but why does this question arise only in connection with Russia? Nobody asks similar questions when e.g. the US commits aggression against a sovereign state. Double standards.”

Some argued for the distinction between individual and institutional relations.

One Dutch researcher wrote: “Though governmental restrictions are called for when human rights are severely violated by an autocratic regime, individual scholarly relations with scholars who oppose the human rights violations should be maintained or perhaps even fostered, since that can help [in] freeing societies that are under autocratic rule.” In the same vein, a Greek researcher wrote: “There has to be a way to make sure that Russian researchers in fear of their regime are not isolated, even when they are not actively taking a stance against the war or their state.”

But the majority view, favouring sanctions, was strongly expressed.

Wrote a German researcher: “Free research needs free people and a free mindset! No collaboration with dictators, autocrats and nations not respecting humanity!” Agreed a French researcher: “All relations must be stopped with Russia because it is a terrorist state.”

And a Swedish researcher: “Don't be naive. Autocracies and mafia states should not be treated as countries ruled according to the principle of separation of powers.”

Russians and Ukrainian respondents had their views. A Russian researcher, opposed to sanctions, said: “Don't see any normal reason to manipulate scientific relations like politicians do, for reasons far from the real interests of science and people involved in it.” And a Ukrainian counterpart: “Russia is a terrorist state and Russians support the war. Because of them, Ukrainian scientists were forced to freeze their research, abandon their work, which they devoted many years to. Therefore, there should be no scientific contacts and connections with Russian researchers until they plead guilty and are punished for the horror inflicted on Ukrainians.”

Some reflection requested

Several researchers urged a considered view. Wrote an American: “Can we learn from history? What restrictions were placed on Nazi Germany during WWII? What worked and what did not work?” And a German researcher: “Sanctions should be limited in time and re-evaluated on a regular basis.”

Said a British researcher: “The Russian invasion of Ukraine shows the limits of European science diplomacy. We need to rethink and reassess what we are trying to do when we use science to foster relations with potentially hostile countries. Science can be harmed when it's used as a tool of diplomacy.”

And one Ukrainian researcher took a more nuanced approach: “Russia (as any other country) has talented scientists, cooperation with whom may be beneficial to the world. It is better to invite them to the countries that may benefit from cooperation with them rather than to cooperate with them while they stay in their home country. This will be different from cooperation with institutions or the government. However, an individual case-by-case approach needs to be implemented, because some of the scientists may be recruited by secret services for collecting scientific information that is not available legally.”

This is the start of a two-part look at our survey results. Second installment coming November 3.